Civil War Irregular Operations

In his 1996 book SPEC OPS: Case Studies in Special Operations Warfare: Theory and Practice, Adm. William McRaven crafted a definition of the genre tailored to his analysis of undertakings that predated the official formation of modern Special Operations Forces. By his reckoning, Special Operations are those “conducted by forces specially trained, equipped, and supported for a specific target whose destruction, elimination, or rescue (in the case of hostages) is a political or military objective.”

Many famed Civil War “irregular operations” slot easily into this framework — unconventional warfare, like partisan units or sabotage, direct raids and ambushes and special reconnaissance missions. A number of the American Battlefield Trust’s staff members, all passionate students of history, jumped at the chance to share their own choices for the most fascinating irregular operations of that conflict.

David Duncan, President of the American Battlefield Trust, describes his selection:

Under the cover of night and shrouded by inclement weather, Lt. Col. John Mosby — aptly nicknamed “The Gray Ghost of the Confederacy” — launched a legendary raid over the Northern Virginia terrain that I now call home. On his side were all the ingredients that make a Special Operation successful: good intelligence, practice and the element of surprise.

Mosby’s force was filled with resourceful horsemen who executed their work with precision and speed, and then stealthily reintegrated back into civilian life following each mission. After a string of successful raids in early 1863, Mosby’s notoriety as a ranger — and Federal frustration — was on the rise. Unable to catch him, Sir Percy Wynham, a flamboyant Englishman in command of regiment of New Jersey cavalry in the region, resorted to impugning Mosby’s honor, calling his men “horse thieves” and setting into motion one of the Civil War’s most fascinating irregular operations.

In response to this insult, Mosby set out to capture Wynham and upend Union forces in Fairfax. He gathered intelligence from civilians and Union prisoners, studied the county’s “deer and rabbit” pathways with one of his local troopers and obtained details of picket lines from a Yankee deserter. The stage was set for the night of March 8–9, 1863.

The success of the operation depended on its security, given that Mosby’s reputation for raiding made him a high-profile target. Only after crossing enemy lines did Mosby reveal the full extent of the plan to his 29 troopers. At 2:00 a.m., in the rain, Mosby’s men infiltrated the hamlet of Fairfax Courthouse and began taking prisoners and horses. As they moved toward the Fairfax Station in search of Wynham, they learned that he had returned to Washington, and that Brig. Gen. Edwin Stoughton, the commander of the Vermont Infantry Brigade, was sleeping in a house down the street.

Mosby adjusted on the fly and utilized the element of surprise to break in and capture the sleeping Stoughton. When they slipped back through Union lines in the pre-dawn gloom, Mosby’s Rangers brought with them one brigadier general, two captains, 30 enlisted men and 58 horses. Only a single shot had been fired the whole night, and not a soul was harmed.

Paul Coussan, Deputy Director of Government Relations:

A few years ago, on one of my excursions to Georgia for the Trust, I decided to track down the series of pocket parks built in the 1930s tracing the Union army’s march from Chattanooga to Atlanta. Authorized by the secretary of the interior in 1944, the Atlanta Campaign National Historic Site (NHS) is a defunct, never fully realized national park unit that has been largely forgotten as a means of highlighting and connecting the series of actions in 1864 that culminated in the capture of Atlanta by Sherman’s army. Small parks along the “Dixie Highway” in Ringgold, Rocky Face Ridge, Resaca, Cassville and New Hope Church are all that remain of this early effort to interpret one of the more decisive actions of the entire Civil War.

Not far from the first stop in Ringgold, just south of Chattanooga, is a small, unassuming marker along the side of a railroad track — a weathered granite monument, engraved with the word “GENERAL,” the red paint in each letter fading away. Below the carving is a bronze plaque that reads, in part, “This tablet marks the spot at which the Locomotive ‘GENERAL’ was abandoned by Andrews’ Raiders, afternoon of April 12, 1862.” Two years before the Union army swung through here, northern Georgia was already a hotbed of activity, as Confederate forces secured and defended all major railroad lines between the cities of Chattanooga and Atlanta. Several attempts were made by Union spies to cut the rail lines and sever travel and communications between the cities, and one came close to succeeding.

