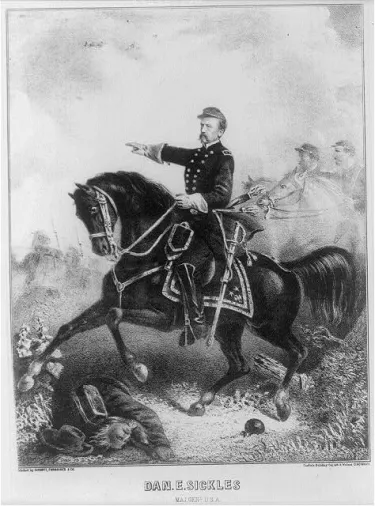

General Daniel E. Sickles has become known to generations of Gettysburg enthusiasts as the “amateur” general who disobeyed General George Meade’s orders at Gettysburg and advanced to the Peach Orchard instead of occupying Little Round Top. The debate over the merit of his actions has created some of Gettysburg’s most enduring controversies, and although beyond the scope of this article, these controversies have given Sickles an almost universally negative image among Civil War enthusiasts.

What has gotten lost amidst the negative Sickles portrayals is the often commendable work that he did in preserving the Gettysburg battlefield. Dan Sickles was a driving force in the early preservation and development of Gettysburg National Military Park. In addition to establishing the appropriate legislation in Congress, he was the leader in marking New York’s positions and monuments on the battlefield. Few veterans contributed as much to memorializing the battlefield as he did. Many men played significant roles on the battlefield, and many were significant in developing the National Military Park as we know it today. But Sickles is unique in having made significant contributions both during and after the battle.

Sickles spent most of the 1870s abroad, and like many of his contemporaries, initially had little involvement in veterans’ and battlefield affairs. He was Minister to Spain from 1869 to 1873. While in Madrid, he allegedly had an affair with Queen Isabella II, began a stormy second marriage to one of Isabella’s twenty-something attendants, quarreled with Secretary of State Hamilton Fish, was accused of using “child virgins for the purpose of prostitution,” and encouraged a war with Spain. Life with Sickles was never dull. He resigned and moved to Paris in 1874, before deciding to return to the United States in late 1879.

Meanwhile, the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association (GBMA) had preserved key battlefield locations in the years immediately following the battle, but during the 1870s the GBMA often lacked the necessary funds to continue aggressive preservation efforts. In 1878 the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) initiated efforts to take control of the GBMA. As a result of the GAR’s involvement, the 1880s witnessed an acceleration of Union veterans placing monuments on the battlefield.

Upon returning to New York, Sickles reportedly became moved by seeing impoverished veterans begging for money. Whether he then realized it or not, he had found a cause that would dominate the remainder of his life. He became more active in veterans’ affairs and when the veterans began to increasingly return to Gettysburg in the 1880s, Dan Sickles was among them. His initial return visits were in an unofficial capacity. As a colorful speaker and story-teller, he typically gave speeches and interviews that attempted to perpetuate a version of the battle where George Meade had wanted to retreat from Gettysburg and Sickles’ move to the Peach Orchard won the battle for the Union army.

The year 1886 changed the nature and intensity of Dan Sickles’ involvement with the Gettysburg battlefield. The New York State Legislature established the New York Monuments Commission for the Battlefield of Gettysburg, and Sickles was appointed the chairman. While preservation efforts today focus on restoring the field back to its war-time appearance, in Sickles’ era preservation often meant memorializing the battlefield with monuments. Sickles’ role was to oversee the placement of monuments to all New York regiments and batteries on the battlefield. The commission’s responsibilities also included securing appropriations, charting a battlefield map, and overseeing the creation of a detailed history of the battle (which, when published, was very flattering to Sickles’ battlefield performance). In addition to his activities with the commission, Sickles was also elected to the GBMA’s Board in June 1891 and served through that organization’s conclusion. He was also re-elected to Congress in November 1892, more than thirty years after he had left office in disgrace following his 1859 murder of Philip Barton Key. The New York Times would later marvel that Sickles was returning at “an age when most men are ready to retire.”

