Fallen Timbers: Then & Now

The Civil War Trust recently had an opportunity to speak with Stacy Allen, Chief Park Ranger for Shiloh National Military Park about the Battle of Fallen Timbers and the state of the battlefield today.

Civil War Trust: Tell us about how Fallen Timbers fits into the larger Battle of Shiloh story

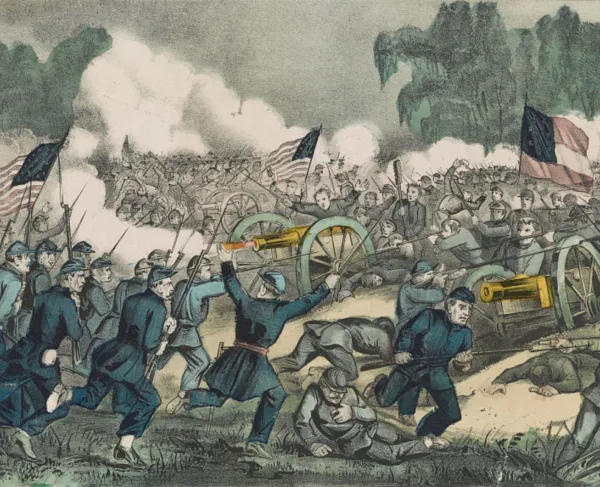

Stacy Allen: The explosive skirmish at Fallen Timbers, between the Union reconnaissance force commanded by William T. Sherman, with a mixed force of Confederate cavalry led by Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest, represents the final brief – but – furious close to the Battle of Shiloh. It is the final chapter in the battle story. After Fallen Timbers, its time to assess the damage and consequences of what has transpired. The fight marks a passage from one phase of the War in the Mississippi Valley, with the stage being set for the next. Amazingly, you can still sense this from the combatants, in their words and behavior in the days which proceeded from April 8, 1862. Everyone seemed ready to be finished with having to deal violently with the other for the time being. Shiloh was a punch in the solar plexus of all its participants. The men were literally exhausted, their energy drained, and the armies devastated by the Armageddon that was bloody Shiloh.

Sherman’s assignment, as expressed by his commander, Ulysses S. Grant, was to ascertain whether the Confederate Army, which had attacked them two days earlier, bringing on the titanic two-days of carnage in the Union camps at Shiloh, was in full retreat to its base at Corinth, Mississippi, or regrouping to make another strike at Grant’s base of operations on the Tennessee River at Pittsburg Landing. What Sherman determined from this reconnaissance on April 8th was the southern forces were full retreat – which was correct.

In spite of the furious clash with the Confederate horse-soldiers at Fallen Timbers, which inflicted further damage to the Federals, Sherman rightly reasoned the bulk of the Confederate infantry and artillery had passed Lick Creek the morning of April 8th, having traveled all night, retiring south towards Corinth, and that only cavalry was left behind to protect the retreat. Thus, this action – Fallen Timbers – and its landscape provide closure to the principle events constituting the Battle of Shiloh. It marks an end of one phase of the war and the start of another.

Could Grant and Sherman have done a better job of pursuing the retreating Confederate army? Did they let slip an opportunity to decimate their opponent?

SA: No! And I have always been fascinated with the criticism heaped upon military leaders of the past for failure to perform actions we ourselves have not been confronted by. There was never going to be a pursuit from the Shiloh battlefield and to imagine one was even possible is unrealistic. For one, the standing orders for Grant wait and Pittsburg Landing and not let the Confederates draw him into an engagement. Even though Grant initially, upon arrival at Pittsburg, seemed ready to move. But his superior, Henry W. Halleck, remained adamant Grant do nothing which would force the Confederates into a pitched general engagement prior to the arrival of Don Carlos Buell’s approaching army, and then new instructions for both commanders would be forth coming. When Grant advised it would be impossible to move with any celerity and Corinth could not be taken without meeting a large force – making Halleck’s undesired general engagement inevitable, or as Grant stated “from your instructions, is to be avoided.” With that, he advised Halleck he would hold his position and wait for further instructions.

