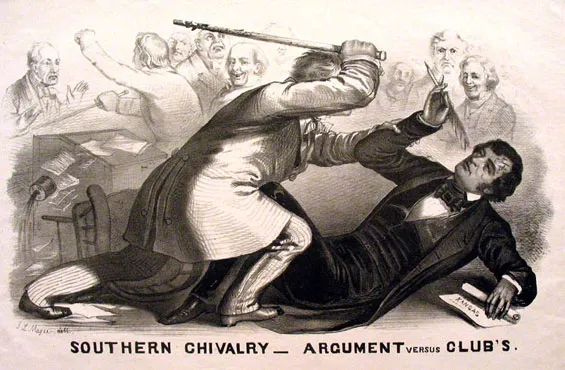

Newspaper headlines shocked readers in late May 1856 with descriptions of a violent attack within the United States Capitol Building. Preston S. Brooks had nearly bludgeoned Charles Sumner to death. “Cowardly assault upon Senator Sumner,” declared the Hartford (Connecticut) Courant. The Edgefield (South Carolina) Advertiser simply referred to the incident as “Mr. Brooks’ chastisement of Senator Sumner,” while an Alabama newspaper opined, “Sumner has been needing something of the sort since the first day he put his foot into the Senate chamber.” The wide variety of reactions illustrated the growing sectional differences and foreshadowed the rising violence that culminated five years later with the outbreak of the American Civil War.

Early in his career, Massachusetts native Charles Sumner had sworn against a life in politics. That changed in 1848, when the Whig Party, with whom he identified, nominated Zachary Taylor for president. Taylor was a slaveholding southerner, and Sumner believed the Whigs had thus betrayed their strong base of support from northern abolitionists. He advocated for a schism and the establishment of a new party. The Free Soilers gathered momentum from disillusioned northerners, and the party rewarded Sumner with an endorsement for United States Senate. Once in Congress, Sumner campaigned to rectify his issues with the Compromise of 1850 and Fugitive Slave Act. He also opposed the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, which amended prior compromises to allow territories to decide issues for themselves when they applied for statehood. The legislation seemed democratic, but Sumner predicted that outside agents would influence Kansas’s future, particularly with the growing issue of slavery. Indeed, the region became a battleground in 1856 as forces opposing and supporting slavery clashed for control. Sumner blamed this violence on Congress and gathered his thoughts into a passionate address, “The Crime Against Kansas,” that took two days to deliver.

During his speech on May 19-20, 1856, Sumner described southern interference in the region as, “the rape of a virgin Territory, compelling it to the hateful embrace of Slavery; and it may be clearly traced to a depraved desire for a new Slave State, hideous offspring of such a crime, in the hope of adding to the power of Slavery in the National Government.” Sumner stated that the violence in Kansas was plotted by the south and spoke forcefully against the bill’s authors, Stephen Douglas and Andrew P. Butler. He declared that Butler, “has read many books of chivalry, and believes himself a chivalrous knight, with sentiments of honor and courage. Of course, he has chosen a mistress… who, though ugly to others is always lovely to him, though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight; I mean the harlot Slavery.”

His accusation against a fellow senator and condemnation of the entire state of South Carolina, Butler’s home, shocked even those who agreed with Sumner’s assessment of the situation in Kansas. Southerners meanwhile deemed the Massachusetts abolitionist’s rhetoric as incendiary. Some personally viewed it as an affront to their honor, and retaliation for Sumner’s outspokenness came swift. Preston S. Brooks served as a representative from South Carolina and was a distant relative to Butler, who had been absent during Sumner’s speech. Brooks believed Sumner had directly insulted Brooks’s prided institution of slavery, his family, his native state, and himself. He followed the strict code of honor common among the plantation elite in the south and had been involved in several duels in the past, but believed that because Sumner had proven himself to not be his equal in status, the Massachusetts senator deserved a more humiliating punishment. Brooks stalked Sumner for the next two days, hoping to accost him on the Capitol grounds, but the Massachusetts senator unknowingly evaded these challenges.

Determined to correct the offense to his honor, Brooks decided to settle the score inside the Capitol. On May 22 he lingered after an adjourned session while the Senate chamber emptied. Brooks waited a full hour for a few ladies who were present to depart. Sumner had meanwhile busied himself writing letters and pulled his chair in close to his desk, which was bolted to the floor. Brooks then approached him and stated: “Mr. Sumner, I have read your speech with great care, and with as much impartiality as I am capable of, and I feel it my duty to say to you that you have published a libel on my State, and uttered a slander upon a relative, who is aged and absent, and I am come to punish you.”

