By many measures — duration, geographic spread of the fighting, number of troops engaged — it was the biggest battle of the Revolution. The loss at Brandywine cost the fledgling nation its capital, but it earned new respect for troops determined to fight on to ultimate victory.

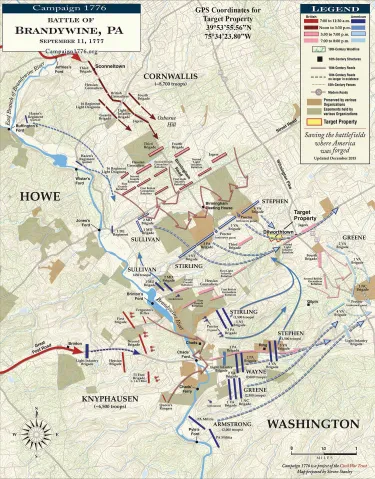

The British victory at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777, led to the army’s capture of Philadelphia — a repeat performance of the tactics used at Long Island the previous year, scoring William Howe’s British army another massive victory over George Washington’s Continental army. Howe’s diversionary column managed to hold Washington’s attention around Chads’s Ford on the Brandywine River, while a massive flanking column conducted a 17-mile march into Washington’s right rear. Washington rushed three divisions to meet the threat upon Birmingham Hill, but two of them were driven away as the fighting rolled into the sector of Major General Adam Stephen’s Virginia division.

While Continental Major General John Sullivan’s division was routing from its position and Major General William Alexander, Lord Stirling’s division was being hard-pressed and beginning to fall back. Stephen’s division on the far right of the American line remained in place atop Birmingham Hill. His two brigades — the 3rd Virginia, under Brigadier General William Woodford, and the 4th Virginia under Brigadier General Charles Scott — were formed on the military crest of the high ground directly above and north of Sandy Hollow, with Woodford on the right side of the division front and Scott on the left. General Stephen later reported to Washington that Scott’s brigade was mostly “Entrenchd to the Chin in the Ditch of a fence Opposite to the Center of the Enemy.”

Advancing against Stephen were, from right to left, the British 1st Light Infantry Battalion, stalled on both sides of the Birmingham Road; the British 2nd Light Infantry Battalion; and on the far left, elements of the Hessian and Anspach jaegers. The Germanic troops had swung well east of Birmingham Meetinghouse but were now bogged down in the low ground between Street Road and Birmingham Hill. Lieutenant Heinrich von Feilitzsch of the Anspach jaegers recalled coming “under heavy canonfire” and coming “upon a swamp which was forged by only a small path in the middle. The situation brought the more disorder among the Jagers, because at the same time we were exposed to enemy small arms fire.” Lieutenant Colonel Ludwig von Wurmb, the jaeger commander, oversaw the advance and described the initial encounter with the American skirmishers a short time earlier: “I saw that the enemy wanted to form for us on a bare hill, so I had them greeted by our two amusettes.” Lieutenant von Feilitzsch noted “the small arms and canonfire became considerably heavier and the smoke darkened everything, yet, it could be noticed several times, that they [Stephen’s division] were making preparations over there to throw us back with bayonets, and because we were not in formation, we did not feel very good about the situation.”

Although the Germanic troops could not effectively use their smaller guns to support their advance, the Americans had no such problem. Situated on good terrain with a commanding view, the battalion guns attached to Stephen’s division did outstanding work defending the position with shell and grapeshot, as did the patriot muskets, which were loaded and fired as fast as humanly possible. The inherent strength of Stephen’s position was undeniable. According to the Jaeger Corps Journal, the Americans were “advantageously posted on a not especially steep height in front of a woods, with the right wing resting on a steep and deep ravine.” The stout defense put up by the Americans likely surprised Lieutenant Richard St. George of the 52nd Foot’s light company, who remembered “a most infernal fire of cannon and musket — smoak — incessant shouting — incline to the right! Incline to the Left! — halt!—charge! … the balls ploughing up the ground. The Trees cracking over ones head, The branches riven by the artillery — The leaves falling as in autumn by grapeshot.” Lieutenant Martin Hunter, another officer in St. George’s light company, agreed with his fellow officer and also took note of the imposing defensive nature of the terrain: “The position the enemy had taken was very strong indeed — very commanding ground, a wood on their rear and flanks, a ravine and strong paling in front.”

