10 Facts: Glendale

The Battle of Glendale was marked by uncommon valor but marred by command mistakes that would have long-lasting repercussions. Please consider these 10 facts in order to expand your knowledge of this pivotal struggle on the Virginia Peninsula.

Fact #1: The Battle of Glendale was the fifth battle of the Seven Days’ Battles.

On June 26, 1862, after an inexorable advance across the Virginia Peninsula, the Union Army of the Potomac was less than a day’s march away from the Confederate capital of Richmond.

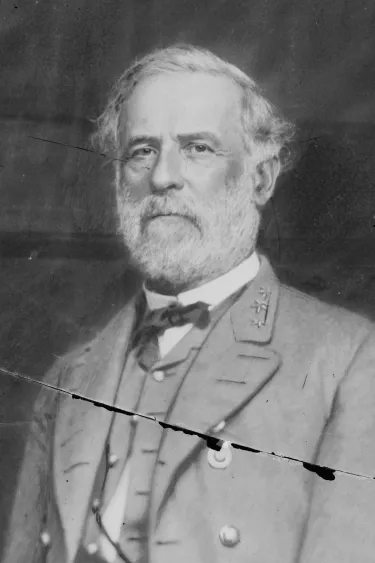

Then, for four days, the Confederates hurled themselves at successive Union positions in a series of deadly close-quarters battles in the swampy forests around Richmond. The June 27 battle of Gaines' Mill severed Union commander General George McClellan's line of communications with Washington, prompting him to order a full-scale retreat towards Harrison’s Landing on the James River. On June 30, Robert E. Lee, newly placed in command of the Confederate army, launched his next major attack at Glendale.

Fact #2: Glendale was Robert E. Lee's best chance to seriously damage the Union army during the Seven Days.

To reach Harrison’s Landing, two-thirds of the Union army, some 62,000 men, would have to pass through the crossroads hamlet of Glendale on June 30. Robert E. Lee was poised to strike at that crossroads with 71,000 Confederates. He planned to fight a battle in which portions of his army would pin down Union forces north and south of the crossroads while his main attack broke through the weakened center.

The Union units around Glendale were disorganized and demoralized. They fought on June 30 with more courage than cohesion. The breakdown of Lee's complex battle plan, as happened so often during the Seven Days, led to a violent struggle that severely bloodied the Federals but failed to prevent their retreat. Had Lee seized the crossroads, the Union army would have been split in half, exposed in tangled enemy country, and in danger of complete destruction. His failure left the Union escape largely assured.

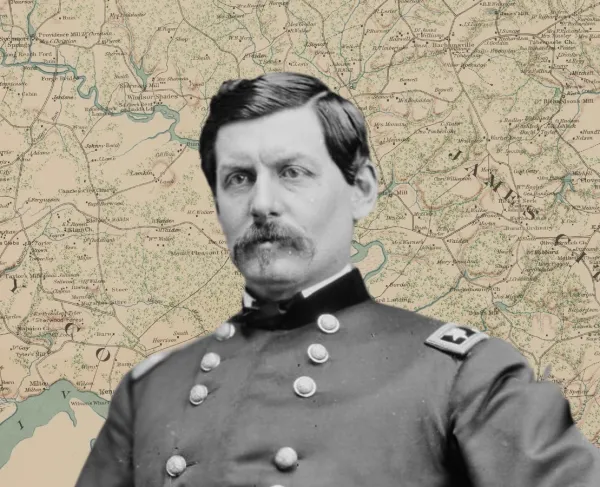

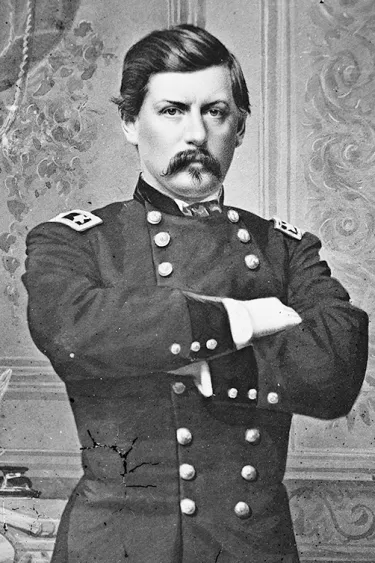

Fact #3: Union General George B. McClellan spent the battle aboard the gunboat U.S.S. Galena.