This most well-known raid was led by a civilian, James Andrews, who commandeered the locomotive “General” near Atlanta, and hurtled north with a band of raiders, cutting a trail of destruction in their wake. They severed communication wires and tore up railroads, but the steep grade of the tracks slowed the locomotive and allowed another engine, “Texas,” to pursue them. As the Texas closed in, Andrews and his raiders were unable to sever the lines and destroy the rails behind them, and were forced to abandon the locomotive outside Ringgold, escaping to the surrounding woods. Eventually, Confederate forces tracked all of them, and tried, convicted and executed most of them, including Andrews. After the war, the raiders were buried at Chattanooga National Cemetery; a small monument capped with a bronze model of “General” stands watch over their headstones in a small section of the cemetery.

The heroism of the raiders became legendary, and many received the Medal of Honor (as a civilian, Andrews was not eligible.) Audiences of the 20th century became familiar with the raid with the Disney film The Great Locomotive Chase.

If you plan to track down the many battlefields saved by the Trust that make up the Atlanta Campaign, or you want to stop by the pocket parks of the former Atlanta Campaign NHS, the “General” monument should definitely be on your list. The marker is not far from Ringgold, but be careful if you want to try to visit! There is a small pull-off in front of the marker, barely large enough for one vehicle, and there are no signs alerting drivers to the historic marker.

Jim Campi, Chief Policy Officer:

The leader of an operation whose target is a steam-powered ironclad gunboat ram ought not to be faint of heart. And indeed, Union Lt. William Cushing was bold in the extreme, submitting plans to take on the Confederate ironclad that was dominating the Roanoke River during the Civil War.

The CSS Albemarle played a significant role in the Confederate capture of Plymouth, N.C., in the spring of 1864, managing to sink the Union’s USS Southfield, and severely damage the USS Miami, killing Cushing’s dear friend Lt. Commander Charles Flusser in the process. From a strategic standpoint, capturing or sinking the dangerous Albemarle was crucial for the Union, but for Cushing, it was personal.

Many elements had to come together for Cushing’s envisioned operation, starting with specialized equipment and a committed crew. Cushing got the idea for a portable torpedo from the Confederate attack on the USS Cairo near Vicksburg in 1862. The boat Cushing launched his attack on was armed as a spar torpedo launch: One lanyard had control over the wooden spar, which could lower the device into the water, another set off the cannon and a third detonated the torpedo. All those who undertook the mission were volunteers, and Cushing instructed them not to hope for return, ensuring full commitment to the outcome of the operation.

On the night of October 27–28, 1864, Cushing and company on the spar launch crawled up the Roanoke toward Plymouth. Increasing obstacles arose as they approached the Albemarle. First, a dog barked, waking and alerting the Confederate sentry. Then, upon approach to the Albemarle, the clandestine crew found a barrier of logs protecting the ironclad’s hull from torpedo attack.

But Cushing would not stop now after coming this far — the only way was forward, pushing past the logs even as the fully roused Confederates opened fire. Through a swarm of bullets, Cushing was able to keep a tight grip on the torpedo’s controls and lower the boom holding it into the water alongside the Albemarle’s hull. He pulled the lanyard, setting off both the cannon and the torpedo in a massive explosion that knocked all the Union soldiers into the water.

Cushing made it to the riverbank, where he hid from Confederate search parties. After daylight, he stole a skiff and, using his arms instead of oars, made the perilous journey downriver to Union lines. The rest of his own command were not so lucky: Two men drowned and 11 were captured — only one other raider escaped. But the mission had been successful! Courtesy of a hole “big enough to drive a wagon in,” the CSS Albemarle sat at the bottom of the river.

