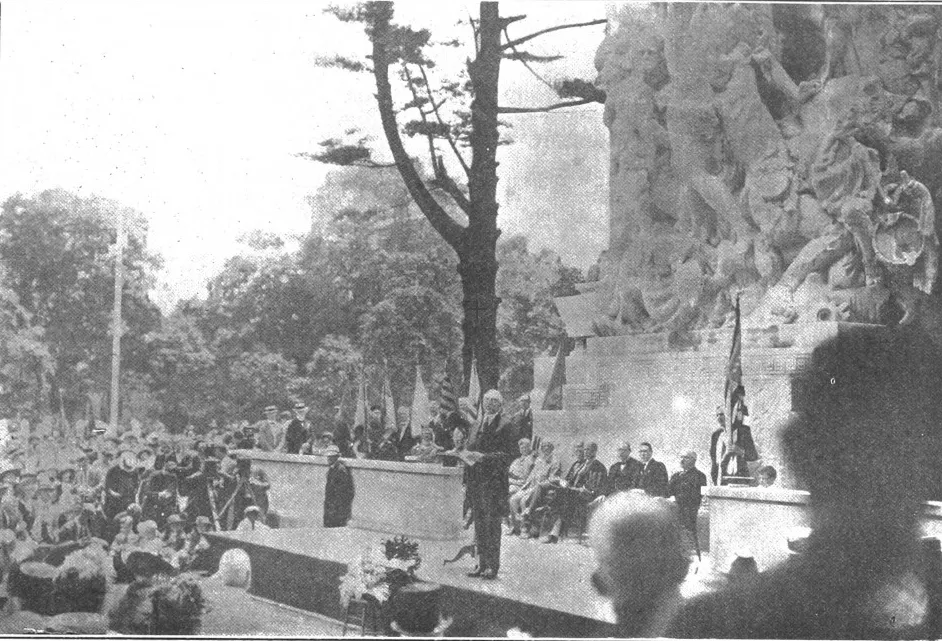

Dedication Speech Delivered by Warren G. Harding for the the Princeton Battle Monument

The Dedication speech for the Princeton Battle Monument was delivered by President Warren G. Harding’s on June 9, 1922, in honor of the Battle of Princeton fought on January 3, 1777.

My Fellow Americans:

We have come here to say the formal words of dedication and consecration before a monument in stone. But we stand, to say those words, in the presence of another monument, which is the true memorial to the events we celebrate. The real monument to the achievement of Washington's patriot army in the Trenton-Princeton campaign, is not to be sought in the work of hands or in memorials of stone. It rears itself in the institutions of liberty and representative government, now big in the vision of all mankind.

In the presence of such a monument, we can do no better than consecrate ourselves to the cause in which at this place the soul of genius and the spirit of sacrifice shone forth with steadfast radiance. On no other battle-ground, in presence of no other memorial of heroism, could" we find more assuring illumination for our hopes, our anticipations, our confidence. Here the genius of General Washington reached the height of its brilliancy in action. Here his followers wrote their highest testimony of valor. Here liberty-seeking devotion struggled through privation and unbelievable exertion, to gain the heights. The crimsoned prints of numbed and bleeding feet marked the route a pathway to eternal glory. Thither they trudged through storm and torrent; but from here, in the hour of victory, went out winged messengers to let all men know that liberty was safe in the keeping of her sons.

Point me the field of strife, to which have converged more roads that led through discouragement, calamity, and all justification for despair! And point me, next, that field from whence radiated so many highways of the buoyant heart, the confident hope, the indomitable purpose, the will to win! Take down the tomes, thumb all the blackest, all the fairest pages, and tell me where you read of nobler, finer, — aye, or more fruitful — sacrifices of men for their fellows!

Here, among you to whom the traditions of those events are a sacred trust, is no place for recounting the discouragement of the patriot cause, the low ebb of Continental fortunes, the seeming that final disaster could not long be stayed. Almost from the day, in the preceding summer, when the great Declaration had been issued, misfortune had followed on mis- fortune's heel — Long Island, the loss of New York, the surrender of the Hudson forts, the retreat across New Jersey, the refuge in Pennsylvania. It was all leading toward the seemingly inevitable end. The army was crumbling, only civil authority pretended to maintain any central organ. The enemy delayed to finish his task, only because he was so certain of his quarry that haste would be unseemly.

And then, the flash of Washington's defiance! The crossing of the Delaware in storm and ice floes; the march, and the delays which made it impossible to effect a night attack and a complete surprise; Washington's stern and fateful decision to press on and stake everything on the issue; finally, the attack, and the victory.

Brilliant as was the accomplishment, Washington, on the Jersey side, was faced presently by the superior strength of the new consolidated British forces. At last his rival was sure of "the old fox." Then came the strategic withdrawal by Washington at night, in secret, from his line on the Assunpink Creek, the flanking march to Princeton, and the second surprise and defeat of the enemy. In the narrative of those magnificent winter days of marching and fighting, surprises and victories, one finds the truest presentation of the indomitable spirit which sustained, and, at last, won the Revolution.

