The Battle of Pell's Point

In October of 1776, General George Washington was reassessing where his bloodied army could make a stand. In August, his men were defeated in the Battle of Long Island, suffering major losses. A large portion of his army was almost destroyed at Brooklyn before they were successfully ferried across the East River onto Manhattan Island. In September his men were routed at the Battle of Kip’s Bay, and he was able to stave off disaster at the Battle of Harlem Heights. The British took possession of New York City and looked to attack Washington again.

General William Howe decided rather than a frontal attack on Washington’s strong position at Harlem, he would flank Washington’s force by landing his army at Throg’s Neck and push his army up and take Kings Bridge (in Washington’s rear) which would have effectively bottled up Washington’s men on Manhattan Island. On October 12, 1776, 4,000 British soldiers landed at Throg’s Neck on the East River. However, they soon discovered that the small peninsula was more like an island. Thirty Americans under the command of Colonel Edward Hand stopped the British from crossing the narrow causeway while American reinforcements arrived to stop the British from advancing inland. Frustrated by this failure, Howe planned to move his men up to Pell’s Point, three miles north.

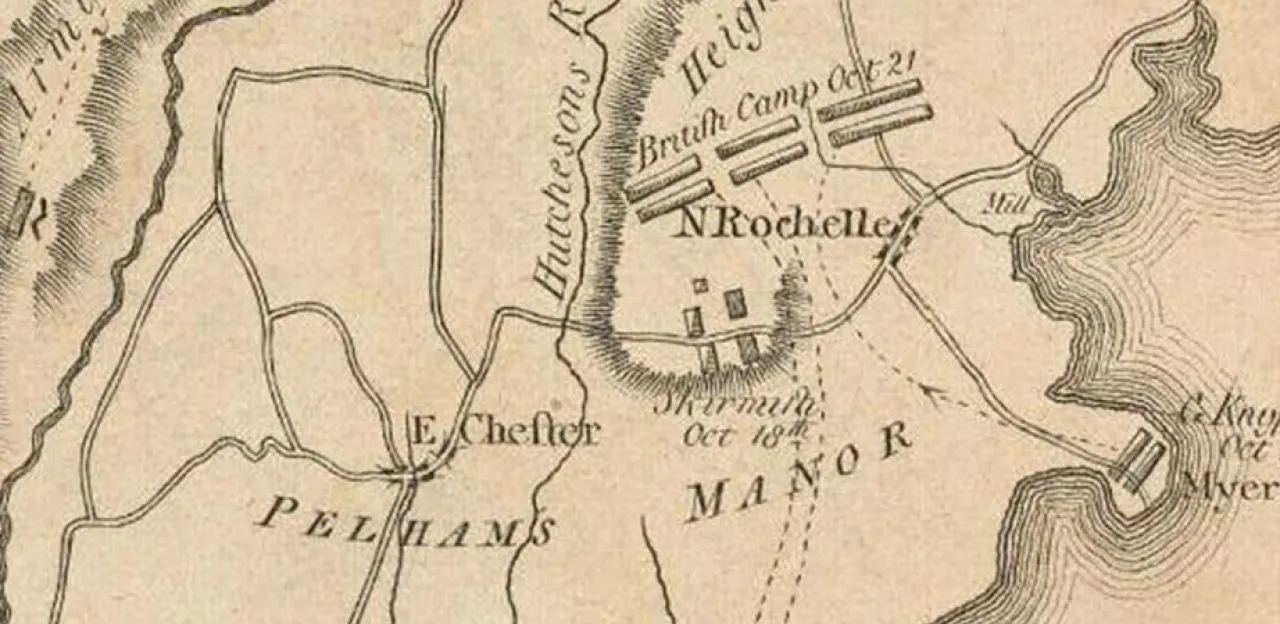

Washington, realizing his precarious position, decided to move his army off Manhattan Island and head towards White Plains, New York on the mainland. On October 18, 1776, Howe’s 4,000 men landed at Pell’s Point and began advancing on the road inland. Stationed in the area was Colonel John Glover and his brigade consisting of four Massachusetts Continental regiments, including his regiment of Marblehead fishermen who had helped evacuate Washington’s army across the East River in August. His brigade numbered about 750 men. Glover dispatched 40 men to engage the British vanguard as he prepared an ambush on the road towards New Rochelle. Using stone walls to his advantage, Glover staggered his regiments behind numerous walls along the road.