Catherine Noyes, Liberty Trail Program Director:

As a native of South Carolina, I’ve long been interested in the story of the H. L. Hunley. I remember hearing the news when the mysterious sunken submarine was discovered off the shores of Charleston in 1995. Headlines came again in 2000, when it was retrieved from the water and moved to the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, and intermittently since, as various discoveries about the ship and her fate have been uncovered — especially as members of the lost crew were identified and laid to rest.

Designed and built in Mobile, Ala., and sent to Charleston to combat the Union blockade, the Hunley was the first submarine to sink an enemy ship in combat. Unlike modern submarines that can launch missiles great distances, the Hunley was essentially a submerged spar torpedo boat — it had to deliver its single explosive right up to the target and ram it home. The Hunley had no on-board engine, instead, it was powered manually by a crew of eight men, all volunteers. Serving inside the 40-foot, iron-hulled vessel was dangerous — she sank twice on training exercises, losing a total of 13 sailors. Despite the casualties, the Hunley’s method showed promise, and a mission was organized.

On the evening of February 17, 1864, the Hunley attacked the USS Housatonic outside Charleston Harbor. Union sailors sighted her approach and fired on the submarine, but their shots were deflected by the metal hull. The Hunley reached its target and detonated its spar torpedo, and the Housatonic sank in less than 15 minutes. But the triumphant Hunley never re-emerged from beneath the waves, and the secrets of her successful run were lost along with all hands.

When the Hunley was rediscovered 130 years later, those secrets slowly began to come to light. Forensic anthropology revealed the identities of the lost crew, and blast analysis has offered speculation about the damage sustained by the ship and the crew’s cause of death. Perhaps the most poignant story to come out of the Hunley involves its captain, Lt. George Dixon. Fighting at Shiloh in 1862, Dixon was struck in the hip by a ball, a wound that might have been mortal had the round not been deflected by a gold coin in his pocket. Alongside the remains found in the wreckage was a deformed $20 gold coin engraved with the lines “Shiloh April 6, 1862/ My life Preserver/ G.E.D.”

Tracey McIntyre, Program Assistant:

On the night of June 1, 1863, three Union gunboats left Beaufort, S.C. Their mission: to remove mines from the Combahee River, destroy supplies destined for Confederate troops stored at nearby plantations and rescue and recruit enslaved African Americans along the route. This raid was unique among the many conducted during the Civil War for two reasons. Not only was it led by a woman, but she was an African American who had been enslaved.

Harriet Tubman escaped slavery in 1849 and gained renown conducting raids of her native state of Maryland to bring others to freedom. By 1862, she had left her work on the Underground Railroad and volunteered as a teacher, nurse and spy in Union-occupied Hilton Head, S.C. From those who had escaped from plantations in the area, Tubman gained important information about the location of mines that had been placed in the Combahee River by Confederate forces. In June of 1863, she was asked to put this information to use and lead a raid by Union gunboats into Confederate territory.

Three gunboats — USS Sentinel, USS Harriet A. Weed and USS John Adams — left port on June 1 with 300 African American soldiers from the 2nd South Carolina Volunteer Infantry and the 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery. After the Sentinel ran aground, the two remaining gunboats, guided by Tubman, steamed up the Combahee River. Tubman guided them past treacherous mines and to specific areas on the river where enslaved people who had escaped from local plantations had congregated.

After landing a small detachment at the mouth of the river to deal with Confederate pickets, the Harriet A. Weed anchored a few miles upriver. The John Adams continued to Combahee Ferry, where it encountered a band of Confederate cavalry crossing a pontoon bridge. Shots from the gunboat scattered the troopers, and a party sent from the ship set fire to the bridge. These troops then went ashore, with orders to confiscate or destroy all viable property there. The John Adams, forced to stop by obstructions in the river, then moored at the causeway.

