River Raisin National Battlefield Park, Monroe, Mich.

In 1812, as the United States and Great Britain spiraled toward another armed conflict, the Michigan Territory emerged as a critical theater of operations, its location north of Ohio (admitted to the Union in 1803) and its border with British-held Upper Canada made it an obvious avenue of invasion. American militias were called into service building preparatory roads even before the U.S. Congress declared war against Great Britain on June 18. With the ongoing war against Napoleon in Europe, few troops could be spared for service in North America, forcing British Major General Isaac Brock to depend on the cooperation of the Native American Confederation under the Shawnee war chief, Tecumseh.

American mobilization continued as Brigadier General William Hull, commander of the U.S. forces in the (Old) Northwest — accompanied by 1,200 Ohio militia and 200 regular soldiers — arrived in Detroit on July 5 and began preparations for the attack. Invasion of British-held present-day Ontario began on July 12. While Hull assailed the British at Fort Amherstburg, a small British force surrounded and took control of the unaware U.S. garrison at Fort Mackinac. Hull, unable to capture Fort Amherstburg or protect an overextended supply line that stretched back to Ohio, returned to Detroit in the first week of August.

Hull surrendered Detroit and the entire Michigan Territory on August 16 after a siege by British and Native warriors, knowing more Native warriors were enroute from the upper Great Lakes, and cut off from American support assembling at the River Raisin close to the Ohio border. The British and their Native allies were able to secure firm control over much of the Old Northwest as they pushed the frontier back to Fort Wayne, Indiana. Upon liberating Fort Wayne, Major General William Henry Harrison soon turned his sights on coordinating efforts to recapture Detroit. He established a base at the Maumee Rapids, south of present-day Toledo, Ohio.

In January 1813, these American forces were assembling for a winter campaign to retake Detroit. Revolutionary War veteran Brigadier General James Winchester, an early arrival, received a request from River Raisin settlers to lift British control of their community. Winchester dispatched more than 550 men from the 1st and 5th Kentucky Volunteer Regiments, under the command of Colonels William Lewis and John Allen to the River Raisin.

American efforts to outflank allied Canadian militiamen and Confederacy warriors proved unsuccessful, and the fighting dissolved into a series of fierce skirmishes through the dense woods to the north. In “the woods the fighting became general and most obstinate,” wrote one Kentuckian. “[T]he enemy resisting every inch of ground as they were compelled to fall back.” Over the course of two miles the slow-moving battle continued until darkness fell, with the retreating forces taking cover to fire on the pursuing Kentuckians, then dashing to another protected area before the pursuers could regroup or return accurate fire.

The victorious Kentucky Volunteers set up camp within the protection of the puncheon fence and French habitant homes. Upon word that the area was liberated, Winchester assembled four additional companies and proceeded to the River Raisin on January 20, 1813, bringing the number of American troops close to 1,000. Upon arriving, the 17th Infantry set up camp 200-300 yards outside the puncheon fence line in the bitter cold and deep snow. Meanwhile, the British and Native warriors prepared a counterattack across a frozen Lake Erie at Fort Amherstburg in Canada.

Second Battle at the River Raisin

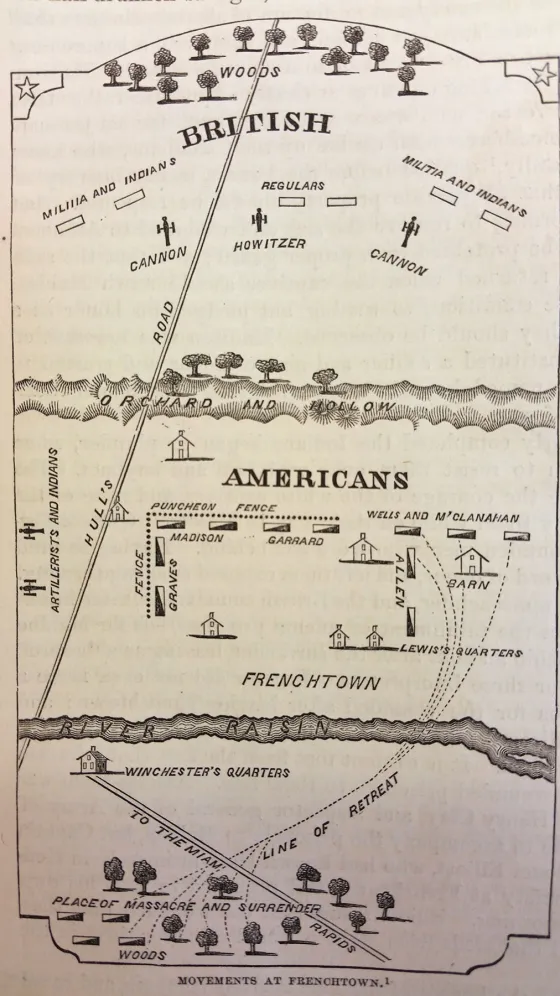

Arriving before dawn on January 22 and unnoticed by the American sentries, a force of 600 British Canadians and 800 Native warriors gathered into battle positions along the Mason Run creek, about 250–350 yards to the north of the settlement. British regulars and artillery were positioned in the center, a dispersed clustering of Native warriors made up mostly of Anishinaabeg (Odawa, Ojibwe and Potawatomi) and Miami, accompanied by some Canadian militia were to the west, and to the east was a large number of Native warriors, mostly Wyandot and Shawnee, in the forward position, supported by Canadian militia and artillery to their rear.

