Pontiac's Rebellion

Violence once again shattered the forests west of the Appalachian Mountains in the spring of 1763. The peace brought on by the end of the French and Indian War, which gave Great Britain control over much of the continent, disintegrated in what became known as Pontiac’s War or Pontiac’s Rebellion.

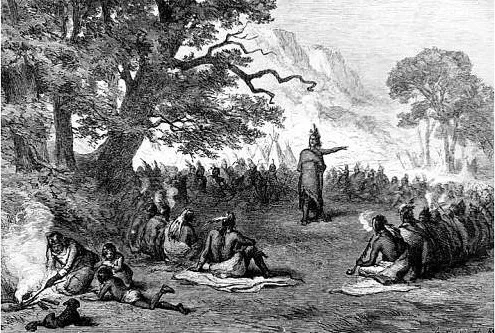

Influenced by the unwillingness of the British to establish alliances, the preaching of a Delaware holy man, Neolin, ignited the struggle between the various Native American tribes and the new power in North America. During a vision, Neolin conversed with the Master of Life, who emphasized to him the need to reject colonial society and return to the traditional native ways. Neolin’s words profoundly impacted an Ottawa war chief, Pontiac. The Ottawa inhabited the region around the Great Lakes and Pontiac worked to establish a Pan-Indian coalition with the nearby tribes.

Beginning in the second week of May, warriors struck the British forts in the Ohio Valley. Pontiac himself initiated a siege on Fort Detroit. At the end of July, in the hopes of breaking the warrior position, Capt. Henry Dalyell led elements of the 55th, 60th and 80th Regiments of Foot in a sortie against the warriors. Pontiac, however, ambushed Dalyell at Parent’s Creek, later renamed Bloody Run. Pontiac inflicted heavy casualties on the British, however, a stand by Maj. Robert Rogers and a contingent of his Rangers allowed the column to safely return to the fort.

A week after the siege of Detroit began warriors assailed Fort Sandusky followed by assaults on Fort Miami and Fort Saint-Joseph. On June 2, the tribes achieved a major victory with the capture of Fort Michilimackinac, located in the straits between Lake Huron and Lake Michigan. The attacks extended beyond the Alleghenies to western Pennsylvania as the warriors laid siege to Fort Pitt. Pontiac’s offensive, although largely uncoordinated, put the British Commander-in-Chief, Sir Jeffrey Amherst on his heels.

Despite these early victories, by late summer, the effort began to lose momentum. In early August, a party of Shawnee, Delaware, Mingo, Huron and Ottawa ambushed Col. Henry Bouquet, enroute to Fort Pitt near Bushy Run. Bouquet’s force, part of which consisted of the 42nd Regiment of Foot (Black Watch), put up a stubborn two-day fight and eventually broke through to relieve the garrison.

Unable to maintain his coalition, Pontiac decided to abandon the siege of Detroit in late October. The siege proved to be the high-water mark of the conflict. Amherst dispatched Bouquet and Col. John Bradstreet in the fall of 1764 to compel the tribes to accept terms of peace, which ultimately ended the fighting.

Pontiac died under suspicious circumstances five years later in the Illinois Country. His plan for an Indian Confederacy became an accepted strategy for resistance amongst the tribes in the Great Lakes region against white encroachment. Little Turtle, a Miami war chief, along with Blue Jacket, a Shawnee united the tribes in the 1790s and orchestrated the downfall of two U.S. armies until they were finally defeated at Fallen Timbers. One generation later, the Shawnee Tecumseh, along with his brother Tenskatawa unified the tribes and fought with the British during the War of 1812. Tecumseh’s alliance died with him at the Battle of the Thames in October 1813.