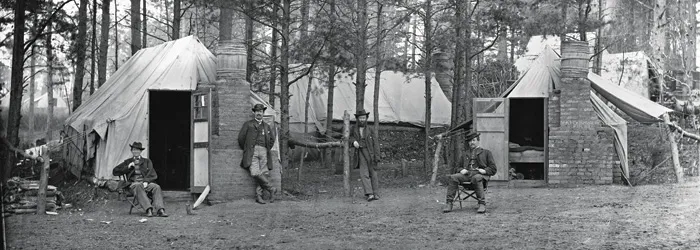

Brandy Station, Va. Quarters of Capt. Harry Clinton, quartermaster, Provost Guard

By Gary Helm

Only a tiny fraction of any soldier’s time was spent in front line combat. Instead, the vast majority of his existence revolved around the monotonous routines of camp life, which presented its own set of struggles and hardships.

Once in the ranks, military life turned out to be far different than what the majority of Civil War soldiers had expected. Patriotic zeal blinded most of these volunteers to the realities and hardships they were signing up to experience. The passage of several generations had muted the country’s memory of the deprivations of the American Revolution. Few had participated in the war with Mexico, which left a popular legacy of glorious victory. Certainly, argued the conventional wisdom, this sectional crisis would be resolved in a few short, painless months.

Volunteers viewed the battlefield as a great stage upon which they would either “secure their liberty” or “save the Union.” While they acknowledged that losses would occur, no one envisioned their potential demise in any but heroic circumstances, but four years of the daily struggle to survive in military camps would prove otherwise. Twice as many Civil War soldiers succumbed to death from disease as from bullets, shells and bayonets. By varying estimates, between 400,000 and 500,000 soldiers lost their lives on this less gallant of stages. What was the basis of this noncombat struggle, and how did the common soldier cope?

During the fair-weather campaign season, soldiers could expect to be engaged in battle one day out of 30. Their remaining days were filled with almost interminable drilling, punctuated with spells of entertainment in the form of music, cards and other forms of gambling. The arrival of newspapers or mail from home — whether letters or a care package — in camp was always cause for celebration. Despite such diversions, much time was still left for exposure to the noncombatant foes of poor shelter, unhealthy food, and a lack of hygiene, resulting in waves of sickness and disease.

After the first months of the war, the shelter half, or “dog tent,” became the most practical means of overnight shelter. While portable and lightweight, shelter halves provided minimal protection for their two inhabitants. Sgt. Austin C. Stearns of the 13th Massachusetts described his shelter as “simply a piece of cloth about six feet square with a row of buttons and button holes on three sides; two men pitched together by buttoning their pieces together and getting two sticks with a crotch at one end and one to go across at the top and then placing their cloth over it and pinning it down tight.” To protect the soldier from the damp ground, a tarred or rubberized blanket could be used. A stout wool blanket kept the chill off. Unfortunately, many soldiers discarded these heavy items on a long march or when entering combat, and lived (or died) to regret it when the weather changed. As the war moved forward, an exhausted soldier often merely lay on his blanket at night in an effort to simplify his life and maximize periods of rest. Such protracted exposure to the elements boded ill for his life expectancy.

Rations on the march varied from plentiful to scarce. On paper, the Union army enjoyed the best rations of any army in history up to that time, but logistical difficulties inherent in feeding armies of tens of thousands resulted in occasional shortages. The Confederacy, while fighting on predominately “home turf,” often found it difficult to consistently deliver full rations to its troops on the march, largely due to procurement and transportation problems.