Reveille sounded, and an American sentry spotted the British in the pre-dawn light. He fired a shot into the forward line that killed the lead grenadier, and the report of his musket sent 1,000 just-awakened soldiers scrambling for their battle positions. Almost immediately, the British opened with their artillery and the infantry pushed forward from its center position. As they drew within range of the settlement, the infantrymen fired a powerful volley at what, in the still-dark distance, had seemed to be a line of soldiers. Assuming they had the advantage, the British made a fierce charge forward, but the target of their fusillade proved to be the puncheon fence behind which the protected Kentuckians could fire at will. With British artillery overshooting the mark, and the fence providing ample protection, the Kentuckians were unscathed and unrelenting.

Matters were quite different to the east, where the Canadian militiamen quickly adjusted the aim of their artillery and wreaked havoc on the exposed position of the U.S. 17th Infantry. As cannon fire tore through the encampment, the Regulars also had to contend with militiamen and Wyandot fighters who had taken possession of some nearby buildings from which they could fire at will into the American encampment. The Americans struggled to hold their ground, but eventually faltered when mounted warriors came around their right flank. An attempt was made to send a few companies of Kentucky militiamen to the aid of the 17th Infantry, but the effort proved disastrous.

General Winchester, arriving from his headquarters, ordered the infantrymen to fall back to the north bank of the river where they could rendezvous with the Kentuckians. Together they made a brief stand, but were soon overwhelmed by the pursuing Canadian, Wyandot and Shawnee fighters. After a frantic retreat to the south side of the river and another futile stand, the American position disintegrated entirely. Within 20 minutes, about 220 U.S. soldiers were killed and another 147 captured. Only 33 American Regulars managed to escape back to the Maumee River.

But the actions east and south of Frenchtown barely registered for the British Regulars and the Kentuckians still entrenched behind the fence lines. Instead, they remained locked in what seemed to be the main battle area. Over the course of two hours, the British regrouped and made two more frontal attacks, but the Kentuckian position was too strong — British losses were perhaps four times greater than those suffered by the entrenched Kentuckians.

As the British pulled back and evaluated their seemingly weakening situation, they received revelations about the status elsewhere. Winchester, now a prisoner of war and unable to give orders to those still engaged, arrived in the area. When told that his men would otherwise be burned out of their position and attacked by a much larger force of Native warriors, he agreed to send a message encouraging the Kentuckians still within the pickets to surrender. When they received the message, the riflemen Kentuckians balked, feeling themselves still able to carry the day. As Private Elias Darnell later recalled, “Some plead[ed] with the officers not to surrender, saying they would rather die on the field!”

These were brave words, but the Kentuckians’ position was dire. Their ammunition was low, they were completely hemmed in on the south, British artillery was in position to fire volleys of gunfire through their defensive lines and Confederacy warriors were firing into the heart of the settlement while preparing to set it on fire. In short, Major George Madison of the Kentucky 1st Regiment had two choices: to surrender to the British or, as he put it, “be massacred in cold blood.” Still, Madison was committed to holding out long enough to influence the terms of surrender. After some back-and-forth with the British over the disposition of prisoners, protection from Confederacy forces and care of the wounded, Madison formally capitulated.

Expecting American reinforcements from General Harrison’s troops, the British quickly withdrew due to heavy casualties. The battle was costly for the British Regulars and Canadian militia, but for the Americans it was an unmitigated disaster: Of the 934 who had heard the morning’s reveille, 901 were either dead, wounded or prisoners of war.

A National Calamity Turned Rallying Cry

When the British departed, they left the Americans who were too wounded to walk in the homes of the French inhabitants under a small guard of British troops. On January 23 in retaliation for past brutalities, Native warriors returned to the River Raisin to plunder and burn homes, killing and scalping many of the remaining Americans and taking others captive. Official U.S. estimates of the aftermath include a dozen named individuals killed and up to 60 more who were probably killed in this manner.

The event that became known as the “River Raisin Massacre” was not a sudden burst of collective violence. Rather, it began as a somewhat incredulous confirmation that no U.S. forces had arrived, then progressed to a deliberate taking of valuables and able-bodied captives that was later punctuated by the killing of the most severely wounded survivors. As Dr. Gustavus Bower later described what transpired, “They did not molest any person or thing upon their first approach, but kept sauntering about until there were a large number collected, (one or two hundred) at which time they commenced plundering the houses of the inhabitants and the massacre of the wounded prisoners.”

Even then, the killings followed a method that — however brutal — might be described as utilitarian. The wounded who could not travel were the primary victims, and they were killed swiftly. The looting, the taking of able-bodied prisoners and the burning of buildings and structures were done methodically — Dr. John Todd, a surgeon with the Kentucky 5th Regiment Volunteer Militia later described these actions as a kind of “orderly conduct.” This deliberateness of behavior did not diminish, and perhaps intensified, the horror many survivors later described. Indeed, the most vivid recollections related to the systematic nature of the killings and treatment of the remains.

The battle ended in what was described as a “national calamity” by then Major General, and later president of the United States, William Henry Harrison. It also left an impact on the broader American consciousness. The Americans who pushed north to liberate Detroit went on to destroying the British-Canadian-Indian coalition in the west at the Battle of the Thames, near present-day Chatham, Ontario, on October 5, 1813. Fueled by the battle cry, "Remember the Raisin!" their massive victory sealed the War of 1812 in the western theater for the United States, claimed the life of the great Shawnee leader Tecumseh, and resulted in the end the American Indian Confederation. In an even broader sense, the aftermath of these battles resulted in the implementation of U.S. policy of Indian removal from the Northwest Territory at the conclusion of the War of 1812, leading to the Indian Removal Act of 1830, a policy that continues to resonate today

Related Battles

934

182