The Regulator War

In 1771, four years before the “shot heard round the world” rang out on Lexington Green, there was a battle in North Carolina between colonists, who had assembled to defend their liberties, and soldiers sent to disarm and disperse a serious challenge to colonial authority. At Alamance Creek, militia under the command of Governor William Tryon of North Carolina defeated a group of backcountry settlers calling themselves “Regulators,” and put an end to the short-lived rebellion in the Piedmont region of North Carolina that became known as the “Regulator War.”

Settlers flooded into the Piedmont region of North Carolina in the middle of the 18th century. War and disease drove the Native inhabitants out of the region, and farmers were drawn by the promise of cheap and abundant land. Small farmers believed that the Piedmont held the promise of economic independence, but there were major challenges to that dream. Speculators inflated the price of land, and corrupt officials often cheated or extorted small farmers. Once farmers were settled in the region, they found themselves in debt, often to multiple lenders. When loans came due and farmers couldn’t pay, they lost everything. The tax system of colonial North Carolina also fell unequally on poorer colonists, while wealthy landowners paid little in taxes. Making all this worse, many of these taxes and debts could only be paid in hard currency, which was in short supply. Officials in the region charged high fees for their services, often in violation of the law, and colonists who sought to challenge them in court faced expensive and usually futile lawsuits. The courts were controlled by the same local elites who held public office and profited from the corruption.

In 1766, residents in Orange County, North Carolina formed the Sandy Creek Association. The Association presented a manifesto to the court at Hillsborough, petitioning for reforms to the system that would address corruption and extortion. The petition had little effect, and the Association ceased to exist in late 1767, but this marked the beginning of political activism in the Piedmont that would eventually turn into armed resistance. In 1768, a new movement began to organize. In Orange County, but also in neighboring Anson, Rowan, and Mecklenburg Counties, colonists who sought to address the ongoing corruption began to form groups called Regulators. The word Regulator had first been used in England in 1655 to refer to someone who was appointed to address abuses of power. Herman Husband, one of the Regulator leaders, said that the Regulators sought “to be Governed by Law, and not by the Will of officers.”

The Regulators were not formed to oppose the colonial government. Rather, they wanted to use legal means to seek redress for their grievances. They sent petitions to the colonial assembly, they filed suit in the courts at Hillsborough, and they tried to get high-ranking colonial officials to meet with them to hear their complaints. But when these methods failed to bring any meaningful change, the Regulators began to use extralegal means to achieve their goals. Regulators pledged not to pay their taxes, they took back property that had been confiscated because of unpaid debts, and they disrupted the proceedings of courts. Governor William Tryon tried to call up the militia to suppress the Regulators, but the militias of the Piedmont counties refused to fight their neighbors. Governor Tryon agreed to hear their petition if they dispersed, which the Regulators did.

Like the Sons of Liberty, the Regulators initially believed that the colonial government would be sympathetic to their plight if they were made aware of the situation in the Piedmont. But Governor Tryon proved totally unsympathetic to the petitions of the Regulators, and in fact, took several steps that inflamed and escalated the situation. He told the Regulators that “the Grievances complained of by no means Warrant” their actions, which “tended to the subversion of the Constitution of this Government.” Meanwhile, many of the colonial elites who encouraged and led the protests against the Stamp Act, and who would play a role in the American Revolution, sided with the royal governor against the Regulators. They saw the Regulators not as allies against the British government, but as a threat to their position and privileges.

In 1769, the farmers of the region had succeeded in electing some of their allies to the colonial assembly, including Herman Husband. But the assembly did nothing to address their concerns. Instead, the focus of the assembly was on responding to the Townshend Acts. When members of the assembly began discussing a nonimportation agreement, like the one formed by colonists in Virginia, Governor Tryon dismissed the assembly. Frustrations boiled over on September 24, 1770. A large crowd of Regulators attacked several members of the local elite in Hillsborough, including a sheriff and several justices of the peace. Other officials fled the city, fearing for their safety. The crowd ransacked the home of Edmund Fanning, a particularly disliked official. In response, the colonial assembly passed the Johnson Riot Act, which applied harsh penalties to anyone who assembled “unlawfully, tumultuously and riotously” and did not disperse when ordered. Herman Husband was expelled from the assembly and arrested, though he was eventually released.