Despite the best efforts of organizations such as the GAR, GBMA, and Sickles’ own New York commission, large portions of the Gettysburg battlefield were threatened by commercial development through the 1890s. Most notably, local entrepreneur William “Boss” Tipton incorporated the Gettysburg Electric Railway Company in 1892, a venture which ran electric trolley tracks all over the field, including what had been much of Sickles’ advanced battle line. Tipton’s workers began heavy blasting and digging near Devil’s Den which threatened to desecrate what had been Sickles’ left flank on July 2, 1863. Public and veteran outcry was loud. Sickles complained of Tipton’s “blasting and leveling rocks and cutting the trees through the Devil’s Den region, robbing it of its mystery and jungle wildness. These made the place interesting . . . and gave a peculiar character to the battle which was fought at and from this point.”

With Tipton’s commercialization as the backdrop, the battle’s thirtieth anniversary in 1893 probably represented the high water mark of Sickles’ involvement in erecting monuments at Gettysburg. The first three days of July were designated “New York Day,” and Sickles was busy issuing directives throughout the spring. Rumors were circulating that veteran anger would be directed at Tipton’s enterprise. Chairman Sickles (a man who had once committed murder and advanced without orders on this very battlefield) issued an appeal to his men to “abstain from any act of violence against property of any description during their visit to Gettysburg, and to refrain from anything like discourtesy toward the persons identified with that undertaking, however obnoxious such persons may have made themselves.”

The highlight of “New York Day” was the dedication of New York’s National Cemetery monument on July 2. Sickles had long championed this monument, drawing the criticism of John Bachelder who was likewise a prominent figure in the battlefield’s early preservation. Bachelder complained that New York’s proposal to put a monument on the “summit” of Cemetery Hill would “overshadow everything on the field.” The monument as finally dedicated was not nearly as dominant as Bachelder had feared; comparatively few visitors today probably even see it, but Sickles did manage to incorporate his own wounding as one of four key battle scenes engraved around the monument’s base.

As “President of the Day,” Sickles gave the address. In addition to incorporating many of his favorite public-speaking themes, such as attacking General Meade’s Gettysburg performance, Sickles called on the government to stop the commercial destruction of the field:

The time has come when this battlefield should belong to the government of the United States. [Applause] It should be made a national park, and placed in charge of the War Department. Its topographical features not yet destroyed by the vandals . . . The monuments erected here must be always guarded and preserved, and an act of Congress for this purpose, which I shall make it my personal duty to frame and advocate [Applause] . . .

Despite Sickles’ prior warnings to “abstain” from violence against William Tipton, “some trouble occurred” on July 3 when Tipton attempted to photograph the veterans who had assembled on Little Round Top following the dedication of the 44th New York monument. Tipton was reportedly told to remove his camera, but declining to do so, Sickles and Dan Butterfield were accused of ordering the veterans to take it down. The Gettysburg Compiler claimed that “sharp remarks” were exchanged and that Tipton’s camera was “pushed down by some one of the veterans and said to be damaged slightly.” Tipton’s attorneys, who included David Wills, filed a claim of $10,000 against Sickles. Sickles was untroubled by the episode, after all he had been through much worse before, and told a reporter, “I think I have a right to determine whom I shall permit to photograph me.”

In Washington, Sickles actively championed battlefield and veteran affairs in the 53rd Congress, but the government had so far been unable to stop Tipton from blasting Devil’s Den apart in the name of the trolley tracks. On May 31, 1894, Sickles requested unanimous consent for the consideration of a joint resolution authorizing the Secretary of War “to acquire by purchase (or by condemnation) . . . such lands, or interests in lands, upon or in the vicinity of said battlefield . . . ” As the debate ensued in the House over whether the government truly had the right to acquire land, Sickles refused to water down the proposal, “if we can not have authority to condemn, then we are at the mercy of a lot of land jobbers, who want to speculate upon this historical ground . . . ” President Cleveland eventually signed the bill, and in 1896 the U.S. Supreme Court confirmed the federal government’s ability to protect historic land through condemnation. It was a landmark ruling for preservation, but the victory was primarily symbolic because Tipton had already done much of his damage and it would not be until 1917, several years after Sickles’ death, that the government finally appropriated $30,000 to purchase the land and dismantle the line.

