As he walked down a White House corridor en route to a meeting with President Abraham Lincoln and his Cabinet on June 29, 1861, Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell had no way of knowing how dramatically the next 23 days would change his life and the lives of thousands of others, transforming the course of the young Civil War. Well regarded by his peers — including the venerable Winfield Scott, general-in-chief of the Federal armies, on whose staff he had once served — the 42-year-old McDowell was a career Army officer. But, despite his decades of military service, the newly minted commander of the Department of Northeastern Virginia, like so many officers of 1861, had never led a large body of men in combat.

While Lincoln and his Cabinet members listened, McDowell laid out a plan to attack the 24,000-man Confederate Army under Gen. Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, deployed near the winding Bull Run creek about 25 miles southwest of Washington. The general intended to use about 30,000 troops in the effort, marching in three columns, while another 10,000 men were held in reserve. With such numerical superiority, it appeared McDowell would overwhelm his Southern counterpart. Meanwhile, the 15,000 Federal troops under aging veteran Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson stationed in the lower Shenandoah Valley were tasked with preventing a Confederate force of about 11,000 men under Gen. Joseph Johnston from slipping out of the Valley and reinforcing Beauregard near the vital rail link of Manassas Junction. It was a complex plan, especially for an inexperienced army, and even McDowell had reservations about taking the offensive. Although some of Lincoln’s advisors questioned Patterson’s ability to hold Johnston in the Valley, the plan was ultimately approved.

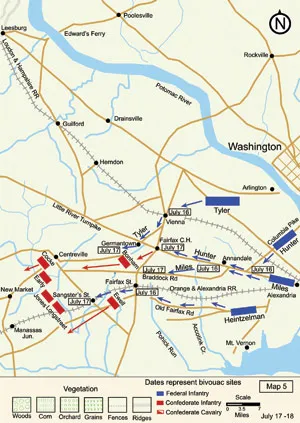

On paper, it was a solid, if ambitious plan; but, in practice, a number of factors were working against McDowell. Available maps were woefully inadequate, leading to mistakes in march routes and distances. The troops were green and undisciplined, and the complex plan required a level of precision marching and coordination challenging to a veteran army. Pressed by political rather than military considerations, McDowell’s army started west on July 16, making slow but steady progress toward its rendezvous with Beauregard.

As the federal column composed of Brig. Gen. Daniel Tyler’s division approached Centreville at midmorning on July 18, its commander decided to continue south toward Bull Run after local citizens told him about Rebels in the vicinity. Taking Col. Israel Richardson’s brigade with him, Tyler encountered Confederate Brig. Gen. James Longstreet’s Virginia brigade on the opposite side of the stream. Fighting erupted and continued for the next several hours, with neither side gaining a clear advantage. Knowing he had exceeded his orders, Tyler pulled out after a combined loss of about 150 men. This skirmish at Blackburn’s Ford offered a preview of the fighting to come; Tyler and Richardson had pushed their units into combat piecemeal, with each defeated in turn.

Although minor, Tyler’s engagement had a profound effect on what transpired three days later. Blackburn’s Ford eroded McDowell’s confidence in one of his most experienced subordinates and may have led him to again question the readiness of his army just as it was about to be committed to serious battle. The fight at Blackburn Ford, together with his own reconnaissance on the Confederate right flank, convinced McDowell that his chances for success were better if he employed a flanking movement around the Confederate left. McDowell dispatched his chief engineer, Maj. John Barnard, to find a suitable crossing area to flank his opponent. Although hampered by poor maps and a desire to avoid detection, Barnard found a route to Sudley Ford and surmised another to Poplar Ford. Once he informed McDowell of his observations on July 20, planning began in earnest.

Meanwhile, in the Shenandoah Valley, Gen. Joseph Johnston’s Southerners were moving across the mountains to reinforce Beauregard. Largely because of Patterson’s inaction, the normally cautious Johnston marched to Piedmont Junction, where his troops boarded cars on the Manassas Gap Railroad. Beginning about 8:00 a.m. on July 20, a steady stream of Southern troops began arriving at Manassas Junction, utterly unbeknownst to McDowell. Brig. Gen. Thomas Jackson’s Brigade was the first to make the trip. Before the battle would end the following day, three additional brigades from the Shenandoah Valley would reach the field and play a key role in defeating McDowell.

McDowell’s plan was as audacious as it was complicated. While Tyler’s division demonstrated in front of the enemy at the Stone Bridge on the Warrenton Turnpike and Blackburn’s Ford on the Union left, two divisions under the command of Brig. Gen. David Hunter and Brig. Gen. Samuel Heintzelman would undertake a flanking movement to envelop the Confederate left flank and crush it. But first, the troops had to get into position. McDowell wanted his men on the march to Sudley Ford in the pre-dawn hours of July 21. Such a maneuver might have worked for hardened veterans, but these were green troops with little or no marching experience.