The full Union marching ration consisted of one pound of hard bread (the infamous hardtack), three-quarters of a pound of salted pork or one-and-a-quarter pound of fresh meat, along with coffee, sugar and salt allotments. At the beginning of the war, the Confederacy adopted the Union ration, but reduced it by 1862. Fresh meat and coffee became increasingly scarce. As fresh fruits and vegetables disappeared from military diets, soldiers’ immune systems deteriorated and vitamin deficiency diseases such as scurvy proliferated. The Union army responded by issuing desiccated vegetables. As described by Corp. Joseph Van Nest of the 101st Ohio, these delicacies consisted of “a combination of corn husks, tomato skins, carrots and other kinds of vegetables too numerous to mention.” This bounty had been dried and compressed into a sheet or block and, when boiled, expanded to many times its previous size. While denigrated as “desecrated vegetables” by the boys in blue, they consumed them with alacrity as a variation in an otherwise bland diet. Unfortunately, unbeknownst to the culinary science of the era, most of the needed vitamins disappeared during processing.

Confederate soldiers usually had to forage for fresh vegetables. During the deprivations of the 1864 Atlanta Campaign, one Johnny Reb wrote, “Our men get a vegetable diet by cooking up polk, potato tops, May pop vines, kurlip weed, lambs quarter, thistle and a hundred kind of weeds I always thought poison. I thought it trash…but the boys call it ‘long forage’…” On the march, “foraging” — a convenient euphemism for theft — would be employed by both sides in an attempt to improve the daily diet. Despite orders to the contrary, some Confederates liberally practiced this thievery during their forays into the North and even when marching and camping in friendly territory.

The commissary took a back seat on the march to the needs of the ordinance department, but still trumped the quartermaster, whose top priority was to provide forage for draft animals, not replacing uniform components. Threadbare patriots consequently appeared, particularly in the Confederate armies, and the “battlefield requisition” became a prime means of supply for the South. As Sgt. John Worsham noted at the end of the war:

“Nearly all equipment in the Army of Northern Virginia were articles captured from the Yankees…. Most of the blankets were those marked ‘US,” and also the rubber blankets or cloths. The very clothing that the men wore was mostly captured, for we were allowed to wear their pants, underclothing and overcoats. As for myself, I purchased only one hat, one pair of shoes, and one jacket after 1861.”

Soldiers North and South also shared in the infestation of body lice in their clothing and bedding. Due to constant outdoor living, often under poor sanitary conditions, the “grey back vermin” became a visible manifestation of all of the invisible bacteria and germs whose presence was unknown to mid-19th-century science.

The seasonal movement to permanent winter camps would simultaneously improve and harm the physical condition of the Civil War soldier. While the men remained in one place, the supply chain of wagons and railroads caught up to their daily needs. Union logisticians employed their superior resources in overcoming commissary and quartermaster problems, but the Confederates also managed to supply their men in winter camp under more challenging conditions.

Periodic shortages did exist, but were vividly remembered by the Southerners. Both sides shared the difficulties that emerged from remaining in one place for an extended period of time. The majority of soldiers, being from rural backgrounds, had not been exposed to such a wide cross section of the human population and its communicable diseases. When accumulated in camps of tens of thousands, soldiers without natural immunities would succumb to the likes of measles and chickenpox. Those same large numbers, residing in one spot for more than a month, caused horrendous situations in relation to sanitation. The use of "sink pits" as latrine mechanisms ultimately led to the presence of human fecal bacteria in the water supply. That water supply, in many instances, did not need much help in the area of contamination. Swift running, clear water would be the exception more often than the rule. These conditions created the greatest killer of the war: amoebic and bacterial dysentery.

Whimsically called a case of the “quickstep,” dysentery did more damage than the infernal killing creations of man. The creation of penicillin and other antibiotics was still decades away, leaving medical staffs of the Civil War few tools to combat the war’s greatest killer. By the end of the war, the Union Sanitary and Christian Commissions made great strides in improving camp hygiene and clean water. The Confederacy had nothing on such a scale, although experience also improved camp conditions for the boys in gray.

After four long years of war, the military encampments had taken their toll. Although the 2:1 rate of death from disease over combat may seem alarming to us today, it represented a significant improvement from earlier conflicts, like the American Revolution and Napoleonic Wars, when that number was closer to 5:1. Not until World War II did the number of battle casualties approach the losses from disease.