The Civil War in Hampton Roads: Fort Monroe

Arriving in Virginia, English settlers immediately recognized the strategic significance of a spot near the mouth of Chesapeake Bay shielded from Atlantic storms and located on a deepwater channel. They named it Point Comfort and established the first military presence there within two years of landing at Jamestown.

In August 1619, the site witnessed a tragic chapter in American history — the arrival of the first Africans transported to Virginia unwillingly. They had been seized of a Portuguese slave ship by a privateer bearing a Dutch letter of marque and, although they were considered indentured servants at the time, the incident is recognized as the beginning of slavery in the British North American colonies.

Military installations at Old Point Comfort were built, repaired and expanded at various times throughout the colonial period, including an artillery battery established by the French West Indian Fleet during the 1781 Siege of Yorktown. British naval incursions up the Chesapeake Bay during the War of 1812 prompted the United States to plan a new system of coastal defenses all along the Eastern Seaboard.

To watch over the important waters of Hampton Roads, President James Monroe commissioned the largest stone fort ever built in the United States. Construction began in 1819 and, upon its substantive completion in 1834, Fort Monroe — with its 32-pound guns that could fire more than a mile to protect critical shipping channels — was deemed the Gibraltar of the Chesapeake. It functioned as an assembly, training and embarkation point for American forces during the Seminole Wars, suppression of Nat Turner’s Rebellion, Black Hawk War and Mexican War. A series of artillery schools established at Fort Monroe educated many of America’s finest gunners.

In the spring of 1861, following Virginia’s secession from the Union, President Abraham Lincoln quickly moved to reinforce Fort Monroe, lest it face a similar fate as Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. This action meant the bastion remained in Union hands throughout the war; for a time, the last Federal foothold in Tidewater Virginia, the navy having burned and abandoned the Norfolk Navy Yard to the Confederates.

Fort Monroe played an important part in numerous Union initiatives: a crucial link in the Anaconda Plan’s naval blockade, the launch point for the 1862 Peninsula Campaign, logistical support for gunboat operations based out of City Point during the late-war Petersburg Campaign. Despite these military contributions, Fort Monroe only once fired at an enemy, ineffectual rounds that bounced off the ironclad CSS Virginia during the March 1862 Battle of Hampton Roads. It was a logistical hub, too — a major hospital and official point of transfer for mail sent between locations in Union and Confederate territory.

Perhaps Fort Monroe’s greatest contribution to American history, however, came in an unlikely context; a seemingly bureaucratic decision that ultimately helped shape the tenor and tone of the Civil War.

At the outset of the war, a number of enslaved workers had been leased to the Confederate army to construct defensive batteries. On the night of May 23, 1861, Frank Baker, James Townsend and Shepard Mallory escaped, stole a small boat and rowed to Fort Monroe to seek asylum. The Confederates, per the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, demanded their return. The legally trained Union commander, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler, refused; as he explained in a May 27 letter, since Virginia had seceded from the United States, that statute could not be applied. Further, since the men had been employed in an act of war against the United States, he could seize them as enemy property, or contraband of war.

The decision was problematic, in that it tacitly recognized the sovereignty of the Confederacy by acknowledging that a U.S. law was not applicable. Moreover, no fundamental change in status was immediately achieved for the three men; they were not declared free and were put to work by the army without pay. However, the so-called Fort Monroe Doctrine set in motion an evolution in thinking that would continue through the First and Second Confiscation Acts, the Emancipation Proclamation and the establishment of the United States Colored Troops.

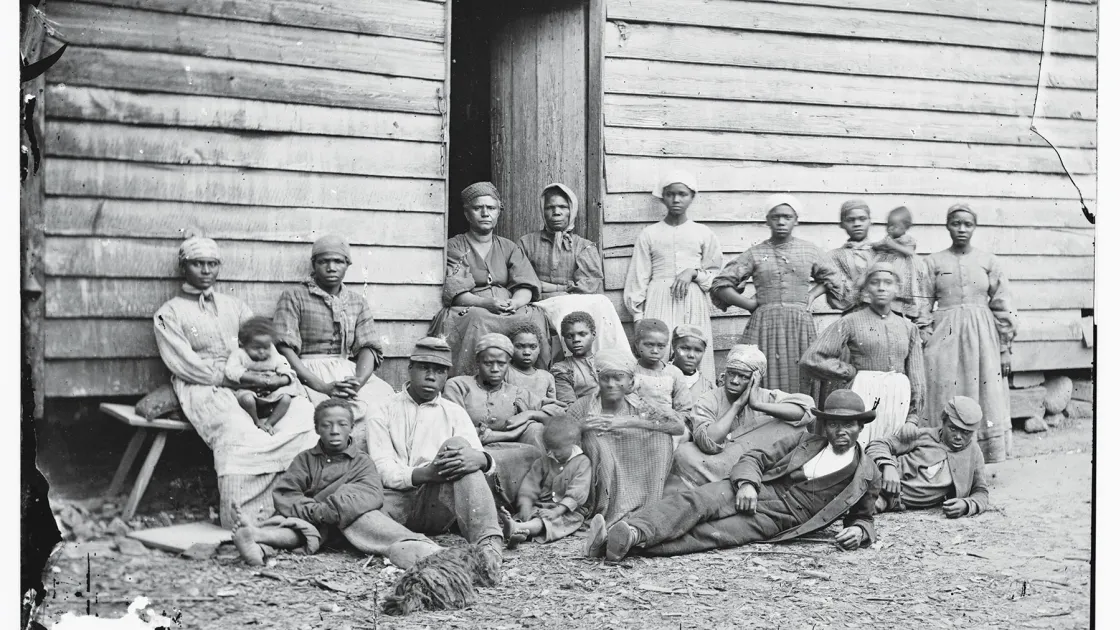

Rapidly becoming known as Freedom’s Fortress, Fort Monroe was a powerful symbol for enslaved people, offering them a legitimate way to seek their own liberation. By autumn, the Grand Contraband Camp had been established nearby. The facility that would ultimately be home to more than 10,000 formerly enslaved persons quickly became a locus for education of African Americans, which had been forbidden in Virginia, ultimately leading to the founding of Hampton University.

Fort Monroe remained an active military post until 2011, when it was decommissioned as part of the 2005 Base Realignment and Closure process and its functions transferred to nearby Fort Eustis. On November 1, 2011, President Barack Obama used his authority under the 1906 Antiquities Act to declare Fort Monroe a national monument and the 396th unit of the National Park System. In August 2015, on the anniversary of the first Africans’ arrival in Virginia, the Commonwealth donated 121 acres to the park, including many of the fort’s most important historic buildings.