It is not often that the precise importance and significance of a particular military detail can be so accurately appraised, as it can regarding the midwinter campaign of Trenton-Princeton. The promulgation of the Declaration of Independence had moved the British authorities to especially determined efforts for quick suppression of the revolution. To them it was vitally important that the fires of revolt be smothered before the new feeling of nationality had risen to make the Colonists realize the substantial unity of their cause and their interests. The strategy of the British invasion of New Jersey has been bitterly criticised many times, but it must always be remembered that there is an intimate relationship between political conditions and military operations, and that in this case the political situation was certain to depend very greatly on military developments. The destruction of Washington's army would almost have snuffed out the revolution. It would have given a demonstration of the overwhelming preponderance of British power, which even the most stout-hearted patriot would have found difficult to deny. On the other hand, Washington perceived both the military and the political opportunity presented to him in the disposition of the enemy's forces. There was a desperate chance to win a telling victory which would convert the New Jersey campaign into a disaster for the enemy; and there was also the possibility of winning a political victory by demonstrating the capacity of American leadership and American soldiers to outwit and outfight veterans of European battlefields.

Washington, who was at once soldier, politician and statesman, recognized all these possibilities. He seized the opportunity, he turned it completely to his own advantage, and thereby inspired his army and the country behind him with a new confidence in themselves. Years afterward, Lord Cornwallis, and the members of his staff, were given a dinner by General Washing- ton, following the surrender at Yorktown. The compliments of the occasion were exchanged in a manner so gracious and amiable that, as we read of it now, it is difficult to realize all their significance. Among the rest. Lord Cornwallis made a speech in which he paid his compliments to the military genius of Washington. Comparing the Yorktown campaign with the Trenton-Princeton operation, he declared, turning to General Washington, and bowing profoundly, that, "When history shall have made up its verdict, the fairest laurels will be gathered for your Excellency, not from the shores of the Chesapeake, but from the banks of the Delaware." Cornwallis regarded the Trenton- Princeton campaign as the crowning glory of the Washington military career; and we do not need to be reminded of the verdict of Frederick the Great, who ranked the Trenton-Princeton campaign as the most brilliant of which he had knowledge.

When we view the course of human affairs from the detached standpoint of history's student, we are amazed to discover how seldom a particular military operation has determined the results of a campaign or the outcome of a great war. Wars are writ very big in history; very much bigger sometimes than they deserve to be. Battles have seldom decided the fates of peoples. The real story of human progress is written elsewhere than on the world's battlefields, and war and conflict have provided rather its punctuation than its theme. But among the exceptions, among the cases in which a particular conflict has had consequences and reverberations far greater in their potency than could possibly be imagined from a consideration of the numbers engaged or the immediate results, none stands out more distinctly than does the Trenton-Princeton campaign. We cannot say that the cause of independence and union would have been lost without it; but we must find ourselves at a loss if we attempt to picture the successful conclusion of the revolution, had there been another and different issue from the struggle of those hard, midwinter days.

The climax of that desperate adventure came on the field of Princeton. Trenton had been an almost complete surprise, an easy victory. Princeton was a desperately contested engagement whose immediate result included not only an enheartening of the patriot cause, but a profound discouragement to those on the other side of the Atlantic, who were responsible for the continuation of the war. So you have erected here at Princeton a fitting memorial to the heroes and heroism of that day. We bring and lay at its foot the laurel wreaths which gratitude and patriotic sentiment will always dedicate to those who have borne the heat and burden of the conflict. Let us believe that their example in all of the future may be, as thus far it has been, a glorious inspiration to our country.

Discarding his manuscript at the end of the address, President Harding stepped slightly forward and said :

Mr. Stockton, before I conclude I want to be just a bit informal. If I had found no other compensation in a trip to Princeton, it would have been in two things new to my experience.

Pointing to the various revolutionary flags that had been draped against the monument by Sons of the American Revolution, he went on:

One was the presentation of the colors, beautifully done, where I saw for the first time the combination of the colors that represented the hopes and aspirations and determinations of the early American patriots who gave us our independence and union, and then saw those colors blended into one supreme banner of Americanism — our dear Old Glory.

Turning to the guard of honor dressed in uniforms of a century ago, President Harding continued:

The other compensation, my countrymen, was in seeing the Philadelphia Troop and the infantrymen of the Fifth Maryland. It is not so much in the men themselves and the wonderful appearance they made today, but the compensation is in the thought that these organizations have been in continuous service since the days of the American Revolution.

They stand today and typify those who gave us independence and freedom. I think it is well, my countrymen, and I like this monument. I like every memorial to American patriotism and American sacrifices. No land can do too much to cherish with all its heart and soul these great inheritances.

Somehow there comes to my mind the assurances that in the preservation of these organizations of the Philadelphia Troop and the Fifth Maryland there is a tie running back to the immortal beginning of this American Republic, and we of today and the veterans of the World War, the sons and daughters of the men who go on, will keep these supreme inheritances and carry them on to a fulfillment of a great American destiny.

Click here for the full text of ceremonies.