Amphibious Warfare: From the Colonial Period to World War II

As one walks into the grand entrance hall of the National World War II Museum, it’s easy to forget amid all the artifacts and imagery that the very building that surrounds you is itself the museum’s greatest treasure. The reason why is tucked away in a corner of that hall – a boat, made of plywood, with a bow plate which doubles as a ramp. That boat is a Higgins Boat, one of only a dozen originals that survive. It is the single most important combat platform developed by the United States in the Second World War, and they were designed and built in the very building where it now sits. But behind the boat lies a story 150 years in the making: the history of amphibious warfare in the United States.

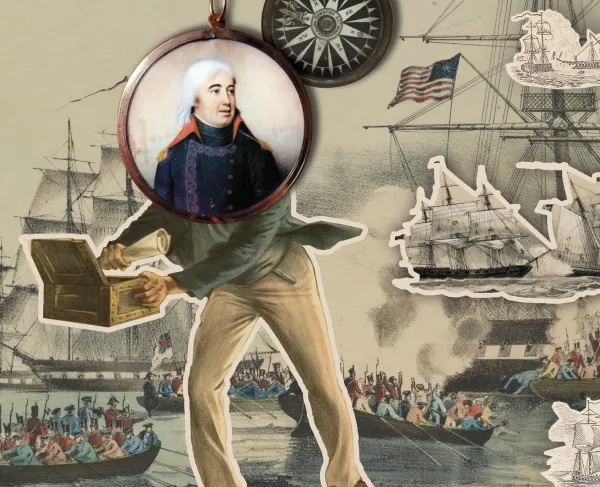

Months before America declared her independence, United States Marines carried out the infant nation’s first amphibious assault. Samuel Nicholas, the founder of the Marine Corps, and a detachment of Marines rowed in small boats onto the beaches of Nassau, in the British-owned Bahamas Islands. The raiders captured 38 casks of gunpowder along with other military supplies. This inaugural operation was plagued with poor luck, bad decisions, and lack of training, but did prove to the British that their Caribbean possessions, far more profitable than those in North America, were within reach of the United States military. Many British troops were thus detailed to defend those islands who might otherwise have fought against American troops at home.

Far more famous was America’s second amphibious operation. On the night of Christmas Eve 1776, George Washington and the Continental Army crossed the icy Delaware River, again in rowboats, and attacked the Hessian garrison of Trenton, New Jersey. The passage over the river was no small feat. Washington had to transport four to six-thousand troops across the Delaware, along with heavy and oddly shaped cannons and their carriages. Troops dodged ice floes which threatened to smash into the hulls of the boats. Nevertheless, in a matter of hours Washington’s army arrived in New Jersey with the loss of only five men.

During the War of 1812 American troops crossed Lake Ontario and Lake Erie into Canada to strike at British forces there. Far more successful, however, were British amphibious attacks against American coastal cities, the most spectacular of which was the British capture of Washington D.C. There, while the British army landed on the coast and marched on the city, the British fleet sailed up the Potomac River. The land force defeated the American army at Bladensburg while the fleet’s mere presence convinced the defenders of the badly outgunned Fort Washington to spike their guns and leave without firing a shot. Washington fell to British forces, who burned the White House and Capitol. When the British afterward attempted to capture Baltimore by the same method, the Americans were prepared. The British army was defeated at the Battle of North Point while the fleet unsuccessfully bombarded Fort McHenry, guarding the entrance to the harbor. Immediately before the end of the war another British amphibious force landed in Louisiana and marched on New Orleans. The resulting Battle of New Orleans on the Chalmette Plantation ended with a crushing British defeat. As a result of the War of 1812, the United States realized the need for extensive coastal fortifications and set about constructing a series of forts guarding its major ports.

During the Civil War many of these forts saw combat as Union troops landed at points along the Confederate coast to capture these outposts and close Confederate Harbors to commerce. The Civil War also saw one of history’s first contested amphibious operations. In December, 1862, Ambrose Burnside ordered a landing party to secure a foothold in Fredericksburg, Virginia, across the Rappahannock River from where the Union army was encamped. Under fire from Confederate sharpshooters who were holed up in basement windows and behind barricades in the town, Union troops used pontoon boats to row across the river and land on the far side. Intense street fighting followed, as Union troops sought to expand the bridgehead and force the Confederates out of the town. After hours of fighting the Union secured the town and its engineers were able to complete several pontoon bridges which allowed Burnside’s army to cross the river.

Eighty years later, during World War II, the United States faced the prospect of fighting across two oceans simultaneously. To defeat the Axis Powers, the US would need to launch amphibious operations at a scale and frequency never before seen in military history. To do this the military needed hundreds of ships, but also many thousands of landing craft to get the troops ashore. Rowboats would not do. The British had learned that hard lesson on the Gallipoli Peninsula twenty years earlier. Enter Andrew Higgins, an American inventor, who presented the Army with a flat-bottomed boat made of cheap and easy-to-produce plywood. The boat had a metal ramp on the front, allowing troops to easily disembark, which also served as a ballistic shield during transport. The flat bottom allowed it to go all the way to shore and beach itself, saving the troops from a swim. The military awarded Higgins a contract to produce as many of these boats, dubbed “Higgins Boats”, as he could. Higgins constructed a factory in New Orleans where over the course of the war he built over 20,000 of them. This enormous capacity allowed the US military to conduct massive amphibious assaults in both Europe and the Pacific simultaneously. For example, in June 1944, Higgins Boats landed half a million men in Normandy, France, while also putting 100,000 men ashore on Saipan, in the Mariana Islands, quite literally on the other side of the world. The National World War II Museum now occupies the same factory building where these boats were manufactured, a critical piece of the eventual Allied victory.