The Battle of Gaines' Mill: Then & Now

The Civil War Trust recently had the opportunity to walk the Gaines' Mill battlefield with Bobby Kirck, one of the pre-eminent historians of the Seven Days Campaign. Learn more about this important Civil War battle and the state of the battlefield today in our interview below.

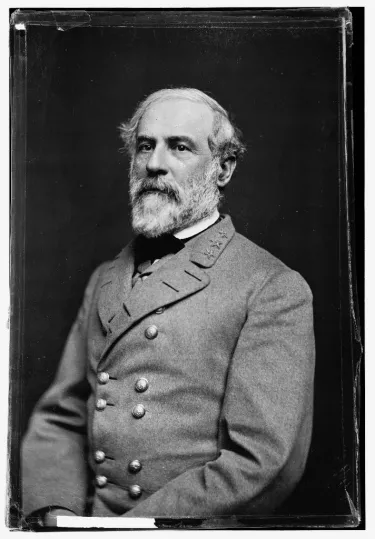

Civil War Trust: The Battle of Gaines’ Mill (June 27, 1862) was Robert E. Lee’s first large battle in command of the Army of Northern Virginia. Help put us into the mindset of Lee before the battle started.

Bobby Krick: When evaluating Lee’s state of mind that morning, it’s important to remind ourselves that he conducted the day’s operations with the notion that the fate of Richmond—his capital city—remained in the balance. We know today that the Union army already was stirring in preparation for a retreat southward to the James River. But Lee did not know that. He had been in command for nearly four weeks, and during that time he had concentrated his energies in preparing for a decisive offensive to save Richmond. He expected that a great battle, of enormous proportions, would be the result. Having manipulated his forces to bring about that battle, at considerable risk to Richmond, he stood ready on the 27th to hurl his army at the Federals to try to win a decisive victory. No doubt he was apprehensive, although the handful of eyewitness accounts to his behavior on June 27 do not report any variation from his usual calm demeanor.

Gaines’ Mill is a rare battlefield where the Confederate forces greatly outnumbered their Union foe. What were Fitz John Porter and the reinforced Union 5th Corps attempting to do? Why were they exposed to this assault?

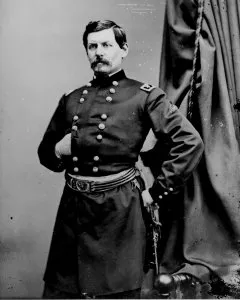

BK: That’s the precise question asked by the Committee on the Conduct of the War when it assembled the following year to examine the Union army’s operations. That committee is not noted for the reasonable tenor of its investigation, but in this instance the question had real merit. At Gaines’s Mill Lee was able to assemble something like 60,000 or 65,000 men and bring them to bear against the 34,000 men under General Porter’s control. The Federals also fought with their backs to the Chickahominy River, which added to their peril. The conventional answer to this question is that General McClellan wanted to buy time for his retreat to get started. Porter’s stand at Gaines’s Mill certainly helped with that. But as McClellan’s legion of detractors pointed out, then and since, it was entirely possible that the same result could have been achieved by withdrawing Porter’s command across the Chickahominy and destroying the bridges, temporarily isolating the majority of Lee’s army on the opposite bank. It probably is fair to say that Gaines’s Mill is a battle that the Federals should not have fought.

Much is made of how Lee’s aggressiveness helped to convince George B. McClellan that he needed to withdraw his army from the Peninsula Campaign that he initiated in March 1862. How did the Battle of Gaines’ Mill factor into McClellan’s thinking?

BK: In my opinion McClellan had no attractive alternatives on June 27. Lee’s boldness—which seemed even more startling when juxtaposed to the calculated languor of his recent predecessor, Joseph E. Johnston—had forced McClellan into choosing from among several equally unpalatable options. By June 27 McClellan’s supply line from the Pamunkey River was beyond salvation, thanks to Lee’s maneuvers. The Union commander really needed to move south to the James River to regroup and to ensure that his army could continue to operate. McClellan’s inability to attack Richmond during the six weeks before Lee’s offensive began created this set of circumstances. I don’t believe that Gaines’s Mill had any direct impact on McClellan’s thinking.

Describe the Confederate attack on June 27th, 1862. Would Lee’s six-division attack make this one of the largest assaults of the Civil War?

BK: It definitely was one of Lee’s largest single attacks of the war, if not the very largest. Where else did he have that many men simultaneously engaged in a tactical offensive? We should guard against envisioning his attack as some smoothly choreographed charge, though. The nature of the ground prevented that, as did extensive confusion among the various Confederate generals. Lee initially believed that A. P. Hill’s division was going to drive the retreating 5th Corps into the lap of Stonewall Jackson’s command, waiting to the east. But the entire orientation of the battle was 90 degrees different than Lee expected, and it took him a very long time to adjust his lines. Eventually Hill attacked, soon joined by Richard Ewell’s division. As more troops entered the battle, the firing line extended to the east and west, and about an hour-and-a-half before sunset Lee had only half of his force engaged. He brought in the final three divisions and attempted to execute an all-out attack, though uneven execution meant that not every available rifleman saw action. Still, it must have been a spectacular sight. At the battle’s climax there were close to 100,000 men engaged in a fierce fight across a two-mile front.

In walking the Gaines’ Mill battlefield you get the sense that the Confederate assault faced difficult terrain and a tough defensive position. Help describe the ground that the Confederates attacked over.