Tyler had his men up at 2:00 a.m. and on the march 30 minutes later. Groggy from little sleep, the column made fitful progress in the inky blackness, further hampered by a large and cumbersome three-ton Parrott cannon. Somewhat inexplicably, McDowell did not put the two-division flanking column, which had farther to go, at the head of the column, instead placing Hunter and Heintzelman behind Tyler. Crossing Cub Run, the flanking column turned right down a narrow lane at the Widow Spindle’s farmhouse.

The pace of the march improved quickly, but the men still had 12 miles to cover before reaching the ford.

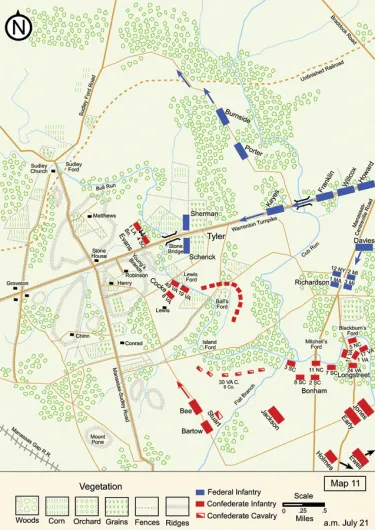

Meanwhile, Beauregard was forced to scatter his brigades along the banks of Bull Run, defending the numerous fords available to McDowell’s army. Only Col. Evans’s small brigade guarded the vital Confederate left flank at the Stone Bridge. His force consisted of the 4th South Carolina and 1st Louisiana Battalion, two cannon and two cavalry troops. These 1,100 men, most hidden behind Van Pelt Hill with a skirmish line near the bridge, were all that stood between Beauregard’s main army and three Federal divisions.

Once Tyler reached his assigned position in front of the Stone Bridge his artillery opened fire, while Richardson created a diversion in front of Blackburn’s Ford. But as an hour passed and no attempt to force a passage across the stream came, Evans wondered what his enemy was up to. About this time he received a message from the Confederate signal station several miles away that informed him, “Look out for your left, you are turned.” The men on the heights had glimpsed the sun bouncing off Federal muskets as Hunter’s and Heintzelman’s men made their flanking movement.

The lead brigade in Hunter’s division belonged to Col. Ambrose Burnside, who would eventually command the Union army during the Fredericksburg Campaign in late 1862. When they splashed across Bull Run at Sudley Ford about 9:30 a.m., almost three hours behind schedule, the Confederates were waiting for them.

Leaving but four companies of the 4th South Carolina to keep an eye on Tyler, Evans quickly moved his men to face this new threat, eventually positioning them on the rear slope of Matthews Hill. The 1st Louisiana Battalion arrived first and its skirmish line engaged its counterpart of the 2nd Rhode Island. The balance of the 4th South Carolina then came up, but, in the confusion, fired into the backs of the Louisianans. Incensed, the Creoles turned and fired back at the South Carolinians until officers ended the friendly fire fiasco. Seeing confusion in the Yankee ranks atop the hill, the Louisianans attacked, only to be driven back by the combined musketry of the 1st and 2nd Rhode Island. The confusion probably resulted from the 2nd Rhode Island sliding to its left to provide room for its sister regiment.

Reinforcements arrived for both sides. Brig. Gen. Bernard Bee, commanding his own brigade and exerting control over Col. Francis Bartow’s as well, halted his command on Henry House Hill. Impressed by its defensive possibilities, Bee rode down the hill to encourage Evans to abandon his position on Matthews Hill and join his command on Henry House Hill, but despite the growing host of enemy soldiers on the crest of the hill, and the repulse of the charge of his 1st Louisiana Battalion, Evans refused to budge. His refusal left Bee with little choice but to send down his 4th Alabama, followed by the rest of his two brigades.

Confusion also reined on the Federal side, as units did not move where ordered or did not respond to orders quickly enough. Eventually, Burnside put his entire brigade on the firing line and gave battle to Evans, Bee and Bartow. Flanked on his right, Bee was forced to pull his defeated units out of combat. The retreat was anything but orderly, and the survivors milled about as their officers attempted to reform the shattered units.

Col. Andrew Porter’s Union brigade next took up the fight. Like Burnside’s before them, Porter’s regiments were sent in piecemeal and defeated in succession. Because of the effective fire of Capt. John Imboden’s battery, perched atop Henry Hill, Porter’s regiments were unable or unwilling to follow Bee’s disorganized Confederates. Instead, they veered to the left and made their way along the Warrenton Turnpike where they were battered by the remnants of Bartow’s Brigade and Col. Wade Hampton’s Legion near the Robinson homestead.