Describe the composition of the Union and Confederate forces at Fallen Timbers

SA: The Confederate force is easier to account for. The largest organization present was John Wharton’s Texas Rangers (i.e. initially Terry’s Texas Rangers and later the 8th Texas Cavalry). The Rangers were commanded by Maj. Thomas Harrison, and he reported (Harrison wrote the only official Confederate report of the engagement) he had present 220 men. Harrison stated a company of Forrest’s cavalry was present, totaling 40 troopers. Initially, while Harrison conducted a reconnaissance of the Federal force he had been alerted was approaching, Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest, who commanded the 3rd Tennessee Cavalry, was not present. After conducting the scout of the Federal force and determining he lacked sufficient strength to attack, he retired to the field hospital, where he found a company of Wirt Adam’s Mississippi Cavalry, under the command of Capt. Isaac F. Harrison. Harrison cited the Mississippians totaled 40 troopers. At the hospital Harrison found Colonel Forrest. After discussing their options, it was determined to attack the enemy. Thus, being senior Confederate officer present, Forrest assumed command of the force of roughly 300+ horse-soldiers. Later accounts cite John H. Morgan was present with his Kentucky Cavalry squadron – but there is absolutely no primary documentation to support this assertion.

One interesting observation and assessment by Harrison was the nature of the ground and the advantageous position of the Union force when he conducted his own reconnaissance, rendered “a charge by cavalry extremely hazardous.”

The portion of the reconnaissance from Shiloh battlefield which would be engaged at Fallen Timbers on April 8th was under the command of Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman. The National force consisted of two brigades (their organizations significantly reduced over the past two days). These were his 3rd Brigade under the command of Col. Jesse Hildebrand, and his 4th Brigade, led by Col. Ralph Buckland (interestingly, when Sherman presented a paper on Shiloh in 1881, he fails to note Buckland’s brigade was present on the mission – this is probably on account it was not engaged in the actual skirmish). Sherman specifically cites only one regiment of cavalry present, which would have been two battalions of the 4th Illinois Cavalry under Col. T. Lyle Dickey (i.e. the father-in-law of the now mortally wounded Brig. Gen. William H. L. Wallace, who fell on April 6th at Shiloh infamous Hornet’s Nest position). However, Sherman states in the opening sentence of his report of the reconnaissance, “with the cavalry placed at my command.” Thus, he might have had more organizations at hand. Major Harrison refers to a force of Federal cavalry “about 300 strong” screening the advance of Sherman’s main body. The two battalions of the 4th Illinois assigned to Sherman’s Fifth Division reported 373 effectives engaged at Shiloh, and listed 6 casualties. So Harrison’s in the field estimate of their strength is indeed quite accurate.

Best estimate is Sherman’s total force, including Buckland’s brigade nearby in support, likely numbered 3,000 officers and men. While Wood’s column numbered roughly 2,100 rank and file.

William Tecumseh Sherman and Nathan Bedford Forrest, two towering figures of the Civil War, almost met an early end at Fallen Timbers. First tell us about how Forrest was wounded.

SA: Forrest was wounded in the final moments of the engagement. After flushing the Federal skirmishers and Dickey’s troopers, the Confederate troopers halted at the advance of Sherman’s primary force – the infantry of Hildebrand’s brigade. By all accounts Forrest advanced further, riding to within 50 yards of the approaching Federal brigade, now deployed in line of battle. Biographers write as if Forrest was still in pursuit of the fleeing Federals, but he may have simply proceeded further to ascertain and assess the situation to decided, “What next?”

Meanwhile, the southern troopers were retiring with the Federal prisoners they had taken among the Union skirmishers. It can be assumed the Federals most likely advanced a fresh skirmish line, which appears to have been well upon Forrest before the now isolated Confederate officer realized the impending peril. By all accounts, Forrest was fired on from several points – “from all sides” – according to his initial biographers Thomas Jordan and John P. Pryor (The Campaigns of Lieut.-Gen. N. B. Forrest, and Forrest’s Cavalry…New Orleans, 1868). They state a ball from an Austrian rifle (as cited by Jordan & Pryor), struck Forrest in the left side, just above the point of the hip-bone. The round penetrated to the spine and lodged there. It was a severe, possibly mortal wound, as the attending surgeon later concluded.