Brooks walked with a limp, the effect of a dueling wound he received in 1840, and always carried a cane. He proceeded to slam this wooden rod down on Sumner’s head and continued to viciously beat the senator. The seated Sumner could not ward off Brooks’s blows and was rendered defenseless by the sudden attack. He sought to escape but could not pry himself out of the desk. Two other southern delegates, Lawrence Keitt and Henry Edmundson, accompanied Brooks and prevented anyone from intervening. The attack lasted only one minute, but Brooks claimed to give Sumner “about 30 first rate stripes with a gutta perch cane… Every lick went where I intended it. For about the first five or six licks he offered to make fight but I plied him so rapidly that he did not touch me. Towards the last he bellowed like a calf.” Sumner eventually freed himself from the desk, though Brooks continued to inflict heavy blows upon him. Several congressmen finally restrained Brooks and assisted the battered Sumner to safety.

Brooks justified his actions in a letter the next day to his brother. “Sumner made a violent speech in which he insulted South Carolina and Judge Butler grossly. The Judge was and is absent, and his friends all concurred in the opinion that the Judge would be compelled to flog him. This Butler is unable to do as Sumner is a very powerful man and weighs 30 pounds more than myself. Under the circumstance, I felt it to be my duty to relieve Butler and avenge the insult to my State.” A House committee investigated the incident and proposed expelling Brooks. “This they can’t do,” he predicted to his brother. “It requires two thirds to do it and they can’t get a half. Every southern man sustains me.”

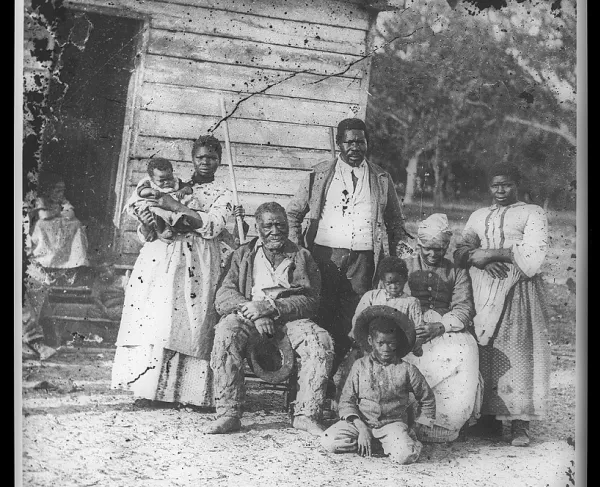

Brooks was correct in assuming the attitude in the south and the inability of Congress to formally remove him. Most southern newspapers praised Brooks’s action and compared Sumner’s beating to that which a disobedient slave would receive. “You have put the Senator from Massachusetts where he should be,” rejoiced a group of South Carolinians in a public statement. “You have applied a blow to his back. He has undergone the infamy of personal punishment. His submission to your blows has now qualified him for the closest companionship with a degraded class.” Abolitionists used a similar rhetoric, but insinuated that southerners had been become so wrapped up in their institution that they now deemed it proper treat anyone they regarded as inferior, even a member of Congress, with authoritarian discipline as toward a slave.

The House vote to expel Brooks failed, but he voluntarily resigned to prove his support back home. His district unanimously reelected Brooks to return to his position, though he would only serve a short time before dying from the sudden onset of illness in January 1858. Sumner’s traumatic injuries meanwhile prevented him from attending any sessions for the next three years, but he was nevertheless reelected despite his absence. Rather than hold a special election to fill Sumner’s seat, Massachusetts politicians decided his vacant chair would provide a powerful symbol in the Senate as a reminder of the atrocities inflicted by the slaveholding south.

Southern newspapers hoped that the violence would cower abolitionists into silence, one declaring, “We trust other gentlemen will follow the example of Mr. Brooks… If need be, let us have a caning or cowhiding every day.” Despite their posturing, the assault on Sumner galvanized northern supporters into an even stronger coalition. One historian theorized that the caning played a key role in the ascension of the Republican Party, an evolution of Sumner’s Free Soilers. Among numerous examples he cited was a new member of the party who joined after the incident. “Had the Slave power been less insolently aggressive, I would have been content to see it extend,” the former Democrat wrote, “but when it seeks to extend it sway by fire & sword… I am ready to say hold enough!”

Sumner also identified with the Republicans and frequently pushed its leaders to adopt a radical treatment toward the south. The new political movement—once treated with such contempt by southern elites as to desire whipping it into submission as they would a slave—quickly gathered support. Within four years they elected Abraham Lincoln as president and ultimately defeated the southern Confederacy as violence extended past the Congressional halls and into the states.