African Americans at Antietam

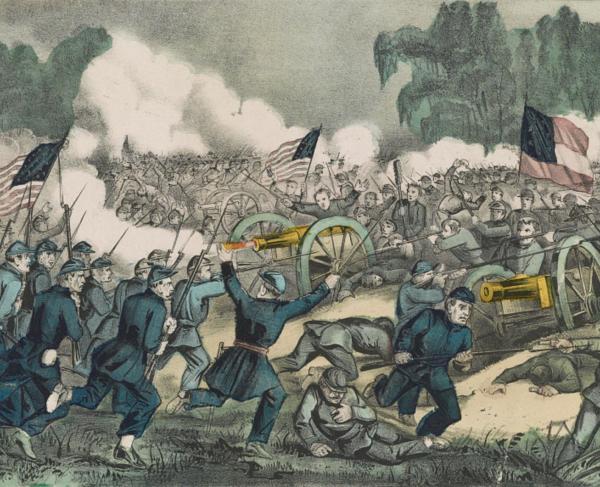

To the citizens of Sharpsburg and Washington County, Maryland, slavery was not a foreign concept. In fact, these people witnessed firsthand the divisive and oppressive nature of the institution. While Maryland was a divided state when it came to the issue of slavery and secession, Washington County was overwhelmingly pro-Union. About 139 men enlisted in the Union Army from the Sharpsburg area, including eight men who fought for the United States Colored Troops (USCT). In contrast, only 14 Washington County men fought for the Confederacy. However, Sharpsburg and the surrounding areas remained a microcosm of the nation’s complicated relationship between the war and slavery.

Despite holding pro-Union sympathies, Sharpsburg was by no means free. Washington County listed 1,435 people as enslaved and 398 as slaveowners in the 1860 census. Though the German farmers near Sharpsburg were less likely to own slaves than the planters of the Deep South, slavery still dwelt among the small homes and farms throughout Western Maryland. Its proximity to Shepherdstown, Virginia (now West Virginia), a pro-Confederate and pro-slavery town, also allowed slavery to thrive in the area.