And how is it that Forrest escaped from his predicament at Fallen Timbers? Did this action add to his growing legend?

SA: According to Jordan & Pryor, once hit, Forrest’s right leg, benumbed by the shock, was left hanging useless in the stirrup. The wounded colonel turned his horse and fought his way clear, using his revolver to clear a path among screaming Union soldiers attempting to put him down. His horse was likewise wounded (mortally as it later proved).

For years, up until late 1997, I even interpreted the now legendary story of Forrest, who was now gravely wounded by the musket ball and virtually surrounded by the Federals, grabbed onto a luckless Union soldier and used the man as a shield to cover his back during his dash to escape, before discarding this individual as he departed the field. However, the earliest record of this now questionable feat by the seriously wounded Forrest is Robert Selph Henry’s “First with the Most” Forrest”, published in 1944. None of the sources cited by Henry, which were apparently used to base his narrative of Fallen Timbers actually cite this feat of using a Federal soldier as shield. All of them instead document Forrest fought himself clear using his revolver and make no mention of his grabbing up a Union soldier. I cannot say how or why Henry came up with this specific component of the Fallen Timbers historiography, which he forever added to existing public history record, but I now discount it as being true, given the eighty-two years it took to finally show up in a Forrest biography.

Fact is the only biography completed in Forrest’s lifetime was the Jordan & Pryor book, the manuscript of which Forrest reviewed, approved, and assumed responsibility for its accuracy. Thus, if Forrest had grabbed up a luckless Federal, I believe he most likely would have mentioned it. One salient fact about this first published biography is the authors did not have access to the later published Official Records, but did have access to Forrest’s personal papers. Thus, this biography places Morgan’s Kentuckians at Fallen Timbers, as well as citing Forrest commanded a squadron as opposed to a company of his own 3rd Tennessee. Forrest indeed had a squadron under his personal command from mid-day April 6th through April 7th, but Thomas Harrison’s report remains the only official record of the skirmish from the Confederate perspective, and Harrison cites only 40 of the Tennesseans were present under Forrest’s personal command at Timbers. It may have been the remaining portion of the squadron was nearby, performing some other mission when Forrest saw an opportunity to hit the Federal skirmishers. Harrison apparently lost track of Forrest during the charge, and cites in his report, written on April 11th in camp near Corinth, “I cannot state the loss of the companies co-operating with me. Colonel Forrest, I learn, was slightly [italics mine] wounded.”

Forrest apparently retired in a different direction from the Texas Rangers. Jordan & Pryor stating he galloped down the road and rejoined his own command. Sherman noted in 1881 he galloped off into the woods south of the road, where it is assumed he headed west. Jordan & Pryor write Forrest then gave orders to the next in rank to assume command, but avoid further action [italics mine] with so large a force. Forrest then sought medical aid at the hospital. Surgeons could not locate the ball and quickly ordered him to the rear. He rode to Mickey’s (i.e. properly spelled Michie’s, but documents in the O.R. use the other spelling) and into Brig. Gen. John C. Breckinridge’s main line (i.e. the primary Confederate rear guard) and according to Jordan & Pryor, Breckinridge ordered him to proceed to Corinth. He departed, accompanied by his adjutant, Capt. J. P. Strange. The wound became so painful Forrest quit the saddle and temporarily took transport in a buggy. However, that proved more discomforting, and he remounted to complete the ride, arriving in Corinth that night. There, a few hours later, his horse dropped dead from its wounds. It is apparent the Confederate surgeons believed his wound mortal, with the current lodgment of the ball near his spine far too serious an operation to undertake.

Forrest’s wound at Fallen Timbers sounds really severe. How long did it take Forrest to recuperate?

