The treason of Benedict Arnold during the Revolutionary War is one of the most infamous events in American history. The courageous Continental general’s downfall, however, is often times misunderstood or overly simplified. There were many reasons behind his turning coat, including his marriage to the young Philadelphia socialite, Margaret “Peggy” Shippen in 1779. Here are ten facts about the Arnolds and the plot to betray America.

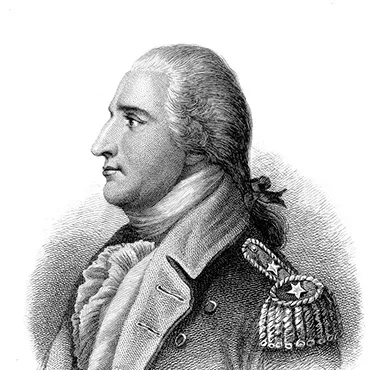

Fact #1: Major General Benedict Arnold was one of the best, if not the best battlefield commanders in the American Army during the early years of the Revolutionary War.

Since the beginning of the conflict, Benedict Arnold was seemingly always in the thick of the fighting and found himself at the forefront of many of the War’s early heroic moments. He rose in the ranks from colonel to major general, albeit a much slower rise than he deserved. Arnold assisted in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga and Lake Champlain in 1775, was wounded during the epic assault on Quebec City, slowed down an invading British army from Canada at Valcour Island in 1776, and resisted an enemy raiding party at Ridgefield, Connecticut, earning a strategic victory for the Patriots in the spring of 1777. Later that year, he valiantly led troops at the Battles of Saratoga, and without a command, successfully delivered the knockout blow against John Burgoyne’s army during the second of those engagements. On multiple occasions, Arnold received little to no recognition for his heroism and exploits, and instead, watched as others with less experience and capabilities were constantly promoted instead of him.

Fact #2: Margaret “Peggy” Shippen was the daughter of Edward Shippen, a Philadelphia lawyer, and was accustomed to upper-class life in the city’s high society.

Born on July 11, 1760, Peggy was only a teenager when the delegates to the First Continental Congress traveled to Philadelphia in 1774. The delegates were entertained by her father, Edward, a moderate loyalist who remained neutral during both the American and British occupations of the city throughout the War. Peggy, however, was friends with many staunch loyalists and was enchanted by the high-class entertainment and parties held by British officers. She became friends with many of the young gentlemen when they garrisoned the city in the winter of 1777-1778. After the army’s evacuation in June 1778, Peggy longed to return to that lifestyle.

Fact #3: Arnold was appointed Military Governor of Philadelphia by George Washington after the British Army evacuated the city in June 1778.

During the battle of Bemis Heights on October 7, 1777, Arnold was grievously wounded in his left leg, the same that was struck while he assaulted Quebec in 1775. It took multiple surgeries and months of recovery in an Albany, New York hospital for him to resume service, and he would forever walk with a limp, the left leg two-inches shorter than the right. Arnold suffered from too much pain to ride a horse or lead troops in the field, therefore, George Washington appointed Arnold military governor of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania following the British evacuation. He arrived in the city on June 19, 1778, and took up residency in the Penn Mansion (later known as the President’s House) on Market Street.

Fact #4: While serving in Philadelphia, Arnold was despised by members of Pennsylvania’s radical governing body, the Supreme Executive Council.

When the British evacuated Philadelphia, the Continental Congress and Pennsylvania’s Supreme Executive Council returned to the city to resume business. The radical state governing body did not appreciate most of Arnold's actions while he was military governor. They did not like his attempts to live a lavish lifestyle, riding in fancy carriages (Arnold still could not walk or ride) and attending the theater and parties, sometimes with the city’s loyalists. In February 1779, Joseph Reed, President of the Executive Council, brought multiple charges against Arnold for shady business dealings and abuses of power. The charges, which included favoritism and using state-owned wagons to transport his own goods, were debated by a special committee of Congress. They absolved Arnold of all charges other than a few, but recommended that the case be turned over to the Army. After much delay as well as efforts by George Washington in favor of Arnold to remain patient to restore his reputation, in December 1779, the court-martial did not charge the General on any account. They did, however, recommend that Washington issue a reprimand, which he did. Arnold correctly believed that Washington was his greatest ally; therefore, the reprimand was more than he could bear. This was the final slight to his honor that Arnold would tolerate.

Fact #5: Arnold opened up a line of communication with British General Sir Henry Clinton only a month after he and Peggy were married.

Peggy Shippen was well-regarded as the most beautiful woman in all of Philadelphia, and she caught Arnold's eye immediately. In early 1779, after becoming military governor, Arnold began courting the young Shippen girl, who was then 18-years-old. Her father was reluctant at first to the idea of their marriage, but he eventually conceded, and the couple wed on April 8, 1779. The Continental Army’s chief of artillery, Henry Knox, wrote, “Our friend Arnold is going to be married to a beautiful and accomplished young lady, a Miss Shippen, of one of the best families in [Philadelphia].” It was a happy moment for Arnold, who had lost his first wife, another Margaret, to sickness in 1775. A month after their wedding, Arnold, using local loyalists, sent a letter to New York City for British General Henry Clinton, offering his potential services to the Crown. Contrary to popular myth, the British did not initiate communications with the American general, and did not seduce him with gold.

