Photographed here in the 20th century, the Adams mansion was built in 1731 and became the residence of the Adams family for four generations. Home to President John Adams and first lady Abigail Adams, the preservation of this home and the artifacts inside ensures that the Adams family's legacy will live on.

The story of the Adams family is the stuff of American legend, rightfully so. There is, however, far more in the people and events they participated in that make their true stories so enthralling to the rest of us. How is it that this esteemed family from what was formerly Massachusetts Bay became the original American political dynasty? Two presidents, a Secretary of State, a noted historian, several revering wives to match, and the man credited with sparking the Revolution. Without question, they remain the ascendance of one of the finest political families in American history.

The Adams arrived in the New World with some of the very first English settlers. Henry Adams, the family patriarch who arrived in the 1630’s from Somerset, England, likely came as a Puritan religious dissenter from the Church of England. Religion certainly held an important place in the family’s life, as many of Henry’s descendants worked as ministers in the town of Braintree where they eventually settled.

It is impossible to discuss the American Revolution, and its origins, without acknowledging Samuel Adams. Among his peers of the day, he was admired for his spirited oratories and advocacy for liberty. In the 1760s, like nearly everyone in Boston, Adams had been a devoted British subject. The passage of the Stamp Act in 1765, and the increasing presence of British troops in Boston, however, threw Adams into the emerging bands of protestors and propagandists. It is difficult to know exactly what he participated in, and what constitutes pure fiction. We know that he was a founding member of the Sons of Liberty, whose sole purpose was to incite visible pushback against British taxation. The group intimidated tax collectors and encouraged public demonstrations calling for the repeal of each new legislation enacted by Parliament. Adams became a leading figure in the colonial movement to petition Parliament to repeal all of the recent tax measures. In response to his petitions, Parliament sent troops to Boston in 1768. It is not known if Adams was present on King Street the night of March 5, 1770, to witness the Boston Massacre, despite some movies and stories portraying him in the thick of the mob. He supported the trial of the British soldiers and supported his second cousin John Adams’ decision to defend them. There also isn’t any evidence that he was present in the group that allegedly dressed up as Native Americans and tossed barrels of tea into the harbor in December 1773 during the Boston Tea Party. What is certain is that he used the events of the Boston Tea Party in the press to push for colonial autonomy from British control. However, there remains a dispute whether he was advocating for reconciliation or complete independence prior to 1775.

Adams and his younger cousin John were nominated to attend the First Continental Congress in September 1774. After an inconclusive round of meetings between the other colonies, Massachusetts continued on the path of escalation with British authorities. Sam Adams, along with John Hancock, were soon wanted men by British general and military governor of Massachusetts Thomas Gage for inciting the countryside into insurrection against the Crown. In April 1775, while in hiding, British forces marched west to seize stored munitions at Concord, and arrest the two leaders. The events that unfolded would trigger the start of the American Revolution. Adams and Hancock both served as delegates at the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia in May 1775. Though neither as popular or well-known as Samuel, it was John Adams that took the reins and became the loudest advocate for Massachusetts and then independence the following spring. The elder Adams played roles in the drafting on the Articles of Confederation in 1777 and its replacement in 1787-88 with the US Constitution. He served as Lieutenant Governor and Governor of Massachusetts during the 1790s before retiring and passing away in 1803.

