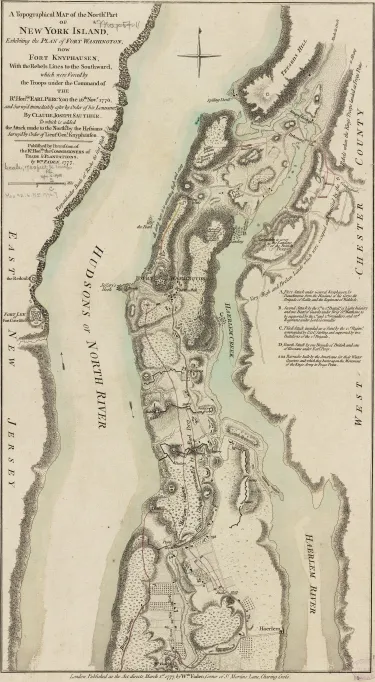

Perched on the highest point on Manhattan Island near the most northern tip, the location of Fort Washington was picked by the senior military brass of the Continental Army in the summer of 1776. This included General George Washington who surveyed the spot in late June 1776. Along with a fort, named after the second-in-command of the Continental Army, Major General Charles Lee, in New Jersey, Fort Washington would help defend the Hudson River corridor from being menaced by the British Navy.

The design of the fort took on a pentagon shape with five bastions made entirely of earth and when finished would encompass about four to five acres within the walls. Due to the rocky composition of the soil, no trenches or ditches were dug around the exterior of the fort. South of the fort, however, on the hilly terrain, was a three-lined defensive network comprised of trenches and foxholes, each within supporting distance, although the last line was not completed by November 1776. Even the Hudson River saw defensive measures, as hulks of ships, loaded down with boulders and other impediments, were implemented to stop naval vessels from skirting by the twin forts.

With the disastrous string of engagements that the Continental Army lost around New York during the summer and early fall of 1776, Fort Washington, though hastily constructed, stood resilient. In early November, German mercenaries (auxiliaries), collectively called “Hessians”, were repulsed in an attempt to take the fortification. However, this minor victory would have severe repercussions for the Americans. As General William Howe chased George Washington’s main forces, a British detachment was sent to Harlem Heights under the command of General Hugh Percy to watch the American garrison at Fort Washington.

The small victory in early November convinced Colonel Robert Magaw, Fort Washington’s commander, and General Nathanael Greene that the installation could be successfully held and was potentially impregnable. Magaw, a pre-war Pennsylvania lawyer, had served in the militia for his home colony and was elected colonel of the 5th Pennsylvania Battalion. Raised in December 1775, the battalion’s first assignment was to New York City and its defense.

Magaw believed he could hold the fort through a siege until December if needed. Although Washington had plans to abandon Fort Washington and actually issued a discretionary order to that effect, Greene successfully lobbied for the fort to be held. Washington acquiesced. Events quickly would conspire to show how folly this decision would be.

As November dawned, the fort’s garrison had risen to about 3,000 soldiers. Tasked with defending the fort were the 3rd Pennsylvania Regiment, 5th Pennsylvania Regiment, Colonel Moses Rawling’s Maryland and Virginia Riflemen, and the Bucks County (Pennsylvania) Militia. Yet, two days into the new month, a desertion occurred that would have severe implications for the Americans. Magaw’s adjutant, William Demont, deserted and showed up within British lines with detailed plans of the fortifications and outlying defenses of Fort Washington. Hugh Percy, the British general whom Demont was led to after entering British lines, sent the intelligence coup up to General Howe, the British army commander. Howe decided on a course of action. He would swing his force toward Fort Washington, south of his current position, instead of pursuing Washington, whom he had just defeated at the Battle of White Plains on October 28.

The order for the British and Hessian forces to move out occurred on November 4 and the plan of battle was devised in the ensuing days. Howe’s plan called for three attacks all approaching Fort Washington from separate directions. To further confound the American defenders, a fourth attack force was ordered to feint an advance as well.

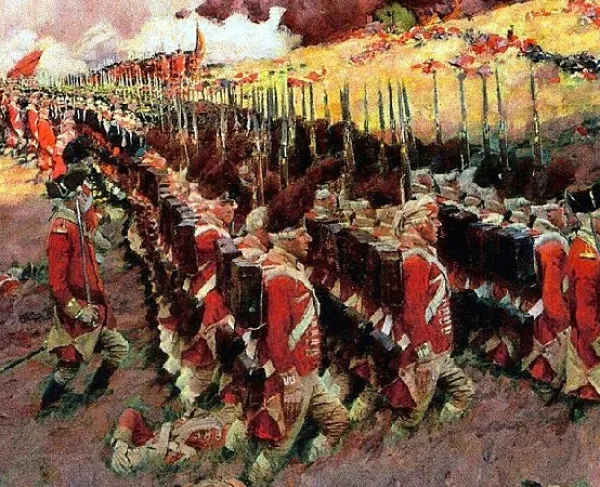

Percy, commanding a brigade of Hessians augmented by a few British battalions was tasked with advancing from the south toward the American positions. From the north, General Wilhelm von Knyphausen’s Hessian attack was planned. Lord Charles Cornwallis, with the 33rd Regiment of Foot and the light infantry under the command of General Edward Mathew, had orders to attack from the east. The aforementioned feint, a landing from the east via the Hudson River and coming on land below the fort, would be the 42nd Highlanders.