Of more immediate and long-lasting impact was Sickles’ direct role in establishing Gettysburg National Military Park. Despite the great attention paid to it, Gettysburg was not the first Civil War battlefield to be designated a National Military Park. Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park was the first, having been created in August 1890. In passing the legislation, Congress recognized “the preservation for national study of the lines of decisive battles . . . as a matter of national importance.”

As early as 1890, Sickles had been championing the establishment of “a permanent military post, garrisoned by artillery” at Gettysburg. Over the years, he added a Soldiers’ Home, “perhaps also a GAR museum,” and the marking of the lines of both armies (he commendably supported marking Confederate troop positions when many other Union veterans did not) into a “proposed superstructure.” But nothing had been successfully accomplished during Sickles’ term in Congress, and before he could attend to any Gettysburg legislation, Sickles lost his re-election bid for the 54th Congress in late 1894. (Sickles actually did well in the election, but another Democrat faction ran a different candidate who predictably combined with Sickles to split the Democrat vote and they lost to their Republican opponent.) The Gettysburg historiography sometimes tells us (inaccurately) that Sickles had gone to Congress for the sole purpose of protecting Gettysburg with a National Park. If that were true, he certainly waited until the last possible moment to do so. He introduced what became known as the “Sickles Bill” when he reported as an outgoing “lame duck” for the 53rd Congress’ final session in December 1894.

Having already established the precedent at Chickamauga, there was little drama over whether the bill would pass, and the debate primarily concerned the details. Sickles’ proposal authorized the Secretary of War to purchase about 800 acres from the GBMA to be designated (along with the accompanying avenues and National Cemetery) as “Gettysburg National Military Park.” The park’s commissioners were appointed to superintend the opening of new roads, improve existing ones, and to “to ascertain and definitely mark the lines of battle of all troops engaged in the battle . . .” The Secretary of War was authorized to acquire lands “by purchase, or by condemnation proceedings.” Another section of the bill also authorized the secretary to erect “a suitable bronze tablet” containing Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address and “a medallion likeness of President Lincoln . . .” Sickles also added a provision to establish his long-planned branch of the “National Homes for Disabled Soldiers.”

As the proposal worked its way through the House, his Soldiers’ Home was dropped, but the proposed park boundaries were modified to not exceed “in area the parcels shown on the map prepared by Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles . . .” In other words, the initial boundaries of Gettysburg National Military Park were accepted based on a map that Dan had drawn up. What would become known as the “Sickles Map” remained in effect until 1974. So not only did Sickles push through the legislation, but for nearly the park’s first eighty years he determined its boundaries.

Although Gettysburg’s population was unsure as to what this all meant for their future, a debate that has not completely abated today, public response to the “Sickles Bill” was generally positive, particularly among veterans. The resolution passed through the House and Senate, and on February 11, 1895, the president officially signed the bill establishing Gettysburg National Military Park. It was the most lasting initiative of Sickles’ long career, even if the vast majority of Gettysburg’s modern visitors are completely unaware of his involvement, and many of his modern critics downplay his contributions. Sickles’ historical critics often state that surely someone else would have eventually established Gettysburg National Military Park if Sickles had not done so. But no one else had successfully done so during the four intervening years since the designation at Chickamauga and it is a matter of history that Sickles did get the job done. It serves as proof that no other player in the Gettysburg story has the combined battlefield and post-war influence as Dan Sickles.