George B. McClellan, or “Little Mac,” had come to the Virginia Peninsula hoping to fight an American Waterloo, a huge and war-ending battle in which he would be the hero. The immense casualties of the engagements so far, however, and the reversal of the campaign that had held such promise just days earlier, left him thoroughly demoralized. On June 30, the Union army was strung out on the narrow roads leading to Harrison’s Landing with each corps commander managing his own withdrawal and planning his own battle. Everyone in the clearing around the hamlet knew that “the whole woods were full of rebels.”

Where was McClellan? He had ridden ahead of the army to board the gunboat U.S.S. Galena on the James River. The Galena then steamed upriver while McClellan ate dinner and drank wine.

The Union army at Glendale suffered greatly from not having a central figure in command. Since McClellan failed to plan or supervise the army’s retreat, the units around Glendale were jumbled together from different commands without the necessary command presence to respond effectively to enemy movements. The Union men deployed in a jagged, disjointed line, the flank of one unit not joined smoothly to the flank of another, resulting in an area full of "bite-sized" portions of the army. When Lee’s men emerged from the woods, these isolated units would be dangerously exposed, demanding either a breakneck withdrawal or immediate support.

Fact #4: More than one-third of the Confederate army failed to reach the Glendale battlefield.

Lee’s plan for June 30 called for Stonewall Jackson, just returned from an exhausting but triumphant campaign in the Shenandoah Valley, to open the battle by moving his force against the Federal right flank, protected by men of General William B. Franklin’s Sixth Corps, across the White Oak Swamp. This attack was not designed to gain ground, but rather to keep men and attention fixed on that sector of the field while the main effort came against the Union center. Instead, finding the swamp largely impassable and covered by enemy artillery, Jackson chose not to advance his men. It became clear to his subordinates that the pious Virginian was all but insensible with fatigue. By failing to sufficiently threaten his objective, Union officers in the area were able to dispatch nearly 12,000 soldiers to reinforce the center. That night, Jackson fell asleep while chewing his dinner.

The timid General Benjamin Huger (pronounced "You-Jee") was slated to take the opening shot at the Union center but was stymied by a roadblock of felled trees along his avenue of approach. Huger elected to cut a new road through the trees rather than detail men to remove the roadblock. General Theophilus Holmes, moving against the extreme Union left at Malvern Hill, ended up on the losing end of an artillery duel and chose not to move his infantry forward. Though they were not a major factor in Lee's plan, General John B. Magruder's troops were blocked by Holmes immobile force and, thus, unable to participate in the battle.

These failures by Lee’s generals left most of the Union force uncommitted and able to transfer reinforcements to threatened sectors. With considerable frustration, Lee sent General James Longstreet’s division directly toward the Glendale crossroads shortly before 5:00 p.m. Although Lee had planned to bring more than 70,000 men to battle at Glendale, 25,000 were neutralized by failures amongst the Confederate leadership.

Fact #5: The Pennsylvania Reserves—exhausted from previous battles—found themselves at the center of the action.