SA: Next day, Forrest was furloughed for sixty days and he journeyed home to Memphis. There, he recuperated and overcame a wound that usually kills. On April 29th, he learned from Lt. Col. John Kelly of discontent among the men of the regiment, prompted by deficient and defective food. Still suffering from his wound, he returned to Corinth and rejoined his men. Roughly one week after returning, while out reconnoitering the approaching Federal army group under Halleck moving south on Corinth, Forrest jumped his horse over a log, the act of which brought on such acute pain it became necessary to remove the lodged ball from his left side. The operation was severe, requiring him to again be absent from his command for two weeks.

Now tell us about Sherman’s experience at Fallen Timbers

SA: Sherman had a big day and in later years would remark it could have ended quite differently. In his after action report written on 8 April 1862, after he returned to his ravaged headquarters near Shiloh Meetinghouse, "About half a mile from the forks [this would be the forks of the Corinth and Ridge roads - with Sherman advancing west on the Ridge road] was a clear field, through which the road passed, and immediately beyond a space of some 200 yards of fallen timber, and beyond an extensive camp [this is the hospital they would seize after the skirmish].” Sherman stated he could see the enemy's cavalry in this camp, and after a reconnaissance he ordered the two advance companies of the Seventy-seventh Ohio, under Colonel Hildebrand, to deploy forward as skirmishers, and the regiment itself forward into line, with an interval of 100 yards. Sherman noted, “In this order I advanced cautiously until the skirmishers were engaged. Taking it for granted this disposition would clean the camp, I held Colonel Dickey's Fourth Illinois Cavalry ready for the charge."

Sherman describes the Confederates boldly charged into them, breaking through the line of skirmishers, when the entire 77th Ohio, retired in disorder. Sherman was disgusted with their behavior, citing, “The ground was admirably adapted to a defense of infantry against cavalry, it being miry and covered with fallen timber."

When the infantry broke, Dickey's cavalry also discharged their carbines, apparently too soon, for the shots had little effect, and according to Sherman, now unable to load the carbines, they too fell into disorder. Sherman dispatched orders to the rear for Hildebrand’s entire brigade to form line of battle, which was promptly executed. The broken infantry and cavalry rallied on this line. Sherman reported as the Confederate cavalry came before the main line, Dickey’s troopers, having reformed, charged and drove them from the field. This countercharge is not reported by Major Harrison in his report, in fact he states the Federals did not advance. It is clear the Confederates retired from the field, and Dickey’s troopers did reform and advance. We have to remember all these personal observations are being made from different perspectives and each is linked to time and space in orientation and description of events. Both accounts are probably right. Harrison left the area before the Federals again advance toward the hospital with Dickey’s cavalry in the lead. Thus, Sherman can describe they drove the southern cavalry from the field.

Years later, at the Annual Meeting of the Society of the Army of the Tennessee held at Cincinnati, Ohio, April 6-7, 1881, Sherman read a paper he had prepared on the Battle of Shiloh. In this account, he remembered as they approached the ridge, Forrest’s cavalry came down, with a yell, firing away with their pistols, riding over the skirmish line, over the supports, and right among him and his staff. For you see, Sherman was out with the skirmishers and remembered, “Fortunately, I had sent my adjutant, Hammond, back to the brigade to come forward into line quickly. My Aide-de-Camp, McCoy, was knocked down, horse and rider, into the mud, but I, and the rest of my staff ingloriously fled [italics mine], pell mell, through the mud, closely followed by Forrest and his men, with pistols already emptied. We sought safety behind the brigade in the act of forming 'forward into line,' and Forrest and his followers were in turn 'surprised' by a fire of the brigade which emptied many a saddle, and gave Forrest himself a painful wound, but he escaped to the woods on the south of the road."

Sherman adds in the 1881 paper read before his comrades, "I have seen Forrest since the war; have talked with him about this very matter, and he explained that he was left behind by Breckenridge [sic. Breckinridge] to protect this hospital camp, and if possible to check the pursuit by our forces which was naturally expected after the close of the battle of Shiloh. I am sure that had he not emptied his pistols as he passed the skirmish line, my career would have ended right there [italics mine]."