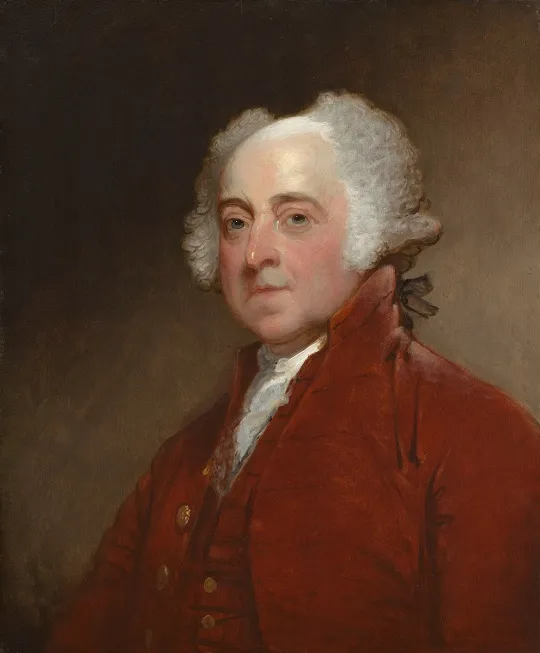

As the war continued, Samuel Adams’ star began to fade, while that of his cousin’s continued to climb higher. John grew up in the town of Braintree where his ancestor settled, and where his father, John Sr., was a popular deacon and member of the community in the early decades of the eighteenth century. The Adams family of Braintree held good standing among the townsfolk, and young John found himself following in his father’s footsteps by attending Harvard College. Despite his father’s wishes of becoming a minister himself, young John studied law and began practicing by the time of his father’s death in 1761. Throughout the 1760s, Adams showed a promising career as a lawyer as well as a man of deep political convictions. He penned several pamphlets defending certain aspects of case law, and generally defended British authority, but he publicly denounced aspects of the Stamp Act of 1765, arguing people could only be taxed by their elected representatives. It was in 1764 that Adams married Abigail Smith, a woman who was his intellectual equal and became his “dear friend” for the next fifty-four years.

His rise to international fame culminated with the events of the Boston Massacre. Following the events and the public’s outcry over the legal rights of the accused British soldiers, Adams took on the case in the soldier's defense. The court eventually found Captain Thomas Preston and his men not guilty of murder, giving Adams a very public legal victory. It won him the admiration of British Loyalists. However, he may have felt regarding British Parliamentary authority to tax the colonies without their consent, Adams remained a staunch British subject. This changed following several events in the next few years. Changes in the way Royal appointed judges and officials were paid from colonial pockets angered Adams, and the continual escalation of attacks on British authority - which spurred retaliatory efforts at the expense of Boston citizens - led Adams to change his mind about allegiances to Parliament. When his cousin, Samuel Adams, leader of the Sons of Liberty, organized the gathering of delegates from all of the colonies to discuss how to address the rising hostilities, John was nominated and attended.

We know that John Adams played significant roles in the events that followed. Perhaps he played the most crucial role at various moments that otherwise would have drastically changed the events of history. It was Adams who stood forward and nominated George Washington, a Virginian, to lead the new continental armed forces, in June 1775. It was Adams who punted the responsibility of writing the Declaration of Independence to a young Thomas Jefferson, whom Adams believed to be a superior writer and equal intellect of the Lockean mind. We know that it was John Adams, who upon the Second Continental Congress receiving Jefferson’s revised draft, stood before the delegates on the evening of July 1, and gave a rousing speech - during a fateful thunderstorm - that summed up their long, hard-fought arguments for justifying complete separation from Great Britain. “The time is now!” he reportedly shouted.

If he had dropped dead the following day, his place in American history would have already been cemented. But, John Adams of Massachusetts was not finished. He went on to serve in many key committees during the American Revolution, often conflicted over the war’s direction, and how best to manage a Congressional body incapable of assisting the army. He, along with his young son and protégé, John Quincy, sailed for France in 1777, and joined in the company of top diplomat Benjamin Franklin in the French Court. Adams and Franklin, who had respected each other’s passion for independence, came to disagree over each other’s methods of diplomacy. Adams found himself isolated compared to the celebrity status of Franklin and left-over disagreements he had with the French minister. Instead, he became the minister to the Netherlands and then played a role in finalizing the Treaty of Paris in 1783, officially bringing the war to an end and recognizing the United States of America as an independent nation. In 1785, Adams became the first Minister to Great Britain, and met King George III in person in a famous exchange of mutual respect and tacit acceptance. He returned to the United States in 1788 to a hero’s welcome in Boston, and soon found himself elected as Vice-President to the new federal government.

In New York, Adams stood aside on the balcony as George Washington was sworn in as the first President of the United States in March 1789. Though an advocate for Federalist policy and a defender of the Constitution, Adams found himself marginalized in his role as second to Washington. The vice-presidency had little to do in responsibilities, aside from presiding over the Senate, and Adams further felt isolated at often being left out of important cabinet meetings in the Washington administration.

In 1796, Washington retired for the second time in his life, leaving the presidency open to someone who wasn’t everyone’s first choice for the position. Adams narrowly won the election, and the runner-up, Thomas Jefferson, became his vice-president. Having been close friends for two decades, Adams assumed Jefferson would be a powerful ally. However, political differences soon ruptured the friendship, and Jefferson secretly undermined Adams in the newspapers.

