Prior to the American Revolution, the issue of unjust taxation by the British was a common source of frustration that echoed throughout the colonies. The North Carolina Regulator War, also called the War of Regulation, was a series of insurrections and protests led by settlers who fought against the unfair taxation and injustices of the royal colonial officials between 1765 and 1771.

During the 1760s, there was an influx of immigration to North Carolina, primarily bringing people from Ireland and Scotland to the colony. At this time, North Carolina was somewhat divided between the wealthier and more settled east and the more rural, less settled west. The eastern region was the home of the provincial government and most of the royal officials. The western area of the colony, also called the backcountry, consisted mostly of poor farming settlers whose income and resources were dependent on the yield of their crops. The backcountry settlers mostly shared similar backgrounds and social levels. Things began to change as the population of the colony boomed from immigration, and a new and diverse wave of immigrants moved into the rural west, disrupting the stable social order that the farmers had maintained. Wealthy merchants from the eastern cities of North Carolina followed the new immigrants hoping to help settle the emerging west. While the influx of new settlers flocked the west, the farmer population was already struggling as a drought-plagued the area. Because of the drought, the farmers were unable to harvest food and maintain an income. The new settlers exacerbated the farmers’ already poor conditions further by transforming the social orders of the region.

Hope grew dim for the backcountry farmers and planters as the provincial government, located in the east, levied taxes that they could not pay. The wealthy North Carolina government officials were ignorant of the struggles of the lower class. The farmers who had once ruled the backcountry were now alienated among the other classes. These farmers, whose incomes were little and whose resources were none, were forced to turn to the newly arrived merchants for goods. The Currency Act of 1764 demanded that taxes and debts be paid in gold or silver coins, a currency that the farmers scarcely had. Therefore, when the farmers inevitably could not pay both their taxes and their new debts, the merchants, who had no ties to the rural population, were swift to take the indebted farmers to local courts which were controlled by the wealthy British.

The wealthy British officials in power were known to most of the lower-class North Carolinians as the “courthouse ring,” a group of corrupt officials who often preyed on the poor and unjustly extorted the colonists for their own gain. When farmers were brought to court, they were forced to pay in labor or through other unfair means. It was not uncommon for the courthouse ring to take the farmers house as collateral, force them to pay fake court dues or extort them for horses or farming equipment to pay off their debts. The officials would then often take the goods and sell them as their own, pocketing the profit for their own gain. Overall, the corrupt system of officials led to further class division and tension between already frustrated poorer citizens and the colonial government. In 1765, King George III appointed British General William Tryon as Provincial Governor of North Carolina. The provincial government under Governor Tryon reached an extreme level of corruption. Nearly every official in power extorted money from the lower-class colonists under the guise of taxation. These illegal activities went unchecked by Governor Tryon as he did not want to lose the support of the colony officials. The colonists were enraged at the injustices that they were experiencing.

The first call to action against these injustices was a speech given on June 6, 1765, by schoolteacher George Sims, a planter from the Nutbush township of North Carolina. The speech, referred to as the Nutbush Address, called on colonists to protest the unfair taxation and corruption of the colonial officials. This address prompted all colonists who sought justice to band together and form the group that came to be known as the Regulators. Their name, the “Regulators” was an embodiment of their goal to regulate the corrupt government and the unfair taxation levied against the settlers. The Regulators were not seeking to overthrow the government, but rather to destroy the corruption that dwelled within it. The series of colonist rebellions against the wealthy colonial elite and officials that followed would be known as the Regulator War or the Regulator Movement.

One of the leaders of the Regulators, Herman Husband, was a Quaker who did not believe in violence and instead chose to petition for change. At the urging of Husband, the first actions of the Regulators consisted of peaceful protests and petitions to the government to replace the corrupt officials with local colonists who knew the struggles of the lower classes. However, the provincial government was unmoved by the protests, and merely shut them down. Although the Regulators saw no sympathy from the government, the government inaction proved beneficial to them as it prompted more colonists to see the need for change and join the Regulator Movement. In the summer of 1768, the Regulators were finally able to meet with Governor Tryon who came to certain agreements with the protestors; however, he soon retracted all promises of change that he had made. By the Spring of 1769, the Regulators were not only protesting, but also refusing to pay the taxes unfairly levied against them.

In 1769, Governor Tryon dissolved the General Assembly and called for new elections. Herman Husband and another Regulator leader, John Pryor, were elected to the colonial representatives, a small victory for the movement. However, it quickly became apparent that the other government officials would not let them pass any legislation. In time, the General Assembly actually expelled Husband from the legislature, accusing him of promoting rioting. In the meantime, Governor Tryon also had an estate built, “Tryon’s Palace,” at the expense of the public. By 1770, these continued unjust actions by the colonial officials fanned the flames of Regulator unrest.

