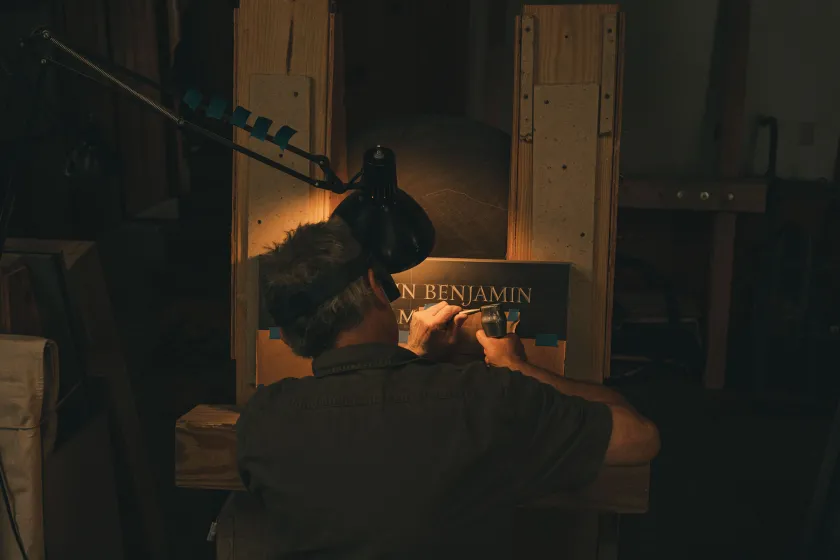

Paul Russo v-cutting one of the French officers' grave markers at the John Stevens Shop, Newport, R.I.

For 316 years, the John Stevens Shop has been hand chiseling monuments and grave markers for great leaders, war heroes and everyday people. Recently, they were commissioned to create markers for two French officers who crossed the Atlantic to help save the colonists in 1780. The Trust was lucky enough to observe them at work.

The young man who boarded a ship to emigrate from Oxfordshire to England’s North American colonies in 1698 had no inkling that his name would linger on three centuries later as a standard of outstanding craftsmanship. But the John Stevens Shop still stands on Thames Street in Newport, R.I., where its resident artisans have been producing exceptional stone carvings since 1705.

The Stevens clan etched its way into history over the course of 220 years, before selling the shop to native Newport artist John Howard Benson in 1927 and beginning a new family legacy of tradition and excellence. The eldest Benson was an internationally renowned calligrapher and educator who authored the instructional book The Elements of Lettering and designed the Iwo Jima/ Marine Memorial inscriptions. Upon his death, the shop passed to a second generation.

John Everett Benson (“Fud”) — who still tinkers in carving, sculpture and other artistic media in a studio behind the shop — continued the tradition of carving onto monumental edifices, designing and working directly in the stone of iconic institutions, including the John F. Kennedy Memorial, the National Gallery of Art, the Vietnam Memorial and the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial.

Like his father before him, Nicholas Benson began apprenticing in the John Stevens Shop at age 15. He was still a teenager when he was handed a chisel and carved into the west front of the National Gallery of Art West Building, a moment that helped shape his life. After studying drawing and design as an undergraduate in the United States, he undertook a specialized course in calligraphy, type design, typography and drawing at the Basel School of Design in Switzerland. In 1993, five years after completing studies and returning home, Nick Benson took the reins of the business in his steady and precise hands.

Although careful to describe carving as a craft rather than an art, Benson could easily be mistaken for a virtuoso given the passion he summons to describe his vision and his process. On monumental projects like the Martin Luther King, Jr., Memorial, World War II Memorial and Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial, he created custom typefaces meant to evoke specific elements of the overall design. But his work is about much more than aesthetics; legibility and durability must always remain front of mind, as must the physical reality of working in stone.

Despite the passage of centuries, work in the John Stevens Shop is still performed in a rhythm that would be familiar to the many craftspeople who came before. Designs are still created by hand and applied to the stone with fine-tip paintbrushes before they are chiseled into relief. While the cutting implements may now be made of tungsten rather than colonially available metals, the mallets that steadily strike them are typically fashioned by hand, weighted and gripped perfectly for the user. Shelves are lined with the tools favored by the generations before, occasionally brought back into circulation.

The shop itself is a kind of time capsule. The original headstone for John Stevens — replaced with a loving copy when it became too damaged to stand — shares space alongside a prototype carving of Yale University’s installation honoring its Medal of Honor recipient alumni. A larger-than-life, art deco portrait of John Howard Benson towers over the studio. Near the front window and still in use, albeit lightly, is a drafting desk dating to the shop’s early decades, and hanging on the wall, a framed advertisement for the shop’s services in a Newport newspaper, dated 1781.

Thus, Benson took it as a sign when he was approached by the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route National Historic Trail to create headstones for two of the earliest French casualties of the Revolutionary War, who had rested in Newport without proper markers since their demises in 1780. That their work would physically and symbolically be joining that of their predecessors in the oldest sections of Trinity Church’s yard was a moving realization. In one way, however, Paul Russo, who specializes in headstones, treated the commission like any other — he immersed himself in learning as much as possible about Major Pierre du Rousseau, Chevalier de Fayolle, and Lieutenant Augustin Benjamin Lavilmarais as a way of honoring their lives as he set down their names for eternity

Watch the exclusive Trust video about Nick Benson and the John Stevens Shop below.