George Whitefield Preaching in Bolton, 1750

“Think with your heart, not your head.” This phrase, which is received as a cliché when heard by many today, defined a period in colonial history that has been labeled the “First Great Awakening.” This “Awakening,” was a direct response to the Enlightenment that had swept through Europe and challenged religion with science and reason. Throughout the first half of the eighteenth century, the thirteen colonies were lit ablaze by a philosophical battle between groups dubbed “Old Lights” and “New Lights,” who fought for the religious soul of the people. Fiery and passionate leaders like Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield revitalized religion in the colonies and provided the future revolutionary generation with a taste of greater equality and self-determination.

At the beginning of the 1720s, just prior to the Great Awakening’s commencement, the thirteen English colonies were very religiously divided. The majority of New Englanders belonged to congregational churches. In the Middle colonies, Quakers, Anglicans, Lutherans, Baptists, Presbyterians, the Dutch Reformed, and Congregational followers were the makeup. Southern colonies were mostly members of the Anglican Church, but there were also many Baptists, Presbyterians, and Quakers.

The push for a revitalization in religion and conversion that had seen a decline in this new age began in New Jersey and Pennsylvania among the Presbyterians. Their efforts included the establishment of a seminary to educate new clergymen to spread the gospel. That religious school, referred to as the “log college,” is better known today as Princeton University. The overall movement was not widespread outside the boundaries of the Middle Colonies, but the groundwork was laid for several larger-than-life personalities to take the helm and awaken the rest of the colonies.

Religious revivals began in Europe during the late seventeenth century in response to the beginning of the Enlightenment. Spreading to the colonies, the movement also challenged the formality of Congregational churches and the abuse of power and control that was being witnessed—a protest to monarchs who used the church to retain their authority as well. The colonial revival went further than Europe’s previously had, however, and shattered class lines, welcoming all, not just white men, to convert, participate, and worship. The movement quickly shifted from a secular effort to a national phenomenon largely in part due to Edwards, Whitefield, and others who garnered the public’s attention and respect.

Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758) was the first leader in the movement to earn the national spotlight. A Yale graduate and Northampton, Massachusetts, minister, his message was powerful, if not downright terrifying for many to hear: All men and women were born as sinners. If he or she did not accept Jesus Christ and seek salvation, then eternal fire and brimstone awaited them in Hell. Edwards’s interpretation manifested an angry God who did not judge kindly unless forgiveness was asked for. His message, and others’, would transcend denominational boundaries throughout the colonies to help form a unified identity among Protestants.

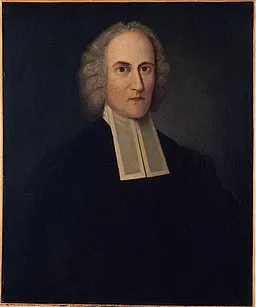

The most widely known leader of the revival movement was George Whitefield (1714-1770), an ordained Church of England minister from Britain. Arriving in Georgia in 1739, Whitefield embarked on multiple tours up and down the eastern seaboard, speaking in churches and outdoors, connecting independent denominations through one unifying message. His sermons were so powerful that tens of thousands of listeners would turn out to see and hear him. He was even successful in converting slaves and Native Americans. In one year, Whitefield covered some 5,000 miles and spoke over 350 times. His delivery style during his sermons was more theatrical than anyone had ever witnessed. His passion and raw energy excited his audiences and invoked an energy within them that reinvigorated their faith. He became one of, if not, the most famous men in the colonies. Benjamin Franklin, known to be a religious sceptic, even became enthralled with him and quickly befriended the reverend. Whitefield and the Awakening helped usher in a strong form of religious relevance to the contemporary age, and unity and toleration among all. His views did not make any friends within his own Church of England.

The work of Edwards, Whitefield, and others who followed in their footsteps did much to usher in an era of defiance against the social and religious hierarchy in the colonies. An individual’s personal relationship with God took the forefront. This in turn led to the loosening of dependence between Great Britain and her subjects on religious matters. Because the Great Awakening was a national occurrence, much like the French and Indian War would be from 1754-1763, the colonies were able to find common ground and place aside differences between them for the collective good. For many young minds who would take the lead in the struggle for independence later, the Great Awakening was the first time that they were encouraged to defy norms instituted on them by the Crown and those in power. Religion and self-determination could co-exist. That belief was amplified as the eve of the American Revolution dawned, and the children of the Great Awakening then fought for the self-determination of the country.

In late 1775, following the outbreak of hostilities at Lexington and Concord, an army, divided into two wings, was formed to drive British forces out of Canada. One of those wings was led by Colonel Benedict Arnold. The expeditionary force organized at Cambridge, Massachusetts, in September, and from there marched to Newburyport. From that point the men would advance to the Kennebec River and begin an overland and riverine expedition to Quebec, where the force would rendezvous with another wing of the army commanded by General Richard Montgomery for an all-out assault on the fortress city.

The Old South Presbyterian Church in Newburyport housed the remains of Reverend George Whitefield. Within those walls, he had preached time and time again from the pulpit. Before departing the village, Chaplain Samuel Spring, accompanying the expedition, delivered a sermon to the soldiers and citizens who could fit inside the church. When all was said and done, Spring, Arnold, and his senior officers ventured into the basement with the church’s sexton to view Whitefield’s tomb. It and the coffin were opened, and the men cut pieces of the decaying reverend’s collar and wristbands, dividing them amongst the group as keepsakes before continuing their remarkable march to Quebec. The message of the Great Awakening was not lost upon the soldiers of the Revolution. Maybe carrying mementos of one of the movement’s greatest leaders would shroud these men in a spiritual cloak that would protect them in their new fight for liberation.