Though Adams was a Federalist, others within the party, particularly those allied to Alexander Hamilton, viewed him with contempt. Adams had retained many appointments from Washington’s administration, and they worked to undermine his influence in shaping his own policies. President Adams was successful in keeping the United States out of war with France and England, formally dissolving the alliance with France after the XYZ Affair. He also chartered the creation of the modern American navy, including the construction of six heavy frigates like the USS Constitution. Lastly, his last hour appointment of John Marshall to the Chief Justice seat of the Supreme Court earned Adams what he considered his finest achievement as president. The Alien & Sedition Acts, which sought to, among other things, squash negativity directed at him in the press, however, overshadowed his other achievements. He lost the bitter election of 1800 to Thomas Jefferson, now ascendant in the new Democratic-Republican faction.

Adams and his wife, Abigail, retired to their farm “Peacefield” in Quincy, Massachusetts. The retirement was not without its tragedies. Their son Charles succumbed to alcoholism in 1801. Their daughter Nabby died of breast cancer in 1813. Abigail, always the rock of the family, and particularly to John, died of typhoid in 1818. The elder statesman afterward lived in the care of his youngest son, Thomas, and his grandchildren. Perhaps the most enduring part of his legacy began in 1812 when John began writing to his former friend, Jefferson. The two rekindled their friendship through a series of letters that spanned the rest of their lives and remain among the most cherished correspondence in American history. In 1824, the Marquis de Lafayette returned to America to embark on his grand tour in anticipation of the young nation’s fiftieth birthday. Lafayette met with Adams twice, and the meetings were said to have revived a youthful spirit in the elder patriot, now nearly the age of ninety. His health had been declining for years. He could no longer write as he hands constantly shook. In June 1826, he came down with a severe fever, and as the nation’s birthday approached, John Adams lay besieged with the gravity of a generation about to pass with him. Before he expired, on July 4, he whispered to his surrounding family, “Thomas Jefferson survives.” He was unaware that Jefferson, himself in poor health for years, had also passed away that same day. The fact that the two men who did perhaps more than any other Americans of the era to secure American independence died on the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration’s ratification has signified for many the special nature of our country, its founding, and the men who created it.

In the decades that followed, Adams’ reputation suffered from several poorly written biographies. Authors usually focused on his failures as president, the fact that he had only served one term, and that his well-known adversarial demeanor towards people showed he lacked the ability to handle the strains of public life. It seemed that Adams was destined to remain misbegotten among the scholars of American history. In the 1970s, with the bicentennial inspiring a new generation of historians to analyze the Founding Era, the revitalization of Adams’ legacy began. This culminated with the acclaimed biography by beloved historian David McCullough in 2001 that led to a successful television miniseries on HBO in 2008. However, most historians continue to stress that John Adams remains widely unknown to the American public.

As you can see, John Adams lived quite a life. But this story is about the Adams family, and so, we must look past one of America’s most important Founding Fathers. John and Abigail’s oldest son, John Quincy, was equally as ambitious and capable as his father. He is arguably the most accomplished American politician to ever live. Certainly, few future statesmen have boasted more accomplishments.

Born in 1767, the young Johnny was schooled from an early age to be the heir successor of his father’s legal profession. In June 1775, John Quincy, along with his mother and siblings, watched from a hill the British assault on Charlestown. Following the Declaration of Independence, John Adams was nominated to become a minister to France. John decided to take young John Quincy with him, where the boy would receive a French education and quite the world experience. (Brother Charles accompanied as well). In 1781, he served as the secretary to the American diplomat in the Court of Saint Petersburg. Upon returning to the United States, he finished second in his class upon graduating from Harvard in 1787. Initially, he followed his father’s footsteps and started his own law practice. But with the creation of the Constitution and the new federal government, John Quincy Adams was soon nominated to serve as one of President Washington’s foreign diplomats.