Before the elaborate offensive commenced, Howe observed the niceties of 18th century combat by sending in an officer to Fort Washington under a flag of truce on November 15. The message from this subordinate, adjutant general Lieutenant Colonel James Paterson, was received by Colonel Michael Swope of the Pennsylvania Flying Camp. The message as relayed to Magaw was simple: surrender or the entire garrison would be annihilated in the attacks to come.

Magaw’s reply rebuking the proffer of capitulation is as follows:

“If I rightly understand the purport of your message from Gen. Howe communicated to Col. Swope ‘this post to be immediately surrendered or the garrison put to the sword’ –I rather think it a mistake than a settled resolution in General Howe to act a part so unworthy himself and the British nation—But give me leave to assure his excellency that actuated by the most glorious cause that mankind ever fought in, I am determined to defend this post to the very last extremity.”

With that reply, the proverbial die was cast. The next day, November 16, would prove whether the American defenders would resist to “the very last extremity” or if Washington’s abdication to the entreaties of his subordinates to keep the garrison in place would prove fatal.

Before the sun could rise the following morning, Howe’s offensive began. Artillery from both the army and navy began to pound the American positions, sending shot and shell from the south, east, and west. After a delay in crossing the Harlem River, the infantry began their advance around noon. Knyphausen’s advance, initially under heavy fire after landing, quickly charged the American positions, overrunning the defenses before briefly being stopped outside a redoubt defended by Pennsylvania companies. This impediment soon fell though to the determined Hessian advance.

To the left of this advance, other Hessians, under the command of Colonel Johann Rall with accompanying artillery, ran into rifle fire by Maryland and Virginia riflemen under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Moses Rawlings. Using the landscape to their advantage, the American riflemen stifled the Hessian advance, turning back two separate charges.

The pressure continued to mount on the American defenses as Percy’s 3,000 men joined the fray. The defenders braced for the impact but were startled when within 200 yards, Percy stopped his advance. The British general was waiting for the feint by the 42nd Highlanders to come ashore. When the 42nd Highlanders were spotted, the American commander in this sector initially sent 50 men to the shoreline to contest the British. More American reinforcements were then sent when the size of the British landing became known. Although the landing spot was not ideal in terms of topography, the British had landed in a soft spot in the American defenses and veteran leadership quickly sent the men looking for a way up through the hilly terrain. The size of the British advance quickly brushed the American defenders aside.

With the cacophony of rifle and musket fire emanating from the shoreline, Percy restarted his advance, with British artillery softening up the American defenses in the process. When the Americans retreated to a second line, Washington, and a few senior officers, including Greene, Rufus Putnam, and Hugh Mercer were finally convinced to leave New York soil, sailing across the Hudson to Fort Lee. Magaw ordered the men defending against the Highlanders and Percy to withdraw back toward the fort. Luckily for the Americans, the 42nd Highlander’s commander, Colonel Thomas Stirling momentarily held up his advance believing that the entrenchments immediately in his front were held by enemy combatants. Initially, this was not the case, but the delay allowed a small rearguard to organize in time for the rest of the American defenders in this sector to reach the safe confines of Fort Washington.

Now with the southern approaches covered by the British and Hessian enemy, the Maryland and Virginia riflemen to the north finally conceded their positions after facing superior numbers and their weapons fouled up. The American artillery battery in this sector was silenced shortly before the Hessians latest attempt to storm the redoubt. This combination finally proved too much for the American defenders who had resorted to hand-to-hand fighting to try and stave off this last advance.

With the American defenders now bottled up inside the fort, word reached Rall from Howe that he could have the honor to request the surrender of the American force and fortification. As this note arrived in the fort, so did a communique from Washington. The American commander asked Magaw to hold on until nightfall so that the darkness could potentially hide a force evacuation. Magaw wrangled for better terms for capitulation while eschewing Washington’s directive to hold on till nightfall. By 3:00 p.m. Magaw had agreed to the surrender terms and an hour later the American flag was taken down.

In the daylong action, the British suffered 84 killed and 374 wounded. American losses amounted to 59 killed, 96 wounded, and 2,838 captured, most of the rank-and-file destined for the horrible conditions of imprisonment aboard floating prison ships. Historians believe that only 800 men survived their imprisonment when exchanged over eighteen months later. Magaw, as an officer, fared better. After giving his parole he was granted freedom to be at “liberty” around the city. While waiting for his exchange which finally occurred in October 1780, he met Marritje Van Brunt. The two were married in April 1779 and had two children. In addition to the men captured, the British also took possession of thirty artillery pieces and invaluable military supplies that was much needed by their adversary.

Along with the cornucopia of supplies, the British had effectively eliminated the last bastion of American resistance on Manhattan Island. For the Continental army, the loss of manpower coupled with the captured supplies were hard blows to morale and the cause. In addition, the fall of Fort Washington would be one of the lowest points in the military career of Nathanael Greene, who had insisted and persuaded Washington that Fort Washington could be held. Four days later, the Americans would abandon Fort Lee, on the opposite bank of the Hudson River, on the morning of November 20. The fortification was occupied by the British later that same day. Washington’s force would beat a hasty yet hard retreat across New Jersey to the safety of Pennsylvania, beaten and downtrodden but alive to fight another day.

Related Battles

155

458