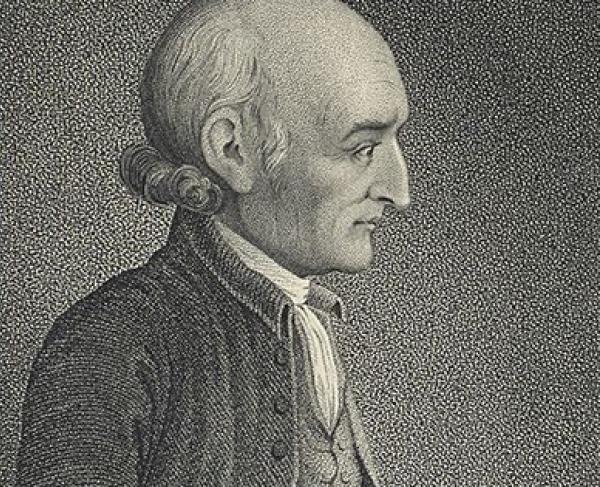

Daniel Shays

Most famous for leading the rebellion which bears his name, Daniel Shays began his life as the son of Irish immigrants, Patrick and Margaret. His parents settled in Hopkinton, Massachusetts in the 1730s and gave birth to Daniel in 1747, the second of six children. As a young man, Shays hired himself out to work as a laborer on various farms throughout the colony. He also harbored a deep interest in military affairs and drilled with the local militia whenever he could. In 1772, he married Abigail Gilbert and settled on his own farm in Shutesbury, Massachusetts, where the couple had six children together.

Shays continued to serve in the militia in the years prior to the American Revolution and eventually rose to the rank of sergeant. Following the Battles of Lexington and Concord, he and his unit marched to Boston where they took part in the growing siege. After the Battle of Bunker Hill, Shays was promoted to second lieutenant for his bravery during the fight. In 1776, he briefly enlisted in the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, also known as Varnum’s Regiment, where he participated in the New York and New Jersey campaigns.

Later that year, Shays left the army to perform recruitment duties but quickly returned to in 1777, this time as a captain in the 5th Massachusetts Regiment. He fought in the Battle of Saratoga and other engagements in New York, including the Battle of Stony Point in 1779. The following year General George Washington personally selected Shays as a captain of the guard to oversee the imprisonment of British Major John André. On October 2, 1780, Shays watched as André was hanged for conspiring with the American traitor Benedict Arnold. Later that year, Shays resigned his commission in the Continental Army.

At the end of the war, Shays found himself in hard times like many other veterans—a result of the new government’s failure to fully compensate them for their wartime service. The former captain met a storm of criticism after selling an ornamental sword, gifted to him by the Marquis de Lafayette, to help pay off his debts. To make matters worse, the Massachusetts Legislature adopted aggressive taxation policies to help pay off the state’s war deficit. The legislature’s insistence that people pay their taxes in money rather than goods or paper currency left farmers like Daniel Shays little choice. After petitioning the legislature to no avail, a group of protestors, that included Shays, marched on Northampton, Massachusetts in August 1786 to prevent the county court from convening. Though they succeeded, Governor James Bowdoin issued a proclamation condemning the act.

After the Northampton incident, Daniel Shays began leading the organized dissent against the state government. He and fellow Continental Army veteran Luke Day devised an attempt to prevent the court from convening next in Springfield. As Shays and Day marched toward the courthouse with a force of nearly 300 men, local militia under General William Shepherd stood waiting for them. The rebels chose to demonstrate rather than seize the building—successfully persuading the judges to adjourn. However, Shepherd withdrew his men to the Springfield Armory and received reinforcements over the next several months.

On January 25, 1787, Shays and his men decided to target the armory as their next move. As the rebels neared, Shepherd ordered his men to fire a series of warning shots, killing four Shaysites and wounding twenty others. The rebel force collapsed as a result and most of the men scattered north. On the night of February 3, General Benjamin Lincoln and a force of 3,000 Massachusetts militiamen surprised the rebel camp, capturing 150 men and forcing Daniel Shays and the rest to flee. While state officials granted amnesty to most of the rebels, they convicted and sentenced to death eighteen men, including Daniel Shays. However, he was pardoned in 1788 and returned to Massachusetts from his exile in the Vermont wilderness only to face condemnation by Boston newspapers. Shays spent his final decades supported by a small pension for his five years of service in the Revolutionary War. He died almost penniless in 1825. Shays’ Rebellion served to illustrate the weakness of the Articles of Confederation to some and helped influence the ratification of the Constitution