One of the jaeger officers fighting on the left wing, Lieutenant Heinrich von Feilitzsch, recalled the “counter-fire from the enemy, especially against us, was the most concentrated.... The enemy had made a good disposition with one height after the other to his rear. He stood fast,” he added, perhaps with grudging respect. Lieutenant Colonel von Wurmb agreed: “We found ourselves 150 paces from their line which was on a height in a woods and we were at the bottom also in a woods, between us was an open field. Here they [Stephen’s main line] fired on us with two cannon with canister and,” continued the Hessian commander, “because of the terrible terrain and the woods, our cannon could not get close enough, and had to remain to the right.” The German light infantrymen, reported one participant, “were engaged for over half an hour, with grape shot and small arms, with a battalion of light infantry. We could not see the 2nd Battalion of Light Infantry because of the terrain, and while we received only a few orders, each commander had to act according to his own best judgment.”

Despite the tactical flexibility of light infantry, the wooded, swampy and sloping terrain in this area, coupled with the heavy American fire, stalled the elite British and Germanic units. The swampy lowlands and thickets had also forced the 4th British Brigade, part of General Charles Lord Cornwallis’s reserve, to swing well west of the Birmingham Road, which in turn denied the light troops their promised support. Unless the jaegers could turn the American right flank, it would be difficult to reach, let alone carry, Stephen’s position. Stirling’s retreat into Sandy Hollow exposed Stephen’s left flank to the surging British troops. Stephen attempted to maintain his position rather than retreat, perhaps to provide as much time as possible for Stirling and Sullivan to withdraw their shattered commands to a safe distance and reform elsewhere.

General Scott’s brigade, holding the left side of Stephen’s division, was but a short distance from the American artillery position that had just been overrun by the British light infantry and grenadiers, some of whom were still pressing against his front. Woodford’s brigade on Scott’s right, meanwhile, was facing a fresh threat from the advancing jaegers and newly placed enemy artillery. After encountering significant obstacles in the form of woods, fences and swampy terrain, the British and Germanic troops finally managed to wheel three guns into an ideal position to enfilade Woodford’s brigade with grapeshot. Two of the guns, three-pounders that were probably attached to the 2nd Battalion of Light Infantry, unlimbered along that unit’s front, with nine companies on their left and another five companies advancing on their right. The third piece, a 12-pounder, set up between the battalions, with the 1st Light Infantry Battalion advancing on its right. From this advantageous position, the British gunners rammed grapeshot down the hot tubes and fired, spraying deadly iron rounds at an oblique angle into Woodford’s line. Whether these metal balls were responsible for taking out the horses of Stephen’s pair of field pieces is unknown, but the animals fell around this time and, when the infantrymen eventually retreated, there was no way to take the invaluable field pieces with them. Woodford, struck in the hand, had also retired down the southern slope to dress his injury.

While the British guns roared, the 2nd Light Infantry Battalion and jaegers, supported by the advance of Brigadier General James Agnew’s 4th British Brigade, pressed Stephen’s front. Five companies from the 2nd Battalion had finally managed to cross the marshy bottomland in front of Birmingham Hill and assault Scott’s brigade on Stephen’s left. “The fire of Musquetry all this time was as Incessant & Tremendous, as ever had been Remember’d,” wrote Lt. Frederick Augustus Wetherall of the 17th Regiment of Foot’s light company, “But the Ardour & Intrepidity of the Troops overcoming every Opposition & pressing on with an Impetuosity not to be resisted.” Ultimately, he continued, “the Rebel Line incapable of further Resistance gave way in every part & fled with the utmost disorder.”

