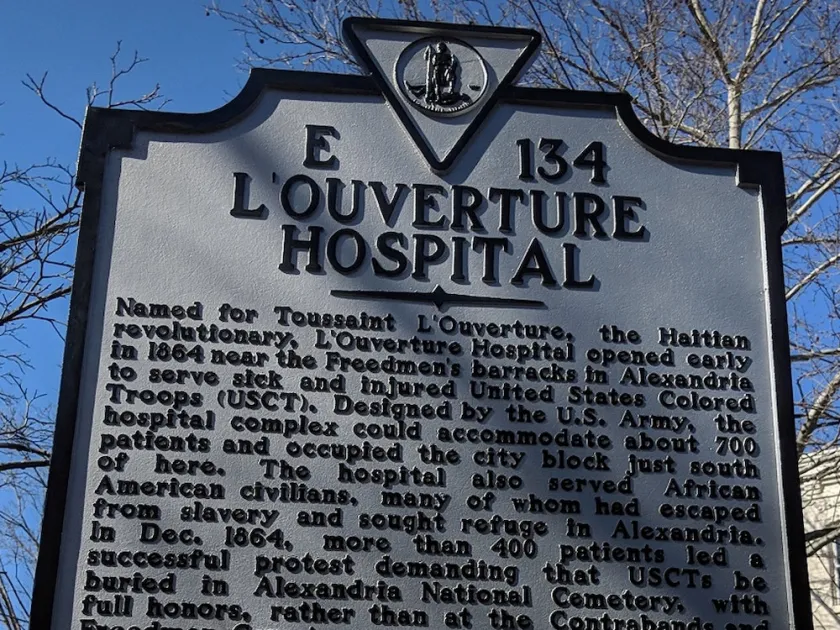

L'Ouverture Hospital And Barracks

Virginia

S Payne St

Alexandria, VA 22314

United States

This heritage site is a part of the American Battlefield Trust's Road to Freedom Tour Guide app, which showcases sites integral to the Black experience during the Civil War era. Download the FREE app now.

The U.S. Army opened L’Ouverture Hospital near this site during the Civil War to treat sick and wounded United States Colored Troops (USCTs). While patients at L’Ouverture, Black soldiers fought for equal treatment and for proper recognition of their service.

Alexandria was a logistical center for Union forces during the war. The army operated roughly 30 temporary hospitals in the city to provide care for thousands of sick and wounded soldiers. Named in honor of the prominent Haitian revolutionary leader and general Toussaint L’Ouverture (c. 1743-1803), L’Ouverture opened in early 1864 to serve USCTs. Black civilians - many of whom had escaped from slavery - also received treatment here.