BK: That difficult terrain is one of the key factors in understanding the course of the battle. A Confederate in Stonewall Jackson’s command later commented that the Federal position was the strongest he saw during the war. Visitors to the portion of the battlefield owned by the National Park Service get an excellent understanding of that strength, on the left of the Union line. Porter’s left enjoyed the triple advantage of being perched on a steep hill, with a stream at its base, and open fields of fire to the front. Lee’s men failed to reach even the stream until the very last attack at twilight. In the center of the battlefield dense woods influenced everything. The Federals there relied on those woods to neutralize the Confederate superiority in numbers. On the far Federal right, gentle slopes and sweeping fields of fire helped the defenders. So the battlefield varies from spot to spot, but in every place it was better suited for defense than offense.

Much has been made about Stonewall Jackson’s late arrival on the battlefield. Why was his wing of the army late to the fight? And would his earlier arrival have been a decisive factor?

BK: Jackson was indeed a little tardy, but not decisively so. I think far too much has been made of it, in part because Jackson did so well at so many other places. He was a bit late due to confusion about his route of march. Even that episode is far from clear, with the few available eyewitness sources disagreeing on some of the facts. Apparently Jackson took a shortcut toward New Cold Harbor, initially not realizing that he was supposed to go to Old Cold Harbor. The ensuing delay cost him somewhere between 30 and 90 minutes, depending on whose testimony we accept. There’s not much doubt that had he arrived earlier the whole complicated process of figuring out where the Federals were and realigning to attack them would have started sooner, and would have given Lee some valuable extra time late in the day. But it’s a dangerous business speculating on whether or not Lee could have driven the Union 5th Corps into the river if Jackson had not taken a temporary wrong turn along his march.

The Battle of Gaines’ Mill has one of the most desperate and interesting climaxes of any Civil War battle. Describe the final moments of this great battle.

BK: I suppose the determined men on both sides of the creek watched the setting sun with different feelings. Darkness would effectively end the fighting, and of course Porter’s exhausted men recognized that sunset could provide a means of escape and survival. The Confederates knew that they had a rapidly closing window of opportunity. Lee eventually brought up Whiting’s division and waved forward Longstreet’s division, while off to the east Jackson sent in all of his remaining infantry in a final charge. Porter had no fresh troops to counter the surge and eventually his line gave way in two places—in front of Jackson, and on the far Union left in the face of Whiting’s charge. The Confederate veterans amused themselves for many decades afterward in arguing about who fractured the Union line first. Some of the great drama occurred where a portion of Hood’s brigade swept down the slope, losing heavily, and splashed across the creek. They succeeded where all of their predecessors had failed, and once across the stream they drove a wedge through Porter’s line that could not be mended. There are countless interesting aspects connected to the final action, with an ill-fated Union cavalry charge, the capture of about a dozen cannon, some brief hand-to-hand fighting, and numerous cases of friendly fire in the gloaming. I think all of us who study the Civil War battlefields try to envision the scenes as we stand on the ground, and I’m greatly enamored with an account from an Alabamian who described the chaos as the Union line dissolved at Gaines’s Mill. Some of his comrades, in their anxiety to participate, removed the bayonets from their rifles, dropped the rifles as being too heavy, and continued the charge brandishing only their bayonets in their hands. I often think of that when I’m out on the battlefield.

What is the status of scholarship on Gaines’s Mill? What titles do you recommend for further reading on this topic?

BK: In common with all of the other battles of the Seven Days Campaign, there is no single book on Gaines’s Mill, though apparently there is a new book due for release this spring on Frayser’s Farm/Glendale. Gaines’s Mill never has received the separate treatment it so richly deserves. Until that changes, the best thing to read on the battle would be the several chapters devoted to the battle in Brian Burton’s book on the Seven Days (Extraordinary Circumstances). The other books on the campaign (particularly Sears, To the Gates of Richmond and Dowdey, The Seven Days: The Emergence of Lee) have many merits that make them worth reading, but they are less reliable for details on the actual battles.

What can a visitor to the Gaines’s Mill battlefield see today? And what would you love to see happen to improve this battlefield in the near future?

BK: Despite the comprehensive preservation success elsewhere around Richmond (particularly at the Frayser’s Farm/Glendale battlefield, and at Malvern Hill), that momentum has not carried over to the Gaines’s Mill battlefield. But small preservation triumphs by the Trust and by the Richmond Battlefields Association within the past year have triggered new optimism, and now that the Trust is working on this critical property where Longstreet's division attacked, that missing momentum finally appears to be building, rapidly and wonderfully. A conservative estimate would place the primary battlefield acreage at about 2,000 acres. Richmond National Battlefield Park has owned and interpreted 60 acres there since before World War Two, but that’s been the extent of the public access. So until now something like 2 or 3 percent of the battlefield has been saved, which is especially disappointing for a place important in the history of the contending armies in Virginia. As you might expect, the National Park Service has made maximum use of its 60 acres, covering the ground with trails, interpretive markers, cannon, and anything that would help visitors appreciate the story and the historic landscape. The Watt House, one of the battlefield landmarks, also survives within the National Park. But without access to about 97% of the battlefield, it is close to impossible to provide visitors with any real understanding of what happened there in June 1862. Not surprisingly, my great ambition for Gaines’s Mill is to protect as much of the ground where the desperate action occurred as possible. Although the poor state of preservation at Gaines’s Mill is the bad news, the really encouraging thing is that most of the battlefield is intact. We have not lost it. Nearly all of the battlefield survives in better than average condition, and the potential truly is enormous.

Learn More: The Battle of Gaines' Mill

Robert E.L. Krick is an historian on the staff at Richmond National Battlefield Park. In the 1980's he worked at Custer Battlefield (now Little Bighorn Battlefield) in Montana, and at Manassas National Battlefield. His latest book is Staff Officers in Gray (UNC Press, 2003).

Preserve 838 acres at Gaines’ Mill, Cold Harbor and White Oak Road — land where the nation’s future was decided. Help raise $431,350 to protect this...