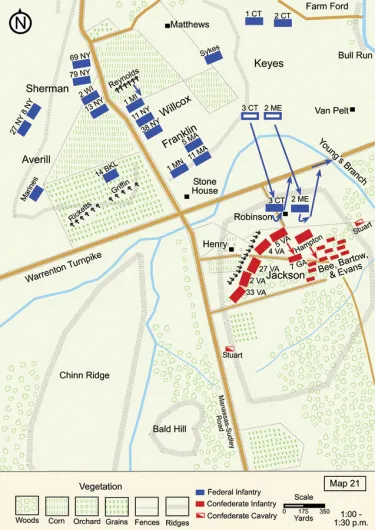

No sooner had Brig. Gen. Thomas Jackson’s Brigade arrived on Henry Hill and taken up position just behind the slope than two regiments of Brig. Gen. Erasmus Keyes’s Federal brigade advanced up the hill, passing the Robinson House and audaciously attacking the 5th Virginia and Hampton’s Legions, both of which were forced to retreat into the woods behind them. The Southern setback was but momentary, for the Virginians and South Carolinians trained their muskets on the exposed and unprotected Northerners and forced them to abandon the hill and return to the Warrenton Turnpike.

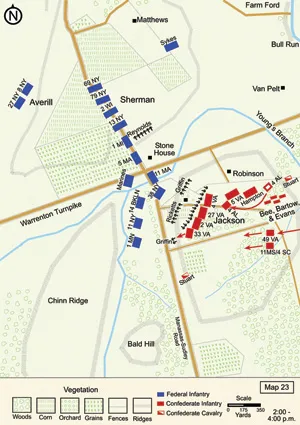

Maj. William Barry, commander of the Federal artillery, changed the face of the brisk and spreading battle around 2:00 p.m., when he ordered Capt. James Ricketts and Capt. Charles Griffin to redeploy their unsupported batteries on Henry Hill, despite their vehement objections. Much of the remainder of the battle involved a desperate struggle to capture or recapture these ill-fated cannon. The Confederates brought up their own field guns and the two sides slugged it out at close range, while Jackson’s men waited, protected on the opposite side of the hill.

Frustrated by his inability to make headway against the Confederates on Henry House Hill, Griffin moved some of his guns around to the enemy’s left flank. It was a dangerous and bold move, for which Griffin paid a terrible price when the 33rd Virginia advanced and captured both pieces. During the remainder of the battle, four Union regiments and seven Confederate regiments would fight over these guns.

Farther north, Ricketts’s guns were deployed just south of Judith Henry’s home, where they attracted considerable attention from the infantry of both armies. They were initially captured by the 4th and 27th Virginia regiments (Jackson), then recaptured by the 5th and 11th Massachusetts, only to be retaken by the 5th Virginia and Hampton’s Legion. A succession of Federal regiments, including the 13th New York, 2nd Wisconsin, 79th New York, 38th New York and 69th New York launched independent attacks on the guns, but most failed miserably. The latter two regiments finally attacked up the hill in some semblance of an organized assault and finally drove the two Rebel regiments away from Ricketts’s guns. They would not hold them for long, however, as three fresh Confederate regiments from Col. Philip Cocke’s Brigade, which had been guarding Ball’s and Lewis’s Fords, reached the area and stormed across the open plain to recapture the guns.

McDowell and his inexperienced commanders had not handled their men well. Although they outnumbered the Confederates and were better equipped, most regiments were sent in piecemeal and so beaten in turn. It didn’t help matters that several of the regiments wore gray uniforms, which invited confusion and friendly fire.

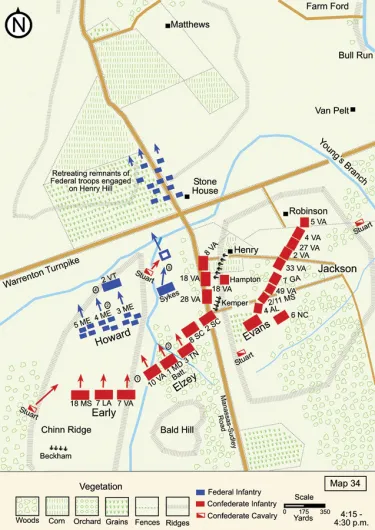

The last major action of the day unfolded on Chinn Ridge about 4:00 p.m., when McDowell sent his final fresh brigade under Col. Oliver Howard sweeping south. The brigade’s route might have taken it around to the vulnerable Confederate flank with potentially devastating results to the Southerners. Instead, a Confederate brigade under Col. Arnold Elzey, fresh off the trains from the Shenandoah Valley, fired into the unsuspecting Northerners and attacked, forcing the Federal troops to the rear. A horse battery also hastened Howard’s retreat.

The Federal army’s retreat, initially calm and well organized, became less so with fears of Confederate cavalry and accurately aimed cannon fire. Hundreds of men were scooped up, including Congressman Alfred Ely from New York. Most of the troops finally found their way to safety, depressed and worn out by their long day.

By later standards the losses during the day-long battle were modest; Union casualties amounted to about 2,700, with 1,900 more in the Confederate ranks. Still, the campaign provided important lessons to both sides, including a more sobering and realistic sense that the war would be long and bloody. It was truly an end to innocence.

Related Battles

2,896

1,982