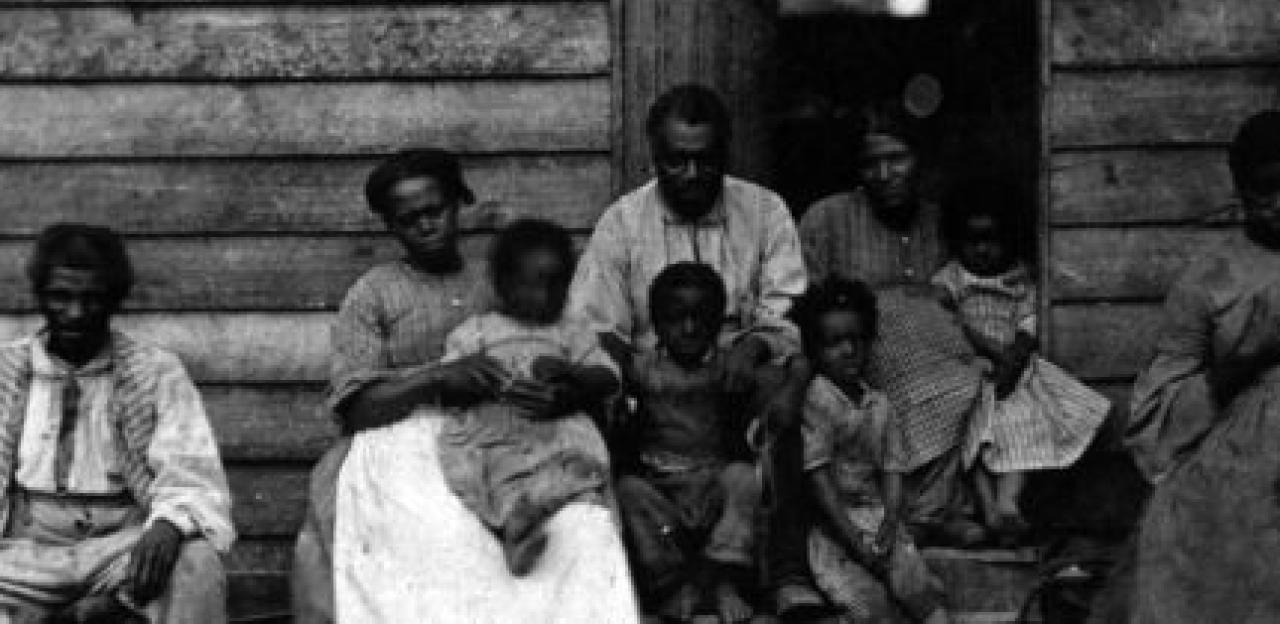

Families who lived on what became the Antietam battlefield harbored very different beliefs about Union and slavery. Henry Piper, whose farm witnessed heavy fighting near the Sunken Road, fashioned himself a Unionist but owned several slaves at the time of the battle. Dr. Augustin Biggs, a respected Sharpsburg physician and “strong Union man," owned three slaves in 1860. Samuel and Elizabeth Mumma, members of the pacifist German Baptist Brethren or “Dunkers,” owned two slaves in 1862, despite their church’s staunch anti-slavery stance. However, Samuel Mumma freed one of his slaves, Lucy, when she was 28 years old, and it is possible that he had a similar intention when he purchased 11-year-old Lloyd Wilson, as Dunkers were known to do such things in accordance with their anti-slavery principles.

Some slave owners in Maryland employed methods of gradual emancipation for their slaves, while others treated their slaves as indentured servants and allowed them to work for a wage after a certain period of time. This was often a slow process, with pay split between owner and the enslaved person. Nancy Campbell’s owner freed her in 1859, after which the former slave found employment with the Roulette family on the Antietam battlefield where she worked until her death in 1892.

Regardless, slavery in Western Maryland was arguably just as brutal as in the Deep South. Families were separated and sold, while others sought a different life by escaping to freedom via the Underground Railroad. Slaves in Sharpsburg were subjected to the same system of punishment as slaves throughout the south. Abolitionism, likewise, was not a particularly popular idea in the valley of Antietam Creek and its surrounding regions. A Frederick woman remarked before the war that she earned the reputation of being one of only three abolitionists in that town. A Washington County history described abolitionists as having been thought to be “the most despicable of persons.”

When the war began in 1861, thousands of escaping slaves passed through Maryland in search of refuge with the Federal armies. In fact, a band of these refugees first passed through Sharpsburg in the Winter of 1861-1862 in search of the 13th Massachusetts Infantry in Williamsport, Maryland. About two thousand more newly freed Blacks arrived in Sharpsburg that spring. However, these refugees were met with the threat returning to slavery. The Washington County sheriff vowed to arrest any alleged runaway slaves and invited their owners to come retrieve them.

With the threat of Confederate invasion in September of 1862, the majority of Sharpsburg, including its Black residents, braced themselves. Sharpsburg once again witnessed an exodus of African Americans who fled northward through Washington County to seek safety north of the Mason Dixon Line, fearful of being captured and returned to slavery by the advancing Confederate Army. As both armies maneuvered through the Maryland countryside, the Confederates arrived in Sharpsburg first. As they did so, the town’s Black residents noticed the sickly and starving appearance of the Confederate soldiers. Christina Watson, enslaved at Delaney’s Tavern in Sharpsburg, spent the day preceding the battle of Antietam making food for the hungry soldiers. She was visited that evening by her husband, Hilary Watson, who was enslaved on the Otto farm just outside of town. They assured each other of their safety and exchanged stories about the ragged invaders.

