During the Civil War, music, musicians, and the role of music was just as diverse as it is today. In the world of classical music, Western art music experienced what later became known as the Romantic Era. Lasting from approximately 1830-1900, this musical style was defined by the exploration and expansion of expression and the inventiveness of techniques and instruments to achieve it. Symphonies became bigger and longer, piano playing reached a new level of virtuosity, music drew from art and literature, and operas were even more dramatic. Composers of this era included: Tchaikovsky, Brahms, Mahler, Verdi, Wagner, as well as many others. People living in large metropolitan areas with resident symphonic orchestras, or visiting orchestras, were exposed to these composers and their music, as well as the works of earlier prominent composers such as Mozart, Beethoven, and Bach.

For a larger portion of our country, an opportunity to hear this type of music was limited. That does not mean that what they listened to was any less diverse. The diversification of these genres spread and took hold regionally. One such genre, shape note, began in New England but spread and took hold in the South. It was a style of music based on four notes. In other regions of the country, different genres of music were popular. In Louisiana, for example, African slaves brought with them a tradition of drumming and drum circles. As religious fervor swept through the country in the 1830s and 1840s, spirituals and hymns became a common form of music heard all across the United States. Slaves added their unique drumming and rhythms to these traditional hymns and created their own spiritual music. In the 1820s, in New England, genteel English ballads were popularly heard. By the 1840s-1850s, white composers were writing music based on the African American traditions of music and performing traveling shows known as minstrels. Another popular genre that grew before the Civil War were brass bands or community bands. Once the armies were formed and in the field, the music of military fife and drum corps became popular again, both within the armies and the homefronts supporting them.

With all of these different musical genres, and many more in the years leading up to and during the Civil War, what role did they play in the everyday lives of civilians and those in the armies? People back then listened to and used music in much the same way as we do today. They attended concerts or minstrels shows as a source of entertainment. They sang hymns and spirituals at church services and religious events. The military, however, used music differently during this time period. Military bands and the music they played inspired patriotism and fighting spirit. It was played on the march before and after battle. Military bands also played music that had very special and important roles, instructing soldiers when to eat, go to bed, and even charge into battle. Although brass bands and their style of music existed before the Civil War and had been imported from Europe into the new world over a century before, American military brass bands and music rose to a higher prominence than even during the American Revolution as a direct result of the Civil War itself. Indeed, both the Union and Confederate armies in all theaters of the war utilized these musical groups. And even though American military bands still exist and are used to inspire patriotism, they are no longer used on the battlefield. Their story, then, began with the beginning of the war and the need for both governments to raise massive armies.

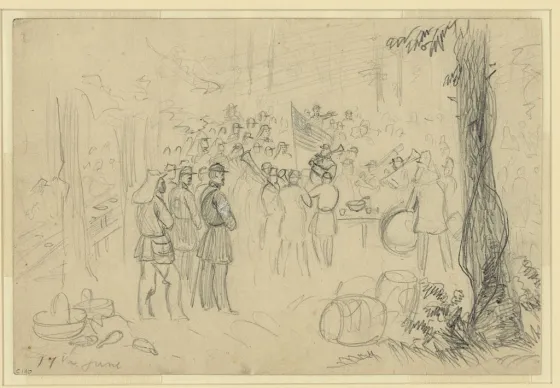

As war fever swept across the North and South, and volunteers answered the calls of Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis, military units organized and entered military service. Military bands also followed this path into military service. Like their counterparts in the infantry, artillery, and cavalry, military bands were typically raised when state and local units were formed and were proactively utilized to help gain the attention of potential enlistees to boost overall recruiting numbers in both the North and South. Oftentimes, a small town’s community band members would join to provide support for their newly enlisted infantry and cavalrymen. Their main objective was to provide support to enlisted men which consisted of performing music for drills and most importantly keeping morale up during these unprecedented times.

While new recruits and volunteers learned the art of war in these early weeks and months of their service in the spring and summer of 1861, the appreciation of military bands and their performances grew. It only deepened as the war continued. Musicians often were credited with providing a sense of escape from the horrors and stress of war. When musicians or bands played for the troops while in camp, it also allowed for bonding among the troops. In a postwar report on the role of the U.S. Sanitary Commission during the war years, Frederick Law Olmsted concurred on the importance of military bands. He noted, in particular, the feelings that soldiers had about having military bands in their units and in camp:

"These bands are not generally of the first order, by any means, but are sufficiently good to please and interest the great majority of the soldiers. The men are almost universally proud of their band, particularly so if it be of more than average respectability...it raises the spirits of the men, warms their patriotism and their professional feelings as soldiers and thus actually tends... to promote health, discipline, and efficiency."