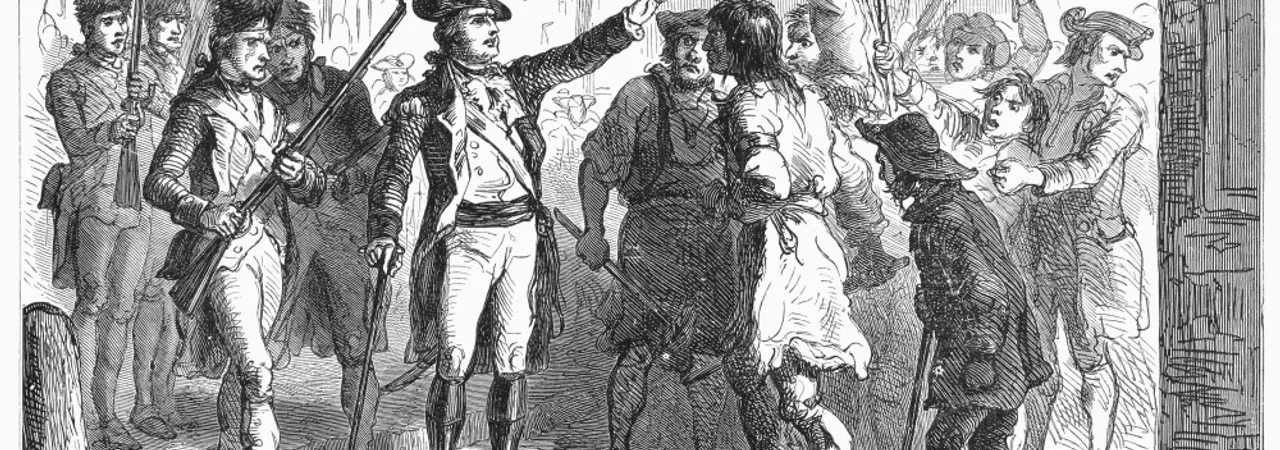

At this point, the angered colonists decided that it was time to stray from leader Herman Husband’s peaceful approach and use violence to convey their point. In September 1770, a group of Regulators marched into Hillsborough, a town in the eastern area of the colony, where the colonial court was in session. The mob stormed the court, vandalizing the courtroom, and dragging multiple officials through the streets, looting shops as they ran through the town. One of the men that the Regulators seized was Edmund Fanning, British lawyer and close friend of Governor Tryon, who frequently extorted the colonists and was seen by many as the face of the governmental corruption. They attacked Fanningm leaving him severely injured, and then marched to his house where they looted the house and barn, and then burned both down.

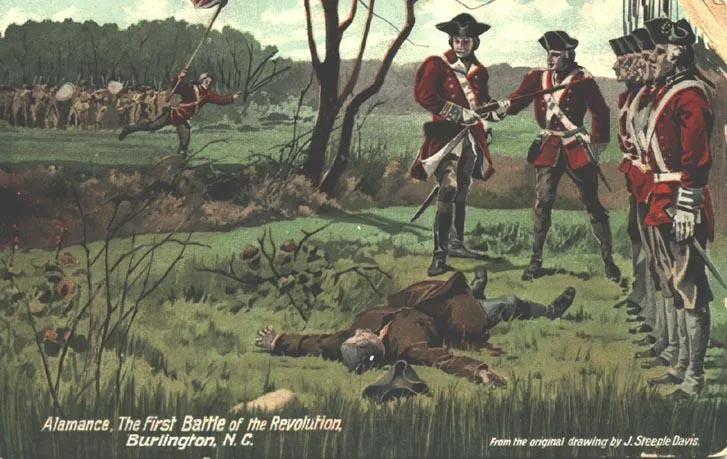

After the riot, Governor Tryon began building an army of trained militia to prepare to fight against the Regulators. In January 1771, in response to the Hillsborough riot, the general assembly passed the Johnston Riot Act which gave the government the right to prosecute rioters and to use force against them. Later that year, the Regulators tried once more to reason with Governor Tryon and call his attention to the abuses of power, however, the Governor refused to meet. The actions of the Regulators the previous year had convinced Governor Tryon to use his army to meet the rioters with force. In May, Tryon and his trained militia of over 1,000 armed men marched toward the camp of the Regulators on the Alamance Creek near Hillsborough, where the courthouse riot had occurred months earlier. Despite being unaware of the number of Regulators, Governor Tryon was confident that he had the military advantage, and he was correct. Although the Regulators outnumbered the militia by nearly 1,000 men, they were untrained with limited weapons and unstructured leadership.

On May 16, 1771, the Regulators faced Governor Tryon’s militia in the Battle of Alamance, the first and only real battle of the war. The Regulators made their final attempt to reason with Governor Tryon. To this, he responded that he would meet with them if they gave up their weapons and dispersed. The Regulators refused to disperse, prompting Tryon to read the Johnston Riot Act and warn them that he would fire on them if they did not comply. James Hunter, a leader of the Regulators, famously responded “Fire and be damned!” At noon, Tryon and his militia fired, and so began the Battle of Alamance. Some sources claim that Governor Tryon fired the first shot of the battle, killing a Regulator, although this claim is disputed. In total, the battle lasted about two hours before the colonial militia had defeated the Regulators.

The number of casualties among the Regulators is unknown, but 9 of the colonial militia died and 61 were wounded. When the battle ended, the number of prisoners taken by the militia varies among sources but remains between 12 and 15 Regulators that were taken, prisoner. Seven of the Regulators were executed, while the rest were pardoned by King George III at the suggestion of Governor Tryon. Over the next few weeks, Governor Tryon issued a pardon to any rebel who would sign an oath of loyalty to the government. The majority of the Regulators signed the oath, and those who would not comply went into hiding or exile. Some even joined other rebel groups in neighboring areas in Tennessee. Those who stayed in North Carolina were defeated, disbanded and forced to go back to the lives they lived before they took any action against the government. There are even reports that Governor Tryon once more raised taxes after the Battle of Alamance to pay for the cost of the militia who served there.

While some claim that the Regulator War was a catalyst to the American Revolution, the idea is highly disputed among historians. The American Revolution was a war fought for the independence of the colonies from the British, whereas the Regulators at the time stayed loyal to the British government and merely fought for governmental reform. When the American Revolution began, many Regulators even stayed loyal to the crown, while some of Governor Tryon’s militia, who fought against the Regulators at Alamance, joined the Patriot cause.