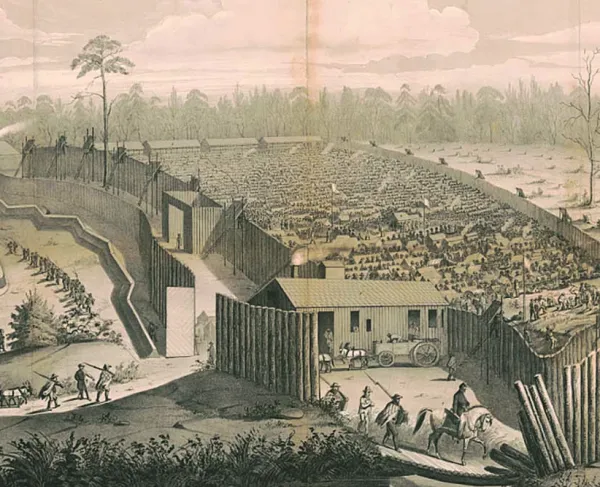

What can one see today at Fallen Timbers? How does the landscape compare to April 1862?

SA: An awesome historic pastoral landscape, native trees and cultivated fields much as it was in April 1862, minus the all important fallen timber. That timber by the way was most likely the result of harvesting bark from the trees for use in the tanning of leather at nearby tanneries located along Lick Creek. The trees girdled of their bark, soon die, grow weathered and eventually fall. The secondary name for the Ridge road, which is “Bark” road, informs us the area was being used to harvest bark for the tanneries. This deadening of a belt of timber would also assist in clearing the land for agricultural purposes.

Not only does the landscape possess the compelling story of Shiloh’s closure, but it also represents part of its beginning, in that elements of Breckinridge’s Corps bivouacked on this land, astride the road, on April 5th the evening prior the opening shots of the battle at Fraley field. Only a few modern residences are located nearby, and none are situated on the core of the combat zone available for purchase. An elderly seasonal ranger who once worked for me as an interpreter at the park grew up in the immediate area. He informed me he spent many a day as a child on the battlefield at Fallen Timbers and discovered numerous spent muskets balls and minie balls. It was he who informed me the ridge upon which Lyles’ hospital was located upon north of the road, terminates in a prominent point, from which you can see for miles to the northeast back toward Pittsburg Landing and the river valley beyond. If you’re Nathan Bedford Forrest on April 8th, needing to ascertain what threats to the hospital might be advancing off Shiloh battlefield, then you are on that point looking intently eastward.

How will preserving Fallen Timbers help in the telling of the Battle of Shiloh story?

SA: Preserving this land provides closure to the carnage of Shiloh – for the final shots of this first truly titanic battle of the Civil War are fired on 8 April 1862, not 7 April 1862. The question of whether the momentous battle continues or not is answered by Sherman’s brief but furious confrontation with Forrest at Fallen Timbers and capture of the “last of the Rebel hospitals” as he would recall it. A page of history is turned at Timbers, and a new chapter of the war in the West and campaign for the Mississippi Valley begins. Within days, a force dispatched by Halleck and led by Sherman, disembarks from transports and destroys the trestle bridges of the Memphis & Charleston R.R. at Bear Creek near Eastport, Mississippi (April 12-13). The railroad line is again successfully severed, for it has already been pounced upon by a 10,000-man force under Brig. Gen. Ormsby M. Mitchell, a sizable component of Buell’s command, which entered Huntsville, Alabama, on April 11th. As a result, direct Confederate rail connection and communication eastward from the Mississippi to Richmond is severed. That same evening, Halleck’s arrives at Pittsburg Landing and preparations start under his personal direction for what will be the advance of his army group upon Corinth – which formally starts on 29 April. And once again, Sherman’s division will advance through the area of Fallen Timbers in making its initial movement.

As stewards of Shiloh’s history, we are excited about the effort to preserve the final action of the battle of Shiloh on the ground where it was fought; and look forward to making the site accessible for future generations to visit, understand, and appreciate.

Related Battles

13,047

10,669