Scott’s men held as long as possible, but Stirling’s withdrawal exposed their left flank. When the patriot guns on the hill ceased firing, the 1st Light Infantry Battalion surged forward to close the distance, overwhelmed the front and engulfed the flank of Scott’s line, which collapsed and retreated down the back of Birmingham Hill into Sandy Hollow and beyond.

While Scott’s brigade was driven back, as late as 6:00 p.m. Woodford’s embattled brigade was still standing firm against the oncoming jaegers and blasts of grapeshot. His men, however, were falling with uncomfortable regularity. Sergeants Noah Taylor and Banks Dudley, both from the 7th Virginia Regiment, were taken out by flying metal. Colonel John Patton’s Additional Continental Regiment lost Private John Stewart with a wound in his left arm and Private Jacob Cook with a shot to his right leg. Captain James Calderwood, whose independent company was attached to the 11th Virginia Regiment, was wounded and died two days after the battle. Eleven years later, his widow applied to the War Department for half-pay.

When the fighting intensified on his right, Lieutenant Colonel von Wurmb “had the call to attack sounded on the half moon [hunting horn], and the Jaegers, with the [Second] battalion of light infantry, stormed up the height.” Despite Woodford’s best efforts, once Scott’s brigade on his left was swept away, it was simply impossible to remain in place for long. The final straw arrived on the opposite flank when von Wurmb’s jaegers struck Woodford’s right; a sergeant and six men worked around the American right to pick off men from the rear. Captain Johann Ewald recorded this tactic in his diary: “During the action Colonel Wurmb fell on the flank of the enemy, and Sergeant [Alexander Wilhelm] Bickell with six jagers moved to his rear, whereupon the entire right wing of the enemy fled to Dilworthtown.” According to another account, Bickell’s movement around Stephen’s right flank put the Germanic troops in a good position to “inaccomodat[e] the enemy for a half hour.” Von Wurmb later wrote with pride that his jaegers “attacked them in God’s Name and drove them from their post.”

“They allowed us to advance till within one hundred and fifty yards of their line,” remembered Lieutenant Martin Hunter of the 52nd Regiment of Foot’s light company, “when they gave us a volley, which we returned, and then immediately charged. They stood the charge till we came to the last paling. Their line then began to break, and a general retreat took place soon after.” An unidentified officer with the 2nd Light Infantry Battalion described the assault from his perspective: “Our army Still gained ground, although they had great Advantig of Ground and ther Canon keep a Constant fire on us. Yet We Ne’er Wass daunted they all gave way.” According to the Jaeger Corps Journal, “the enemy retreated in confusion, abandoning two cannons and an ammunition caisson, which the Light Infantry, because they had attacked on the less steep slope of the height, took possession of.” Lieutenant von Feilitzsch remembered the jaeger line “overpowered the enemy completely; the rebels retreated on all sides, we pursued them until it was 7 o’clock and dark.”

Stephen’s division ended up as scattered and difficult to organize as Sullivan’s broken command. Unlike Sullivan’s men, however, Stephen’s troops were in position and prepared when the British attacked, and acquitted themselves well. This was amply demonstrated when the jaegers reached the summit of the hill and realized that “many dead [Americans] lay to our front.” The 52nd’s Lieutenant Hunter admitted the Americans had “defended [their guns] to the last; indeed, several officers were cut down at the guns. The Americans never fought so well before, and they fought to great advantage.”

As the remnants of Sullivan’s, Stirling’s and Stephen’s divisions retreated to the southeast, they crossed numerous farms — including property recently acquired by Campaign 1776 (now known as the Revolutionary War Trust, a division of the American Battlefield Trust) — just west of Dilworthtown. Ultimately, elements of all three of these divisions were rallied and fought with Nathanael Greene’s division around dusk in the last action of the Battle of Brandywine about a mile south of Dilworthtown.

The two armies continued to maneuver and spar over the next several days, forcing the Continental Congress to abandon Philadelphia and clear it of military supplies. Howe’s army marched into the city, which had been central to the Continental cause, unopposed on September 26, 1777. Though no victory for the patriots, their hard fighting at Brandywine made the British take notice.

Related Battles

1,300

587