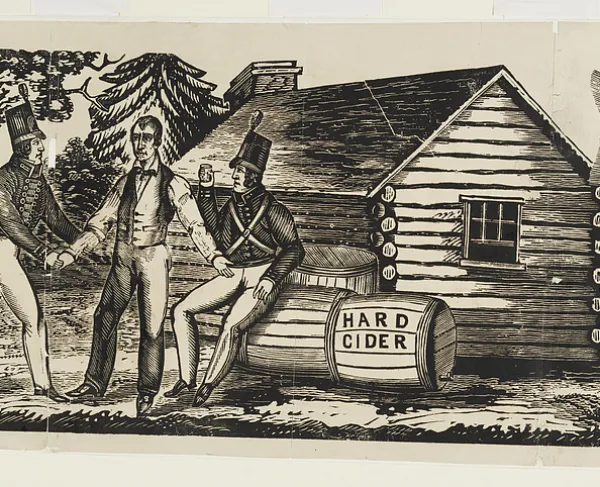

The eldest of the former president’s sons served as a Senator from Massachusetts during the Thomas Jefferson’s presidency but resigned after continued disagreements with members of the Federalist Party and his occasional support of Jefferson’s administration. He resurfaced as Minister to Russia under the administration of James Madison and participated in the peace talks with Great Britain during the War of 1812. Madison then appointed Adams Minister to Great Britain in 1815. He next served as Secretary of State under President James Monroe and is famously forgotten as the chief architect behind the Monroe Doctrine. The Adams-Onis Treaty also saw the US acquiring Florida and establishing the western boundary to the Pacific northwest. In 1824, Adams ran for the presidency and was perhaps the most qualified candidate of his generation. He faced off against the national hero of the Battle of New Orleans, General Andrew Jackson. A split of Electoral College votes among the top candidates caused the House of Representatives to ultimately decide the victor in the election. What became known as the “Corrupt Bargain” saw Speaker of the House Henry Clay deciding for Adams over Jackson. In return, Jackson’s supporters were furious when Adams appointed Clay his Secretary of State. Jackson and Clay had already become political enemies, but this result intensified their animosity towards each other.

The Adams administration was essentially ineffective. Despite campaigning on a robust national plan of expansion, he gained little support for his initiatives by his own party. Rivals who were still upset over the election refused to work with him, and all the while Andrew Jackson became more popular as he vowed to challenge Adams in the next election. In 1828, Adams lost reelection after a bitter campaign against Jackson. Historians have charged that though capable and extremely intelligent, the younger Adams suffered from the worst of his father’s personality traits, making him unpopular with the general electorate. Following this, Adams was elected to the House of Representatives in 1830 where he would perhaps cement his legacy of great American statesman in his quest to battle the forces of sectionalism, state’s rights, and the expansion of slavery into the western territories. He famously attacked a gag rule that Southern members of the delegation enacted in a bid to censor any abolitionist talk on the floors of Congress. He also famously defended the prisoners of the slave ship Amistad at their trial. His testimony ultimately helped win their freedom and acquittal. In February 1848, he collapsed from a cerebral hemorrhage at his seat in Congress while voting on the Mexican-American War. He died two days later inside the Capital Building. Though his tenure as president remains controversial, his years in the House of Representatives, and particularly his crusade to oppose slavery, have since won him praise from historians and scholars.

Like his father, the life of John Quincy Adams was not without its personal tragedies either. Depression and addiction seem to have had deep roots within the family bloodlines. In addition to his sister’s cancer and both of his brothers’ struggles with alcoholism, his eldest son, George Washington Adams, committed suicide in 1829 after suffering from the disease too.

John Quincy’s son, Charles Francis Adams, Sr., was a successful senator from Massachusetts before serving as President Lincoln’s ambassador to Great Britain during the Civil War. His son, Charles Francis Adams, Jr., served as an officer in the Union army during the Civil War and later became president of the Union Pacific Railroad. His other son, Henry Adams, was the noted historian of American history. Charles Sr. is also best remembered for building the first presidential library in the United States at Peacefield, Massachusetts, in honor of his father.

And we certainly cannot conclude our brief discussion of the Adams of Massachusetts without mentioning Abigail Adams, wife of John Adams, and perhaps one of the staunchest, and original feminists, in American history. Educated, intelligent, and ever opinionated, Abigail proved to be the perfect counterweight to her husband’s crash and blunt manner of personality. We remember her today for her insistence that the male members of the Continental Congress, “remember the ladies,” when going about constructing a new government. The avid writer, she and her husband penned a correspondence throughout their lives that is among the finest in American history.

Further Reading:

- The Letters of John and Abigail Adams By: John and Abigail Adams

- The Adams-Jefferson Letters: The Complete Correspondence Between Thomas Jefferson & Abigail & John Adams By: Lester J. Cappon

- The Lost Founding Father: John Quincy Adams and the Transformation of American Politics By: William J. Cooper

- Louisa Catherine: The Other Mrs. Adams By: Margery M. Heffron

- John Quincy Adams: American Visionary By: Fred Kaplan

- John Adams By: David McCullough

- Samuel Adams: A Life By: Ira Stoll

- John Quincy Adams By: Harlow Giles Unger

- Henry Adams and the Making of America By: Garry Wills

- Dearest Friend: A Life of Abigail Adams By: Lynne Withey

- Friends Divided: John Adams and Thomas Jefferson By: Gordon S. Wood