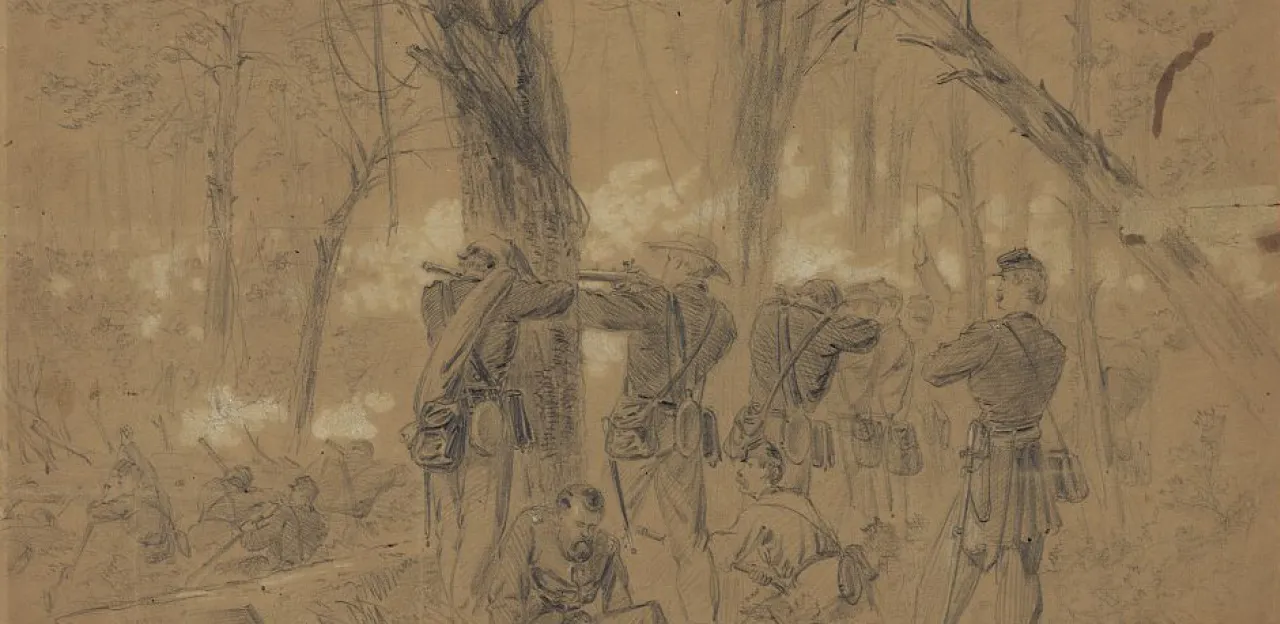

Pennsylvania Reserves, a Union infantry division commanded by General George McCall, had received their first introduction to pitched combat at the June 26 Battle of Mechanicsville, where they were forced to withdraw. On June 27, at Gaines’ Mill, they were dislodged by a grueling day of Confederate attacks and also suffered the capture of one of their best general officers, John Reynolds. Now, at Glendale, the weary Pennsylvanians were in the center of the Union battle line, staring into the dense woods to the west that concealed the Confederate army.

Around 5:00 p.m., Longstreet’s division swept out of the trees with a rebel yell. General James Kemper’s Virginia brigade, drove in the left-most portion of the Pennsylvanian's skirmishers, captured Captain Otto Diederichs’s battery, seized the Whitlock farmhouse, and turned the Pennsylvanians’ left flank. Another Confederate brigade under General Micah Jenkins made a dash for the six cannons of Captain James Cooper's battery in the center of the Union line. Fighting spilled over to the Pennsylvanians' right flank, held by General George Meade’s brigade, and Captain Alanson Randol’s six-gun battery. The Pennsylvanians rushed to defend their guns, becoming embroiled in a close range firefight which one witness described as involving "more actual bayonet, & butt of gun, melee fighting than any other occasion I know of in the war."

Fierce hand-to-hand fighting swept back and forth across the field until both sides withdrew, bloodied and exhausted, into their respective wood lines. The guns were abandoned. Meade was shot twice. George McCall was captured. Both sides rushed reinforcements to the vortex at the center.

Fact #6: Seventeen year-old Private Benjamin Levy of the 1st New York Infantry won the Medal of Honor at the Glendale crossroads.

Benjamin Levy, a native of New York City, had enlisted in the Union army at the age of sixteen. Still technically ineligible, though the rule was commonly ignored, Levy was assigned to the musician corps of the 1st New York Infantry as a drummer boy.

