By Sam Smith and Ina Dixon

The American Civil War is undoubtedly one of the most evocative military conflicts in history. Contemporary enthusiasts can find echoes of the struggle almost everywhere: in veterans’ words preserved in corner rooms of dusty bookstores, in the monuments that fill hometown cemeteries and parks, and in the fields, forests, and hillsides that bear silent witness to a generation’s sacrifice.

This array of historical talismans is not the product of one mind, one committee, or one agreed-upon narrative. It is instead a sedimentary evolution, in which layers of interpretation are added and diluted according to the fashionable fascinations and blinders of their time.

In the late 1800s, the Civil War was well within living memory, a horrific but profoundly important part of the American consciousness. At the same time, although veterans were eager to tell their stories, there was no website, film, or video game to slake the public’s desire for visceral, almost-real-life experience. In this context, reverence for the great struggle took perhaps its most spectacular form in the creation of “cycloramas.”

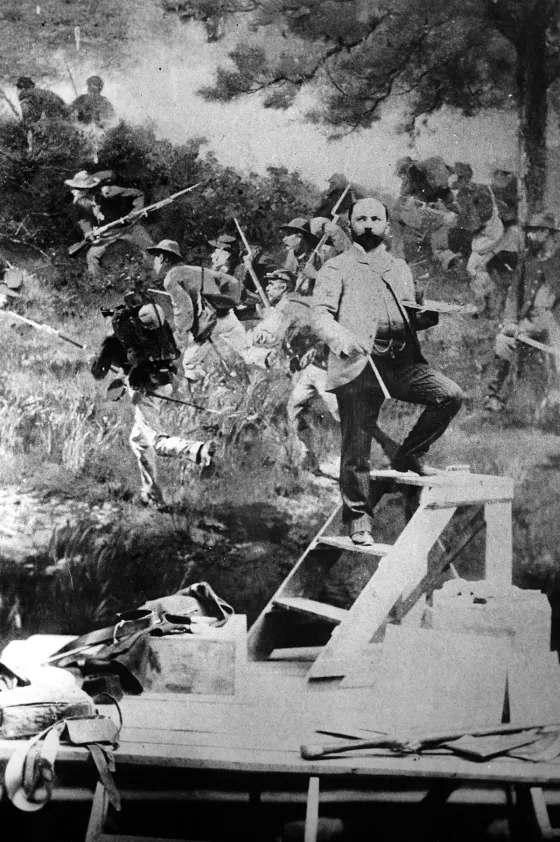

Cycloramas were unlike any other memorial to the Civil War. The massive panoramic paintings, usually 50 feet high and at least 400 feet in circumference, were hung in a 360 fashion that allowed visitors to seemingly step inside of a battle in progress.

Cycloramas became circus-like attractions that toured the United States and entertained thousands with all-encompassing depictions of the greatest battles of the Civil War -- Shiloh, Gettysburg, Vicksburg, Missionary Ridge, Atlanta -- all of which could be re-lived, refought and remembered by veterans and the public alike. Crowds flocked to cycloramas’ elaborate displays in order to witness, on a lavish scale, the grandest art of war.

Promising a high level of accuracy through on-the-ground research and studies of photography, cycloramas offered viewers a realistic and grand portrayal of the war’s most famous battles. Grey-bearded veterans would often weep upon seeing their memories brought to life on canvas.

Emotional outbursts from veterans and the general public was the effect desired by the teams of ten to fifteen artists whose brushstrokes outlined the boom of bursting shells, the clash of desperate swords and the deathly moans of dying men.

These vivid depictions of battle were complemented by a lecturer who would narrate the painting for spectators. From their viewing platform in the middle of the painting, spectators were entertained not only by the painted battle, but also by their lecturers, who were often Civil War veterans.

The lecturers mixed in their own tones of memory, regret, and zeal as they described the generals, the troop movements and the action of the scene portrayed on canvas. Lecturers’ memories softened and embellished the experience of war and lent meaning to Americans seeking to find their heroic selves in a new and difficult world.

Entertainment, history, and folklore all comingled for the Americans who went to see these dramatic paintings. Encompassed within the scene of battle, spectators found themselves reliving, not just remembering, a grand and bloody war between brothers.

Other sites of memory did not match the cyclorama’s dynamic portrayal of battle. The stone soldiers that peppered cities and towns simply held their posts, occasioning only reverential remembrance of our great war. Printed histories and memoirs could barely compare to the personal and sensational entertainment precipitated by the cycloramas.

The cyclorama craze indicates that Americans wanted to commemorate the Civil War not only in silent statues or sentimental prose, but also by bringing battle and suffering back to life in idealized glory. Narrated, artfully crafted and all-encompassing, the panoramic paintings made the war awesome and seemingly real for the American public.

Cycloramas always depicted Union battle victories. As Americans crowded the viewing platforms of Cycloramas around the country, memory became tradition and tradition became responsibility: to uphold an inseparable, inevitable and everlasting Union, dedicated to liberty and consecrated with blood.

Such a grand purpose could only be forged in fire and could not be fully understood through cold and silent statues. Rather, the popular mind was shaped by the massive, romanticized and vivid experience of the cyclorama.

Though motion pictures have updated and intensified the cycloramic experience, cycloramas are not lost to history. At the Gettysburg Cyclorama in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, you can step inside the final moments of Pickett’s Charge at the Bloody Angle. In Atlanta, Georgia, the Cyclorama of the Battle of Atlanta awes with its sweeping portrayal of a balmy and bloody July day in 1864. Cycloramas like these still carry immense and unique power for those seeking to not only remember the Civil War, but also to consider the meaning behind our commemorations.

Learn More: Civil War Casualties

Related Battles

13,047

10,669

23,049

28,063

4,910

32,363

5,824

8,000

3,722

5,500