"The Battle of New Orleans" by E. Percy Moran shows Andrew Jackson standing in front of American flag with sword raised.

New Orleans

Chalmette Plantation

Louisiana | Jan 8, 1815

The United States achieved its greatest land victory of the War of 1812 at New Orleans. The battle thwarted a British effort to gain control of a critical American port and elevated Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson to national fame.

How it ended

United States victory. The British gambled and lost on a forward attack against American forces, dug into a fortified mud and cotton bale earthworks on the east bank of the Mississippi at Chalmette Plantation. British casualties far outnumbered those of the Americans. Jackson's triumph set him on a road that ended in the White House thirteen years later.

In context

After Napoleon’s defeat in the spring of 1814, the British were free to concentrate on their war in America. With a strategic focus on coastal regions and American trade and transportation, the British army attacked and burned Washington in August 1814. Although unable to take Baltimore the following month, the British nonetheless moved ahead with a plan to attack New Orleans.

Apprised of a possible invasion on the Gulf Coast, the commander of the U.S. Seventh Military District, Andrew Jackson, left Mobile, Alabama, for New Orleans on November 22. Recently promoted to Major General in the Regular Army for his successful campaign against the Creek Indians, Jackson reached the city on December 1 and began the task of assembling an army, which eventually consisted of Tennessee and Kentucky frontiersmen, Louisiana militia, New Orleans businessmen, Free Men of Color, Choctaw Indians, smuggler Jean Lafitte and his privateers, sailors, marines, and United States troops.

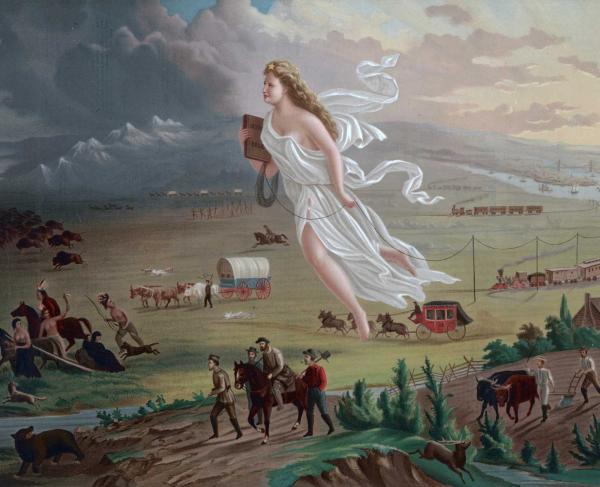

On January 8, 1815, Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson's hastily assembled army won the day against a battle-hardened and numerically superior British force. The resounding American victory at the Battle of New Orleans soon became a symbol of American democracy triumphing over the old European ideas of aristocracy and entitlement. The battle was the last major armed engagement between the United States and Britain.

British Vice Adm. Alexander Cochrane's fleet arrives near Ship Island, some 60 miles east of New Orleans, on December 8. After disposing of an American flotilla on Lake Borgne, Cochrane and the temporary army commander, Maj. Gen. John Keane, decide to ferry the British infantry through the nearby bayous and approach the city from the south. The British land below New Orleans on the morning of December 23.

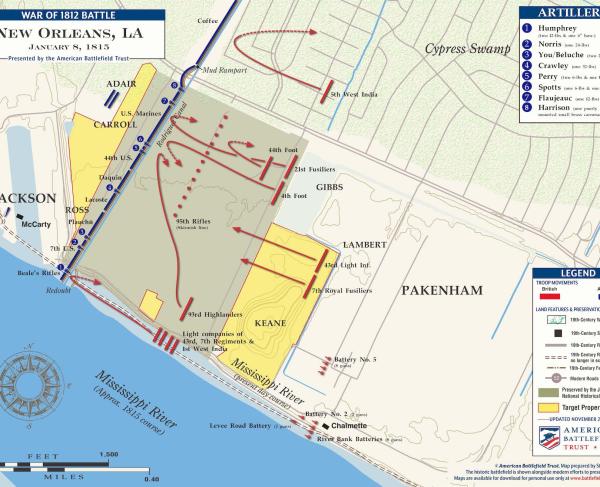

When he receives word of the landing, Jackson boldly marches out to meet the enemy. In a daring nighttime assault, the Americans strike the British camp. A sharp but inconclusive fight ensues and after several hours, Jackson disengages and withdraws two miles north to the Rodriguez Canal. The Americans immediately begin construction on an earthwork, later known as Line Jackson. It runs perpendicular from the Mississippi River for three quarters of a mile to a cypress swamp. A marine battery is established on the right bank of the river.