On June 30, 1862, he was in a tent just north and east of the Glendale crossroads. As the roar of musketry from the first line started to reach a crescendo, Levy chose to act. Leaving behind his drum and borrowing a sick comrade’s musket, the young soldier rushed to join the regimental battle line as it moved into the twilight struggle at the Glendale crossroads. Confederate bullets quickly decimated the regiment’s color guard, causing the New Yorkers to waver. Seeing the crisis unfold, Levy moved to the front of the formation and raised the battle flags once again. The line steadied around the former drummer boy and, with the help of reinforcements, the Confederates were eventually repulsed. Levy is the first person of documented Jewish faith to win the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Fact #7: Union general Phil Kearny was nearly shot or captured when he wandered into a Confederate skirmish line at Glendale.

Phil Kearny, a one-armed Army regular and one of the most capable generals in the Army of the Potomac, directed the Union fight north of the Glendale crossroads. The terrain in the sector was tangled and densely forested. During a lull in the battle, Kearny ventured too far while conducting reconnaissance in the Confederate tree line. This became evident when a young officer approached him, asking "What shall I do next, sir?" Kearny recognized the officer as a Confederate, but the recognition was apparently not mutual. Looking around, Kearny saw that the woods were full of enemy skirmishers.

"Do, damn you, why do what you have always been told to do!" Kearny snapped back. The officer, mortified to have received such condemnation from a superior, did not question Kearny further as the quick-thinking New Jerseyan slipped back to his own lines.

After the Seven Days’ Battles came to an end, Washington was abuzz with rumor that Kearny would be tapped to replace McClellan. The whisperers were silenced, however, on September 1, 1862, when Kearny was shot dead at the Battle of Chantilly when a similar reconnaissance encounter went awry.

Fact #8: Federal reinforcements saved the Army of Potomac from disaster.

The savagery of the opening battle for the Glendale crossroads left both sides shaken and exhausted. With the issue very much in doubt, Union and Confederate reinforcements hurried toward the fray. More Confederates arrived first, in a formidable second line composed of some 10,000 men from the Longstreet’s and A.P. Hill’s divisions. Sweeping into the battered Union elements left over from the first phase of the battle, the Southerners were on the verge of a breakthrough when fresh Union troops began to arrive.

These were men redeployed from the sectors left unthreatened by Benjamin Huger and Stonewall Jackson, more than 12,000 in all. They arrived at the crossroads at the critical moment in the battle and refilled the fractured Union line. The Confederate effort stalled as the weary attackers went to ground and exchanged volleys in the waning light. Engulfing darkness put an end to the fighting soon afterwards. Despite their early success, the Confederates had been prevented from interdicting the vital crossroads by the timely shift of reinforcements that, if Lee’s plan had worked, would have been pinned down by Jackson and Huger on the flanks.

Fact #9: The missed opportunities at Glendale led to a bloody frontal assault at the Battle of Malvern Hill the next day.

With the roads secure, Union troops continued to retreat towards Harrison’s Landing. The landing was covered from the west and north by Malvern Hill, a commanding position where McClellan placed most of his army on July 1. With one last chance to decisively defeat their northern foes, the Confederate infantry charged the heights and broke up violently against the Union line.

If the Battle of Glendale had gone differently, perhaps more according to plan, the fruitless charges into massed artillery need not have happened. Writing after the war, Confederate artillery chief Edward Porter Alexander declared that “on two occasions in the four years, we were within reach of military successes so great that we might have hoped to end the war with our independence. ... The first was at Bull Run [in] July 1861 ... This [second] chance of June 30, 1862 impresses me as the best of all.”

Fact #10: The American Battlefield Trust has spearheaded the preservation of hundreds of acres at the Glendale battlefield.

In the words of historian Bobby Krick, "the preservation success at Glendale defies comparison." Starting from approximately one acre of preserved land, the Civil War Trust and its members have saved almost the entirety of the battlefield, encompassing most of the major areas of fighting. This work is supplemented by hundreds more contiguous acres preserved by the American Battlefield Trust at Malvern Hill.

Learn More: Seven Days Battles

We have a chance to save these critical pieces of history at Gaines' Mill, Cold Harbor, and Appomattox Court House for just a fraction of their full...

Related Battles

6,800

8,700

3,797

3,673

2,100

5,600