The choice to flee their homes or stay behind to witness the battle was not left up to the enslaved men and women of Sharpsburg but rather their owners. While the Otto family fled, they ordered Hilary Watson to remain and watch over their farm. At one point, he encountered a young Confederate soldier who had broken into the Otto house and raided their pantry. As Watson remembered, the soldier was more afraid of him than he was of the soldier, and the young Rebel left after Watson threatened to “throw him down on the steps.” Later that night Watson and William Henley, a slave owned by Confederate General Robert Toombs, worked together in the Otto kitchen to prepare a meal for the officer.

The following day, Watson stood in the Otto house as shells began to fly over the farm and the battle commenced. As the fighting inched closer and closer, Watson took “one of the horses and led some of the others and went off across the Potomac to the place of a man” who was a friend of John Otto’s. There he stayed the rest of the day and listened to the sound of the battle. As shells fell over the town of Sharpsburg, Christina Watson sheltered with her fellow residents, slaves and enslavers alike, in the cellar of the tavern awaiting the outcome of battle.

Fourteen-year-old Georgeann Rollins, a free Black servant on the Phillip Pry farm, watched as couriers galloped to and from the farmhouse which served as Union General George B. McClellan’s headquarters. As the farm bustled with army personnel, Rollins also witnessed the first wounded to trickle into the hastily established hospital there. After McClellan secured an ambulance to evacuate Elizabeth Pry and her children, it is unknown whether Rollins left with Elizabeth or remained behind with Phillip.

At the Rohrback farm, eleven-year-old slave Mary Taylor sheltered with the rest of the household, including her enslaved mother, in the cellar of the brick farmhouse. Taylor was tasked with watching over four-year-old Martha Ada Mumma, the Rohrbacks’ granddaughter. From the cellar, Taylor could hear as Union General Ambrose Burnside, and his staff galloped onto the farm and conversed with Henry Rohrback. Burnside encouraged Rohrback to evacuate his family for fear that the farm may be burned. As the family scrambled to pack up, Taylor realized little Ada had wandered off. Thinking the soldiers carried her away, Taylor finally located the little girl and scolded her for running off. As the white Rohrback family evacuated north to Boonsboro, the enslaved men and women of the household, including Taylor, likely remained behind with Henry Rohrback, according to the memory of Martha Ada Mumma. As was the case with most slaves during the battle, the Taylors were probably not offered the option to evacuate with the white women and children.

When Confederates arrived in Sharpsburg, they seized Henry Piper’s farm, where on September 14, Generals James Longstreet and D.H. Hill made their headquarters. The Pipers’ slave, Caroline Summers, likely cooked for these two officers that Sunday as they made preparations for the coming engagement. Encouraged by Confederate soldiers to flee, the Piper family left for Shepherdstown on September 16, 1862. When they returned, they found their clothing stolen, livestock killed, and canned vegetables taken by Union soldiers. The soldiers had also taken along with them fifteen-year-old Jeremiah Cornelius “Jerry” Summers, Caroline’s son and fellow slave of the Piper family. Henry traveled to Frederick, Maryland, to obtain his release, which he did successfully.