On Christmas Day, Gen. Sir Edward Pakenham arrives and assumes command of the British expeditionary force. Annoyed by his subordinates' inability to defeat Jackson and capture New Orleans, Pakenham moves his army to the Chalmette Plantation, about five miles southeast of New Orleans, on December 27. Over the course of the next five days, Pakenham makes two attempts to breach Line Jackson. Both are repulsed by the Americans. Left with few options and buoyed by the arrival of reinforcements, Pakenham decides to launch a major assault on the morning of January 8, 1815.

5,700

8,000

January 8. The British attack gets underway before sunrise. On the British left, Maj. Gen. John Keane's infantry penetrates an unfinished redoubt, only to be brought to a grinding halt in front of the New Orleans Rifles and the Seventh U.S. Infantry. Maj. Gen. Samuel Gibbs's column advances against the American left center where his ranks are decimated by Tennessee and Kentucky militia. Gibbs is mortally wounded in the attack.

Attempting to rally his men, Pakenham rides forward with his staff, but is hit by an American volley. He is carried from the field and later dies of his wounds. Of the 3,000 men under Gibbs and Keane, 2,000 become casualties in less than 30 minutes. A soldier from Kentucky later wrote, "When the smoke had cleared and we could obtain a fair view of the field, it looked at first glance like a sea of blood. It was not blood itself, but the red coats in which the British soldiers were dressed. The field was entirely covered in prostrate bodies."

Devastated in front of Line Jackson, the remnants of the British force withdraw to beyond range of the American guns. Despite the limited success of Col. William Thornton's attack against the marine battery on the right bank, Pakenham's successor, Maj. Gen. John Lambert, is unable to salvage the British effort and recalls Thornton's force.

62

2,034

The British do not venture another run at Line Jackson. Despite their catastrophic defeat, they continue to bombard Fort St. Philip near the mouth of the Mississippi River for another week. They finally withdraw from New Orleans on January 18.

The American victory swiftly resounds with news of the ratification of the Treaty of Ghent, which brings the War of 1812 to an end. Americans hail Jackson as a hero. The victorious battle foretells the Age of the Common Man, propels Jackson toward the presidency, and for the next half century, January 8 is marked by celebrations across the United States.

Although American and British negotiators signed a peace treaty between their two nations in Ghent on December 24, 1814, news of the treaty had not reached the shores of the United States by January 8, 1815. Neither the opposing armies nor the United States Congress were aware of the signing. So, the war continued, and the American defense of the valuable port of New Orleans remained critical.

This last major battle of the War of 1812 sealed the victory for the Americans and won the young United States international recognition. But in the end, was the battle really necessary if the treaty was already signed? Because the treaty specifically stated that fighting between the United States and Britain would stop only when both governments ratified the treaty, the battle was, indeed, justified. The Treaty of Ghent was not ratified by Congress until February 16, 1815, more than a month after the battle. Except for a few tense diplomatic incidents, the treaty ushered in two centuries of peace between the United States and Britain.

Lafitte and his brothers ran a lucrative smuggling operation in Louisiana before the War of 1812. They purchased slaves cheaply in the West Indies and sold them for a profit in New Orleans, where a federal ban on slave imports drove up the price. The Lafitte brothers also worked for Cartagena (now Colombia) to sabotage Spanish commerce. Goods they captured in the process were sold illegally in Louisiana, where they made Barataria Bay their home base. The bay, protected by islands and bayous south of New Orleans, was perfect for their smuggling operation. Lafitte’s “Baratarians” often faced capture and imprisonment by United States customs officials as well as the Spanish Navy. The water in Barataria Bay was deep enough that Lafitte could easily launch into the Caribbean but shallow enough to prohibit Spanish war ships from following him home.

During the War of 1812, the British offered to pay Lafitte handsomely for his help in fighting the Americans at New Orleans. Instead, Lafitte made a proposal to the governor of Louisiana. He would help the Americans defeat the British in exchange for a pardon from all smuggling charges against the Baratarians. The Louisiana legislature rejected Lafitte’s proposition and the privateer, without ties to either nation, was continually harassed by both armies.

Lafitte’s circumstances changed with the arrival of Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson in New Orleans in 1815. Jackson had heard that the Baratarians were the best gunners in the Caribbean and knew the terrain around New Orleans well. Jackson needed them. Although questions about the privateers’ loyalty and lawlessness gave him pause, he reconsidered Lafitte’s offer.

His gamble paid off. During the Battle of New Orleans, about 50 Baratarians manned the guns on American battleships and operated the land batteries. Jackson and Lafitte got along so well that the privateer became Jackson’s unofficial aide-de-camp. After the war, President James Madison rewarded Lafitte for his service with a full pardon, and this unlikely veteran of the Battle of New Orleans resumed his illicit career on Galveston Island in Spanish Texas.

New Orleans: Featured Resources

Related Battles

5,700

8,000

62

2,034