Further exploring the purpose and importance of military bands, in particular to the soldiers in the Union army, Olmsted cited the experience of Doctor J.H. Douglass, a military inspector, while in Poolesville, Maryland after the battle of Ball’s Bluff in October 1861. “I am convinced that music in a camp after a battle...is of great importance,” wrote Douglass. In talking with one of the soldiers in the camp, Douglass recalled that one, in particular, spoke on this very topic, stating, “I can fight with ten times more spirit, hearing the band play some of our national airs, than I can without the music.” The importance of military music and bandsmen in the early period of war and their purpose, then, is undeniable. But what comprised these bands, and how were they organized?

As volunteers continued to organize and muster into service, musicians who were enlisted as band members could be placed in either military bands or as military field musicians. Bands were more commonly used in parades, military reviews, funerals, during inspections, when commanding officers addressed their men, and while in camp to provide comfort and camaraderie. These larger groups included more wind instruments than their counterparts. Field musicians, on the other hand, included men and boys, often as young as twelve years old, who played fifes, drums, and bugles. Commanders utilized these musicians to play military commands, help with troop movements on small and large scales, and finally to provide command and control during the heat of battle. Because of the responsibility that the fife and drum corps had, their musical training was far harder than those in brass bands. The size of these two different types of military ensembles was based upon the U.S. Army regulations that were established before the American Civil War. These regulations were also used by Confederate armies to establish their military ensembles. In total, regiments in both armies were authorized to permit up to sixteen men to enlist and serve as military musicians. This number was also based on the number of men who were available and able to fill the ranks and changed as the war progressed.

With the war underway, and both sides looking for advantages on the battlefield, technological advancements in all aspects of warfare commenced. This also included technological advancements to instruments of the era. Expanding technology in the decade leading up to the war and during the war itself led to instruments like the bugle to receive keys. With this advancement, the bugle became the leading voice in the genre and replaced the clarinet in American melodic music as did other brass instruments. By the 1850s, technology again revolutionized brass instruments with valves. The two valved brass instruments that played a big role in military bands during the Civil War were the cornet and the Saxhorn. Over-the-shoulder Saxhorns now became a common instrument within American brass bands. Developed by Adolph Sax during the mid-to-late 1830s, Saxhorns featured bells that faced to the rear of the player. This style of instrument proved to be beneficial since the band often marched ahead of the troops. The rear-facing bells allowed the sound to travel from the instrument to the troops behind them. Additional instruments in military brass bands included snare and bass drums, fifes, and even clarinets. Being proficient on these instruments, and performing music that lifted soldiers’ spirits or directed them on how to maneuver on a battlefield was not the only duties military bandsmen of the Civil War era performed.

Military musicians initially enlisted as noncombatants, but often and willingly assumed the roles of stretcher bearers and medical assistants during skirmishes and larger battles. Bandsmen were often responsible for removing wounded soldiers from the fields of combat. On other occasions, depending on circumstances on the field, they were tasked with the gruesome detail of burying the dead. Additionally, they helped surgeons behind the battle lines with amputations and additional medical procedures. Julias A. Leinbach, a member of the 26th North Carolina Band wrote of these other duties in his diary:

"It was therefore with heavy hearts that we went about our duties caring for the wounded. We worked until 11 o’clock that night...At 3 o’clock [the next morning] I was up again and at work. The second day our regiment was not engaged, but we were busily occupied all day in our sad tasks [of caring for the wounded]. While thus engaged, in the afternoon, we were sent...to play for the men [who were not injured], thus perhaps, [to] cheer them somewhat….We accordingly went to the regiment and found the men much more cheerful than we were ourselves. We played for some time, the 11th N.C. Band playing with us and the men cheered us lustily. We got back to camp after dark and found many men in need of [medical] attention. Some of those whom we had tried to care for during the day had died during our absence….We continued our administrations until late at night and early the next morning."

In the larger context of the war and the historical scholarship that has been published since its conclusion, military bandsmen and the roles they assumed are often overlooked. Field musicians provided essential duties of regimenting daily army life, both in camp and on the battlefield. Larger military bands provided soldiers with the opportunity to escape the horrors of war through music and at times, lift sagging morale. As the war dragged on, however, the expense of military bands, both private and governmental, became an item both governments could no longer afford. Yet, as the number of bandsmen and field musicians decreased as the war moved into what became its final years, the memory and role of military musicians grew. Today, their legacy remains in the martial music composed and performed from 1861-1865, their material culture left behind for future generations, and the descendent American military ensembles and musicians of the twenty-first century.

Further Reading

-

Music of the Civil War Era By: Steven H. Cornelius

-

Battle Hymns: The Power and Popularity of Music in the Civil War By: Christian McWhirter

-

Songs of the Civil War By: Irwin Silber