Confederate response to the invasion was slow, occurring as it did during the height of the malaria season, when only small detachments of troops remained along the rivers and swamps. Eventually, a battery of artillery arrived at the causeway and fired at the Union troops, but were quickly repelled by the big guns of the John Adams. By this time, the damage had been done, and plantations, mills and outbuildings were in flames. Union troops were able to confiscate stores of rice, cotton, vegetables and livestock. Most importantly, more than 700 enslaved people had flocked to the gunboats and were taken to freedom. The raid was a resounding success, thanks to the intelligence and leadership provided by Harriet Tubman, the only woman known to have led a military raid during the Civil War.

Colleen Cheslak, Communications Associate:

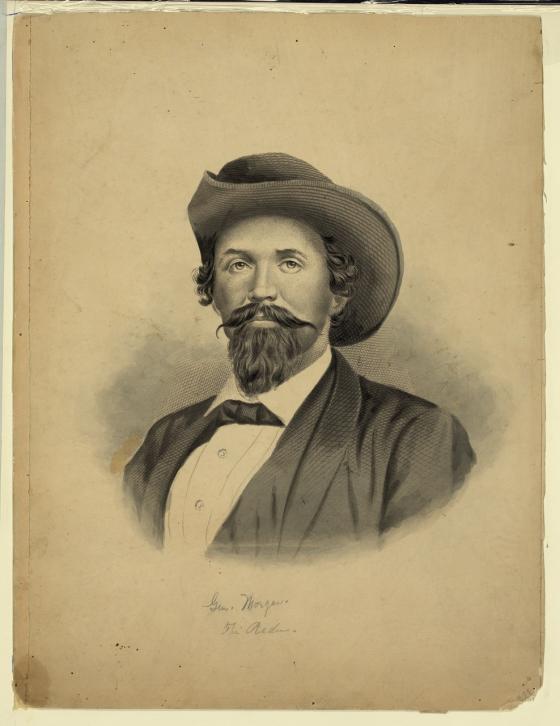

When the approximately five-year-old John Hunt Morgan moved to my native Kentucky between 1830 and 1831, little did he know the havoc that he would bring upon the Bluegrass State in the 1860s. Perhaps his 1844 expulsion from Transylvania College was a red flag — the consequence he faced for dueling with a fraternity brother. At minimum, it was an indicator of the fighting spirit he would come to embrace as a Confederate cavalry leader in the Civil War.

In an escapade that would lead Harper’s Weekly to label Morgan a “guerrilla, and bandit,” he and 900 Confederate cavaliers — “attached” to Gen. Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee — spent three weeks riding through Kentucky in the summer of 1862. This ride was all but calm, as Morgan and his “band of dare-devil vagabonds” disrupted the progress of Union forces by destroying railroad and telegraph lines, seizing hordes of Federal supplies, capturing a reported 1,200 Union soldiers, procuring hundreds of horses and — broadly speaking — unleashing hell upon his home state. Harper’s Weekly would also recognize Morgan as having “the most desperate courage,” as his path of devastation also paved a glimmer of hope for those who sought a fully Confederate Kentucky.

After the Confederacy’s dual losses at Vicksburg and Gettysburg in the summer of 1863, Morgan aspired to uplift the downtrodden by embarking on his most ambitious raid of the war. And he did so by ignoring the explicit orders of Bragg. Beginning in Tennessee, he expanded his cavalry’s hoofprints and crossed the Ohio River with approximately 2,400 men before riding more than one thousand miles along its north bank. For three weeks, Morgan’s Raiders terrorized the local defenses of southern Indiana and Ohio. His brazen tactics included having his telegraph operator act as a Union soldier, sending blatant misinformation regarding his actions, objectives and troop strength. But Morgan’s luck began to run out at the Battle of Buffington Island on July 19, 1863 — a massive blow that resulted in 750 Confederate cavaliers taken prisoner. Seven days later at the Battle of Salineville, defeat would amount to Morgan and a slew of his officers being sent to the Ohio State Penitentiary, while other cavaliers were sent to Chicago’s Camp Douglas.