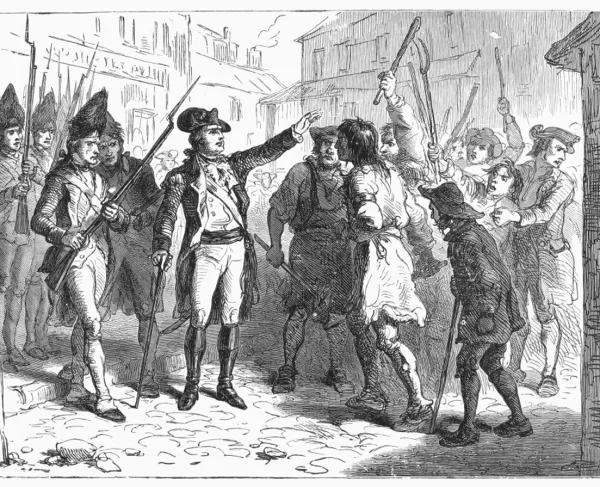

The Johnson Riot Act gave Governor Tryon the legal justification he needed to suppress the Regulators with military force. He entered the Piedmont in early May, with approximately 1,100 militiamen from the eastern counties of North Carolina, six swivel guns, and two brass cannons. Among the leadership of this army were a number of future Patriots; Tryon’s artillery was commanded by Robert Howe, who would later rise to the rank of major general in the Continental Army. Tryon and his force entered Hillsborough on May 11, 1771, and two days later marched to the west bank of Alamance Creek twenty miles west of the town, where between two and three thousand Regulators were camped. After several days of standoff, on May 16, Tryon advanced his army towards the Regulator camp. He delivered an ultimatum: he would not attack if the Regulators surrendered their arms and their leaders, and promised to obey the law. The Regulators rejected the ultimatum. Just before noon, Tryon gave the order for his cannons to open fire. The Regulators, firing from behind cover, were able to achieve some initial success against the militia. But their ammunition soon ran low, and Tryon’s militia set the woods that the Regulators were using as cover on fire. After two hours, the battle was over. Nine of Tryon’s militiamen and between 9 and 20 Regulators had been killed, while more than 150 men were wounded. Many Regulators were taken prisoner. The day after the battle, a captured Regulator named James Few was hanged on the battlefield without any trial.

Governor Tryon issued a proclamation, offering to pardon all Regulators who came to his camp, surrendered their weapons, and took an oath of allegiance promising to obey the law and pay taxes. Eventually around three-quarters of all free men in the Piedmont region would take the oath. Herman Husband fled the colony, with Governor Tryon offering 100 pounds and 1,000 acres of land to anyone who brought him in dead or alive. The army marched with its prisoners back to Hillsborough, where fourteen captured Regulators were put on trial. Twelve men were condemned to death. Tryon pardoned six of them, but on June 19, 1771, the other six men were executed outside Hillsborough. Governor Tryon left Hillsborough the next day, and on June 30 he left North Carolina to take up his new position as Governor of New York.

King George III eventually issued a pardon for all Regulators except for Herman Husband, who fled North Carolina and started a new life in western Pennsylvania. The suppression of the Regulators, which was led and championed by some of the same members of society who were organizing the resistance to British colonial rule, turned many people in the North Carolina backcountry against the Patriot cause. A few months after Lexington and Concord, an inhabitant of the Piedmont wrote that no revolutionary Committee of Safety had been formed in that area because “the last Regulator Rebellion, which cost many lives and brought many into poverty and need, has made people afraid of hurting themselves again, for the burned child dreads the fire.”

There was also a Regulator movement in South Carolina, though it had very different goals and allegiances. The South Carolina Regulators were a much smaller group, and they were wealthier men who owned property on the colony’s frontier. A dispute between the colonial assembly and Parliament delayed the establishment of courts, jails, and other government functions in these frontier communities in the late 1760s. Instead, the South Carolina regulators dispensed vigilante justice against bandits and criminals. Unlike the North Carolina movement, the South Carolina regulators achieved their goals. In 1769 colonial assembly passed laws that addressed the needs of the regulators, creating judicial districts with courts and jails on the frontier. In 1771, Governor Charles Montague issued a general pardon for all regulators.

The Regulator War in North Carolina served as a prelude to the Revolutionary War. While the Regulator War was a class-based revolt, similar to Bacon's Rebellion in Virginia, the Regulator War was only the beginning of the straining relationship between North Carolinian colonists and the British government. This strain boiled over just four years later, where North Carolina, along with twelve of her sister colonies, fought for their freedom from a tyrannical government.