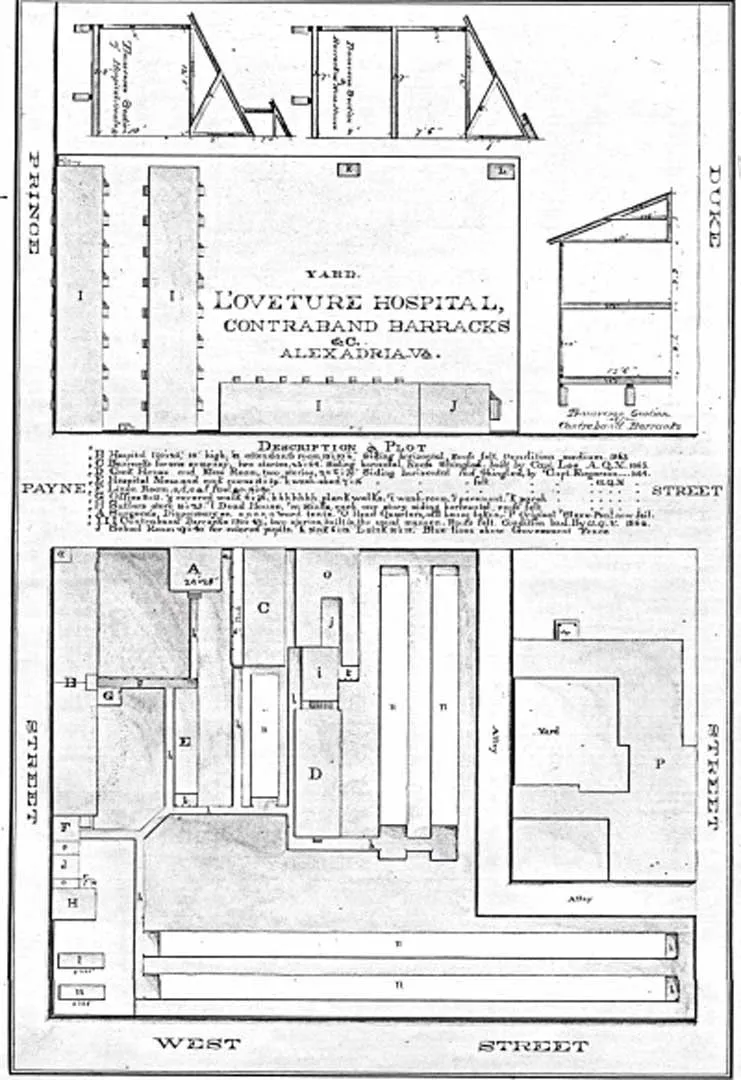

Encompassing most of this block, L'Ouverture could accommodate about 600 patients at a time. As you may see on the 1865 Quartermaster’s map (near the top of this page), structures once included barracks, a mess room, a linen room, an office, a sutler’s store, a dead house, a dispensary, and a school room. The only building that still stands today is a residence on S. Payne Street that served as an administrative headquarters.

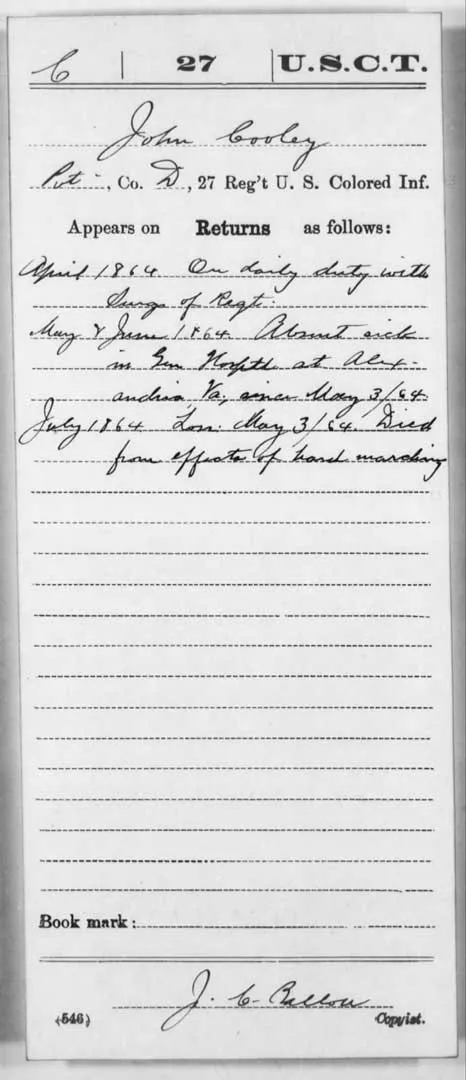

Scroll through the photos below to read more about some of the soldiers who received care at L’Ouverture:

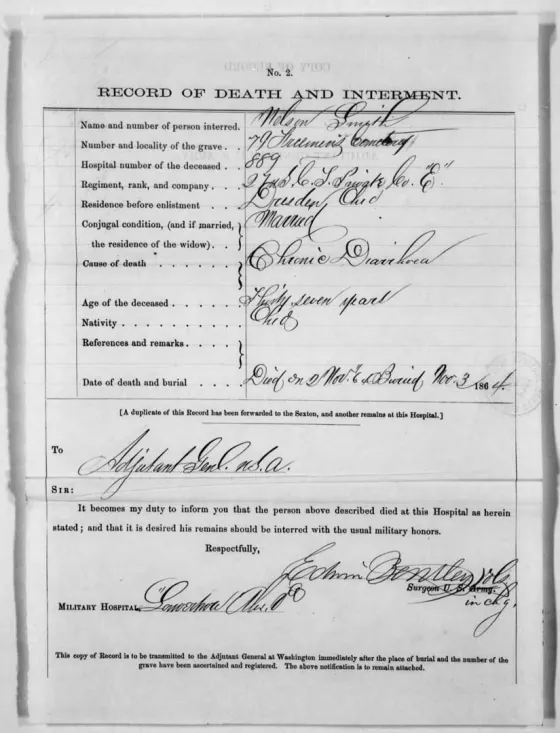

Black soldiers challenged discriminatory burial practices at L’Ouverture. Initially, many soldiers who died at the hospital were first interred with civilians in the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery on South Washington Street rather than in the Soldiers’ Cemetery (now Alexandria National Cemetery).

This would change. On December 26, 1864, Superintendent of Contrabands Rev. Albert Gladwin prevented a hearse carrying Pvt. Shadrick Murphy from going to the military cemetery. Outraged, over 400 patients supported a petition demanding Black soldiers be laid to rest in the Soldiers’ Cemetery with full honors, stating:

“…. As American citizens, we have a right to fight for the protection of her flag, that right is granted, and we are now sharing equally the dangers and hardships in this mighty contest, and should shair [sic] the same privileges and rights of burial in every way with our fellow soldiers, who only differ from us in color…” (National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 92; read the full transcription here)

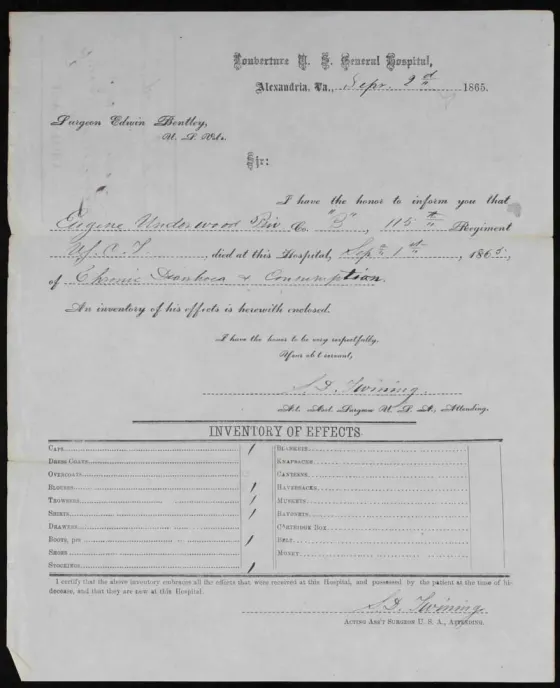

Patients first presented their demands to the hospital’s head surgeon, Maj. Edwin Bentley. Eventually the petition reached the quartermaster general of the U.S. Army, Maj. Gen. Montgomery Meigs, who agreed with the men of L’Ouverture. From then on, Black soldiers who died at the hospital were buried in the Soldiers’ Cemetery. Many of the soldiers who had been buried at the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery were disinterred and reburied.

The Black soldiers who received treatment L’Ouverture fought for equality both on and off the battlefield. Though little physical evidence of the hospital remains, their stand against injustice here left a lasting mark. Their actions ensured that – to this day – their fellow soldiers have resting places that are testaments to the sacrifices they made for the nation. Follow the links to learn more about Alexandria National Cemetery, as well as the Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery Memorial.