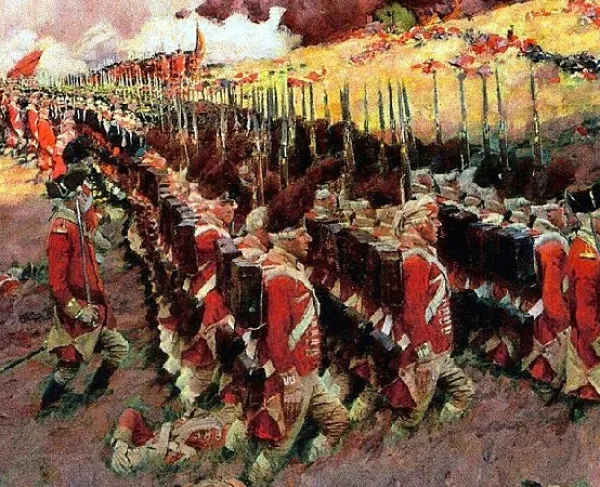

The American vanguard engaged the head of the British column and the two sides fired into each other. Both sides took casualties. As British reinforcements came up, Glover ordered his vanguard to fall back along the road. This was done in good order, and the British followed the retreating men. Waiting up the road behind a stone wall were some of Glover’s men of the 13th Continental Regiment. They waited patiently until the British were just thirty yards from their position, then rose up and fired a deadly volley of musketry into the stunned British and Hessian troops. The advance British soldiers fell back towards their main body. The British took nearly an hour to reorganize and then all 4,000 men with seven cannon advanced back up the road.

The British renewed the attack on Glover’s men, and after firing into each other for a while, Glover’s men fell back in good order again. The British and Hessian soldiers followed the retreating Americans. As they advanced further up the road, another of Glover’s regiments, the 3rd Continental Regiment, was waiting behind another stone wall. When the British advanced within a few yards, they too rose up and fired into the advancing column. The firing was incredibly fierce at this second position and halted the British for almost an hour as both sides poured deadly fire into each other. Glover noted that his men fired at least seventeen rounds into the advancing enemy. At one point in the fighting here the commander of the 3rd Continental Regiment, Colonel William Shepard was shot through the neck with a musket ball, but he eventually recovered. Glover ordered his men back along the road to a third position where more Massachusetts men from the 26th Continental Regiment laid in wait behind a stone wall. The British advanced to this third position and again were hit with musket fire from the Americans along with some artillery.

Fearing his position may be flanked, Glover did not stay in this position long and ordered his brigade to fall back across the Hutchinson River to rejoin Washington’s main army. Their retreat was covered by the Marbleheaders of the 14th Continental Regiment. An artillery duel between the two armies across the river ended the day’s fighting.

Glover had lost 8 men killed and 13 wounded. Howe reported 3 killed and 20 wounded, though this figure likely did not include the many Hessians who likely took more casualties. Estimates of British and Hessian casualties vary greatly, but it is likely that more than a hundred Hessians were killed or wounded. Many of the British wounded were treated at the nearby St. Paul’s Church in Eastchester.

Regardless of the casualty numbers, the battle helped to slow the British advance and allowed Washington time to evacuate to White Plains. The stubborn tenacity of Glover’s men and their use of stone walls for protection also made Howe more cautious as his army advanced inland, fearing they could be constantly ambushed. Washington was impressed with Glover’s brigade and thanked them and told the rest of the army that he hoped they would fight in the coming days “with equal duty and zeal whenever called upon.” The Americans had landed a blow on the British Army, but Washington continued to fall back towards White Plains where the two armies would meet again on October 28, 1776.

Related Battles

155

458