With Gettysburg’s future attended to, Sickles remained busy in “retirement,” specifically continuing to chair the New York Monuments Commission. Unfortunately, despite Sickles’ considerable organizational and political abilities, he was also his own worst enemy. In late 1912, the state controller did an audit of the commission’s books and found approximately $28,486 missing.

Sickles was now in his early nineties, in failing health (reports of his being a ladies man until the very end were probably false), personally bankrupt (he had squandered a large inheritance from his father), and embroiled in a messy public squabble between his estranged second wife and his mysterious housekeeper, Eleanor Earle Wilmerding. It was readily apparent that he was no longer capable of managing his own household affairs, let alone the finances of such a large organization. One member of the commission stated, “It is most unlikely that the shortage was incurred with dishonorable motives or that there will be any criminal prosecution. General Sickles allowed the shortage to occur through laxness rather than design.”

Although many veterans, his estranged second wife and son, and James Longstreet’s widow were among those who came to his assistance, Commissioner Sickles was facing potential jail time. But fifty years worth of battlefield speeches paid off for him. He was a celebrity and bona fide war hero. New York was facing a public relations nightmare. Sickles’ attorney (whom Dan’s son believed was partially responsible for the missing money) arranged for Sickles to remain free on bond and he avoided jail time. But New York never received the money, and it was an embarrassing end to several decades’ worth of Sickles’ positive preservation work. Not surprisingly, today it historically overshadows all of his better efforts.

Sickles’ Gettysburg adventure ended with the battle’s 50th anniversary in July 1913. Sickles returned to the battlefield that he had helped preserve, and he knew it would be for the last time. “We don’t say it, but ‘my boys’ know, and I know, that we shall probably never meet again.” He was the center of attention, and although he took one last opportunity to take a few swipes at George Meade, he generally took the high road, telling newspapers, “I believe I am living right now the happiest days of my life.”

Sickles had been accompanied by his old Excelsior chaplain Joe Twichell. As Sickles and Twichell looked out over the field together one final time, Twichell is said to have expressed surprise that there was still no Sickles statue on the field. A monument to his old Excelsior brigade had been dedicated in 1893 with the understanding at that time that a Sickles statue would be added to it after his death. As late as 1907, Sickles had still hoped for a monument on the battlefield, writing, “if at some future time it may be the pleasure of the State of New York to place some memorial of myself on that battlefield I should prefer to have it on the high ground at or near the Peach Orchard . . .” Battlefield legend tells us that Sickles allegedly replied to Twichell (to the effect) that the whole damned battlefield was his monument.

While we may never see a Sickles statue on the field, the results of his efforts to protect and mark the battlefield are, in fact, nearly everywhere. The park’s lengthy “Sickles Avenue” runs over most of the Third Corps line. The Excelsior Brigade monument, even without the legendary missing bust, commemorates both he and the men he raised in New York. A marker near the Trostle farm denotes where he was wounded, while the New York Monument in the National Cemetery dramatically depicts the moment. The back-side of the Lincoln Speech Memorial credits Sickles with introducing the legislation that established the park and erected the monument. His name sits at the top of the New York Auxiliary State Monument, dedicated in 1925 (after his death) to the memory of all New York commanders who were not individually honored elsewhere. Under his leadership, New York placed eighty-eight monuments on the battlefield, the state monument in the National Cemetery, and statues to two generals (Slocum and Greene). Locales such as Devil’s Den, the Wheatfield, and the Peach Orchard might not have any significance today, and perhaps might not have been preserved, were it not for his July 2 advance. He established the Park’s initial boundaries. Even the fence separating the National Cemetery and the local Evergreen Cemetery was the same that stood in Lafayette Square when Dan killed Philip Barton Key in 1859. The whole damn battlefield might not be his monument, but he certainly has his share of it. Whatever one may think of his personal character, or of his battlefield actions, anyone who enjoys the Gettysburg National Military Park today owes a debt of gratitude to Dan Sickles.

Related Battles

23,049

28,063