Throughout their escapades, Morgan’s Raiders captured and paroled approximately 6,000 Union soldiers, ravaged 34 bridges, cut off rail lines at 60 sites and sidetracked tens of thousands of troops. Simply looking at Ohio, 2,500 horses were taken and more than 4,300 homes and businesses were raided. As a result, nearly 4,400 Ohioans filed claims for compensation with the federal government. However much damage the raids produced, they caused the number of Confederate veteran cavalrymen to dwindle while doing no significant harm to the transportation and communication infrastructure of the Union. Not to mention, they often inspired the Union to fight with an even greater degree of determination!

Garry Adelman, Chief Historian:

Ordered by Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee to take charge of and make observations of Union positions from a silk balloon just arrived in Richmond, Lt. Col. Edward P. Alexander was uneasy. His fear of heights was of a peculiar sort; ever since he had fallen off a cliff at West Point, he felt a strong urge to jump off any height he ascended. Just before his first balloon ascent outside Richmond in June 1862, he was calmed by an experienced aeronaut who said that the balloon experience was different: “You’re afraid of that feeling people have on steeples & precipices, but you needn’t be.” He was right. “The balloon had not risen 50 feet before I felt as safe & as much at home as if I had lived in one for years,” Alexander recalled of how he took to the balloon immediately. He also found that having a trained staff officer 1,000 feet up could be of immense military value, swiftly identifying Union reinforcements moving toward the Battle of Gaines’ Mill.

The Union army already knew this, of course. The previous year, scientist Thaddeus Lowe had demonstrated to the Lincoln administration the benefit of tethered balloons and soon became the Union army’s chief aeronaut. As with most things technological, the Union held advantages over the Confederates. Lowe’s balloons held more people, could launch from more places and consistently rose to higher altitudes for longer durations. Problems persisted nonetheless, leading, in one instance, to Union Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter’s harrowing and unintended journey over Confederate lines in an untethered balloon!

In May 1863, Lowe and his team supported General Hooker’s Chancellorsville campaign with frequent messages that could inform Union movements. Portions of two of Lowe’s messages to Hooker’s Chief of Staff Daniel Butterfield at 1:30 p.m. and 8:30 p.m. highlight the intelligence gathered:

- 1:30pm: The enemy opposite this ford occupy three positions from a half to one mile from the river, also opposite what I take to be United States Ford. About five miles up there is a small force. To the left of Banks’ ford, commanding the road, the enemy have a battery in position.

- 8:30pm: I … ascended at 7 o’clock, remaining up until after dark in order to see the location of the enemy's camp-fires. I find them most numerous in a ravine about one mile beyond the heights opposite General Sedgwick's forces, extending from opposite the lower crossing to a little above the upper crossing. There are also many additional fires in the rear of Fredericksburg. From appearances I should judge that full three-fourths of the enemy’s force is immediately back and below Fredericksburg.

Both sides launched from the ground and both used naval vessels for transport and launch as early “aircraft carriers.” Both also employed methods (telegraphs and signals) to relay actionable intelligence from the balloon to those on the ground. And while balloons were seen chiefly in the east, Union forces in the Western Theater used them to better direct their fire against Confederate positions near Island Number 10 in Missouri.

By the summer of 1863, both sides had effectively ceased aerial operations, favoring more traditional methods such as hills, platforms in trees and towers built for observation. For the South, which never fully enjoyed the fruits of aeronautical Special Forces, the cessation of balloon operations is not surprising. For the North, the disbanding of the Balloon Corps was puzzling on its face, and E.P. Alexander agreed, recalling, “[T]his would imply they did not finally consider [balloons] of much value. If so, I think their conclusion a decided mistake.”