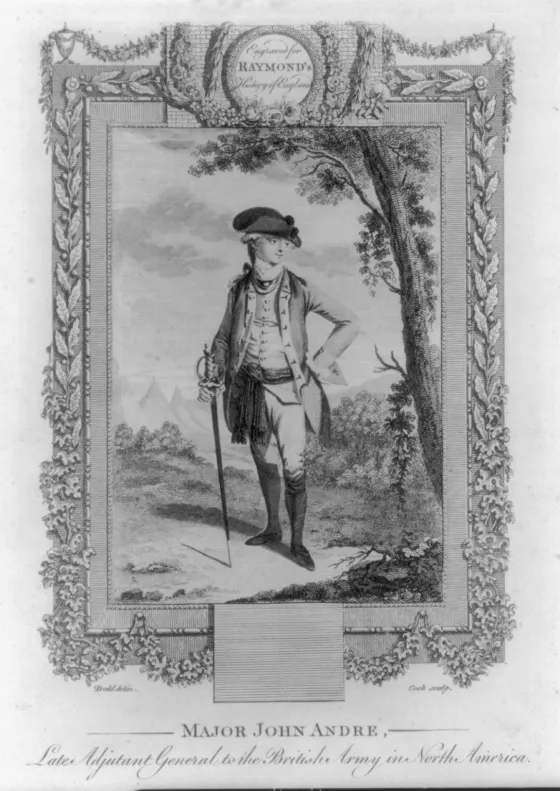

Fact #6: Major John André, the British army’s adjutant general and chief intelligence officer, served as the liaison between Arnold and Clinton.

While communicating with the British high command, Arnold was in direct contact with British Major John André, an up-and-coming officer who earned a reputation in Philadelphia during the occupation. He was a man of the arts, a social butterfly, and a gentleman, and he earned the respect of both his peers and American officers he met. He had also formed a friendship with many of the young women in Philadelphia, including Peggy Shippen. While it is possible that he may have briefly courted her, it never amounted to anything, other than providing André with a direct link to Benedict Arnold.

When communications between Arnold and André commenced, the two utilized invisible ink and coded messages. The codes were written in-between the lines of seemingly normal letters. When received and made visible, the codes were deciphered using a book called Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England. Each word of the message would be written in three numbers that directed the recipient to a specific page, line, and the word in the book to use.

Fact #7: Local loyalists and members of Peggy’s social circle helped deliver Arnold’s messages into British-held New York City.

Arnold could not directly deliver his messages to the British himself, nor could he trust a Patriot courier to ride to New York City with such incriminating documents. Because of this, he utilized Peggy’s inner-circle of friends, suspected loyalists in Philadelphia, and others recommended to him by John André. The letters would be passed from person to person and then given to someone who was capable of getting into New York City. Joseph Stansbury, a local merchant, carried the first letter, in which Arnold confessed, “under a solemn obligation of secrecy, his intention of opening services to the commander-in-chief of the British forces.”

Fact #8: Arnold was given command of the crucial West Point defenses in New York’s Hudson Highlands in early August 1780.

Rather than seeking an active command in the field after he recovered enough to lead troops in battle, Arnold lobbied George Washington to place him in charge of the Hudson Highlands’ fortifications and West Point. Washington was unaware that Arnold had informed the British that he was going to gain control of the strategic strongpoint, weaken its defenses, and coordinate its capture, giving the enemy possession of the Hudson River and dealing a devastating blow to the American war effort. On August 3, 1780, Arnold got his wish when Washington ordered him to “proceed to West Point and take the command of the Post, and its dependencies…” Arnold's plot was now set in motion.

Fact #9: When Arnold’s treasonous plan was uncovered, Peggy was overcome by, or faked, hysteria in front of officers of the Continental Army’s high command.

After midnight on September 22, 1781, Arnold and John André met near Haverstraw, New York to discuss the final points of the plan to turn over West Point. The next day, André was forced to return to New York City on land and was captured by American militiamen near Tarrytown, New York. Searching André, the American militiamen discovered documents related to West Point in Arnold’s handwriting in his sock. André was taken to American lines and tried and hanged as a spy on October 2, 1781.

On September 25, 1781, word reached Arnold at his headquarters at West Point that André had been captured. George Washington was on his way to inspect the post’s defenses, therefore, if he did not know yet that Arnold was a turncoat, he certainly would soon enough. Before Washington arrived, Arnold escaped along the Hudson River to British lines.

Peggy was left behind and met Washington and those accompanying him in hysterics. It has been long debated if this was a genuine outburst of hysteria for Peggy, or if she was putting on a show to shield her own involvement in the plot. Peggy was calmed down multiple times by the American officers, before she would begin her hysteria again. Pointing to the ceiling at one point, she cried, “the spirits have carried [Arnold] up there, they have put hot irons in his head!” Then the hot iron went from Arnold’s head to her own and only Washington could remove it. With this, the General was brought in to see her and she accused him of being an imposter. Peggy’s frenzy continued into the early evening when finally she regained control of herself and but still felt the despair of what had happened that day. If this was all a ploy, she had forced Washington, Lafayette, Alexander Hamilton, and countless to fall hook, line, and sinker for it.

Fact #10: Although there is no hard evidence that Peggy was directly involved in Arnold’s plot, there is plenty of circumstantial evidence.

There are many coincidences in the story of Peggy Shippen and Benedict Arnold that seem to directly link her to the plot. In 1782, Peggy was gifted an annual pension of £500 by King George III, “obtained for her services, which were very meritorious.” One can only wonder what these “meritorious services” were if they were not direct involvement in the conspiracy. Another interesting story involves Theodosia Prevost, the wife of Aaron Burr. Following the reveal of Arnold’s treason, Peggy was allowed to return to Philadelphia temporarily before being forced to leave. On the way from West Point, she stopped to visit the Burrs in Paramus, New Jersey. It was here that she opened up about what had happened and gleefully confessed about being part of the plot.