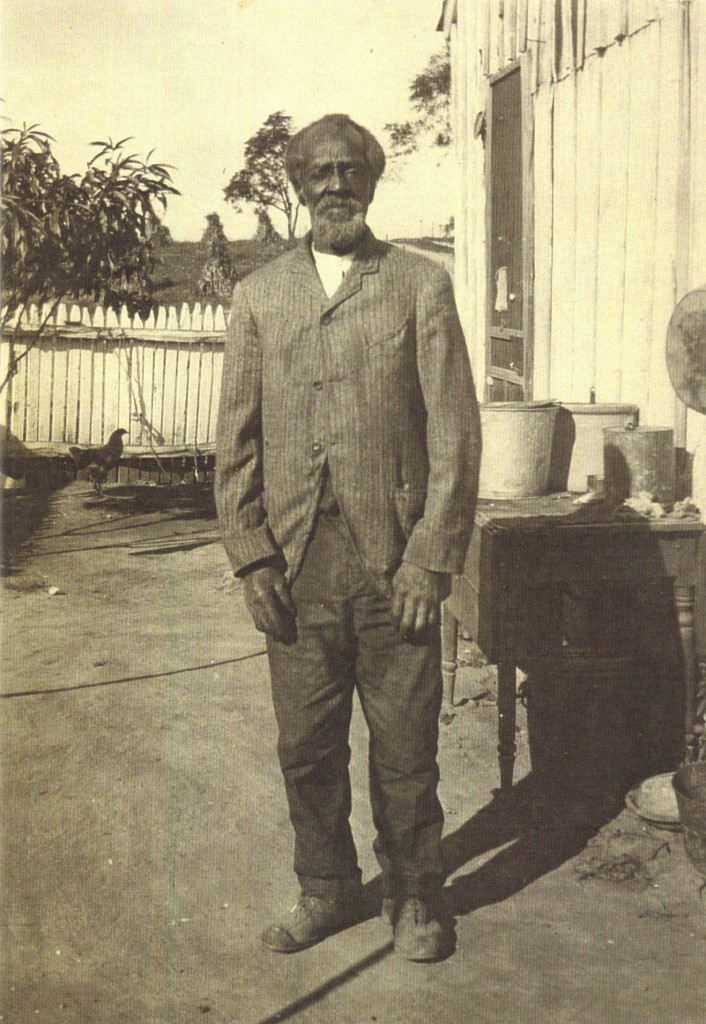

Following the Battle of Antietam, the subsequent Emancipation Proclamation did not grant freedom to Maryland’s slaves like it did those in the rebellious states. However, it allowed Blacks to enlist or be drafted into the United States Army. In April 1864, Union officers recruited Summers and enlisted him in the United States Colored Troops. Because his master was a loyal Unionist and he was only sixteen, Summers was once again retrieved by Henry Piper. When the new Maryland Constitution granted Summers freedom later that year, he continued to live with the Pipers and work for them, this time for a wage. After the war, Jerry testified on Henry Piper’s behalf when the family sued the Federal government for wartime damages. The Pipers also granted Jerry Summers and his wife Susan the use of a cottage and garden plot on the farm for the rest of their lives. Summers died in 1925 at the age of 76 or 77.

In Sharpsburg, eight Black men enlisted in the Union Army following the Emancipation Proclamation, five of whom were enslaved when they enlisted. One of these men was William Snowden, enslaved by Samuel I. Piper, Henry Piper’s brother. He enlisted in Company K of the 39th United States Colored Infantry in March of 1864 and was wounded at the battle of the Crater in July of that year. He received treatment at the General Hospital in City Point, Virginia through October and was mustered out in December of 1865. Samuel Piper received a certificate of Snowden’s enlistment which allowed Piper to collect compensation from the Federal government as a result of Snowden’s service. Despite this, service in the Union Army granted freedom to at least five of Sharpsburg’s slaves and thousands more across the nation.

Much like the nation, the Antietam Valley harbored a complicated legacy when it comes to Black Americans and the institution of slavery. Though primarily Unionist, Washington County's white population continued to advance slavery by their support of the institution, a concept perhaps perplexing to modern students of the war but equally indicative of the conflict’s complicated nature. However, Sharpsburg's Black community witnessed a major step towards freedom and equality through the Emancipation Proclamation, brought by the battle fought near their homes.

Further Reading:

- Black Antietam: African Americans and the Civil War in Sharpsburg

By: Emilie Amt. - Islands of Mercy: Hospitals in the Maryland Campaign By: Gordon Dammann and John W. Schildt.

- Too Afraid to Cry: Maryland Civilians in the Antietam Campaign By: Kathleen A. Ernst

- Shepherdstown in the Civil War: One Vast Confederate Hospital By: Kevin R. Pawlak. .

- “Slavery and Emancipation in Sharpsburg.” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Accessed July 14, 2022. https://www.nps.gov/anti/learn/historyculture/slavery-and-emancipation-….

Related Battles

12,401

10,316