Pea Ridge was the first sizable battle of the Civil War to involve Indian troops, mostly because their current homeland lay only a few miles west of the battlefield. The Five Civilized Tribes, including the Cherokee, had lived in the Indian Territory, now the state of Oklahoma, ever since their removal from ancestral homelands in the southeastern states a quarter-century before the war.

The Cherokees not only were the most numerous of the Five Civilized Tribes, but they had assimilated more with white culture than the Choctaw, Creek, Chickasaw, or Seminole. They were the only Native Americans to create a written form of their language and they published a newspaper in that language. Many Cherokees adopted the white man’s dress and most began to utilize American farming methods. Cherokee lawyers brought cases defending their desire to remain in Georgia and North Carolina to the United States Supreme Court. A handful of elite Cherokees operated large plantations with African-American slave labor.

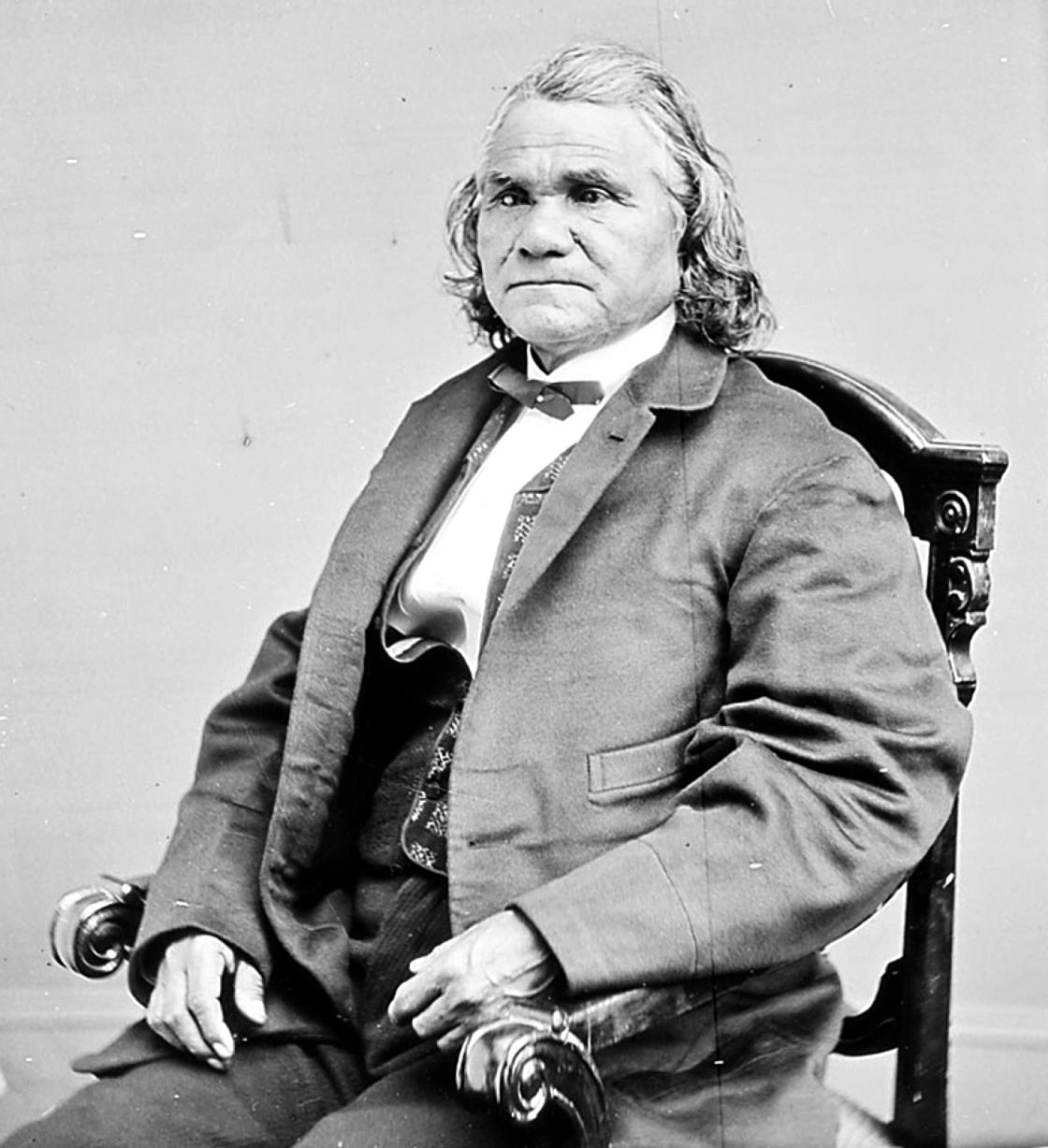

The Civil War divided the Cherokees; only a small minority remained loyal to the Union, as most Cherokees tended to favor the Confederacy. Confederate Brigadier General Albert Pike negotiated treaties between all five tribes and the government in Richmond. He authorized the creation of regiments for home defense, with treaty stipulations that these Indian soldiers were not required to leave the Territory. Seeing no alternative, the pro-Union faction among the Cherokees ultimately decided to cooperate with Pike. The Unionists organized Colonel John Drew’s 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles, while pro-Confederates organized Colonel Stand Watie’s 2nd Cherokee Mounted Rifles. With the 1st Choctaw and Chickasaw Mounted Rifles, and the 1st Creek Regiment, Pike had a sizable force of Indian troops by early 1862.

Pike was under no illusions about the quality of manpower he commanded. The Arkansas general described them as “entirely undisciplined, mounted chiefly on ponies, and armed very indifferently with common rifles and shotguns.” Yet Major General Earl Van Dorn ordered him to bring his troops into Arkansas on March 3, 1862. Pike consulted his men and found much reluctance to comply; only after he promised to issue them their back pay were they willing to cooperate.

On March 5, Pike led the 1st Cherokee Mounted Rifles and the 2nd Cherokee Mounted Rifles into Arkansas. The other two regiments were not yet ready to move. Captain Otis G. Welch’s Texas Cavalry Squadron, about 100 men, joined Pike, whose column numbered no more than 900 troops. They reached Van Dorn’s army late on March 6, in time to participate in the fighting the next day.

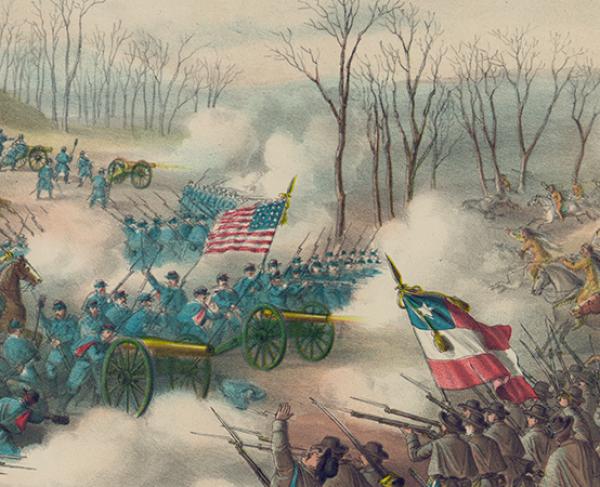

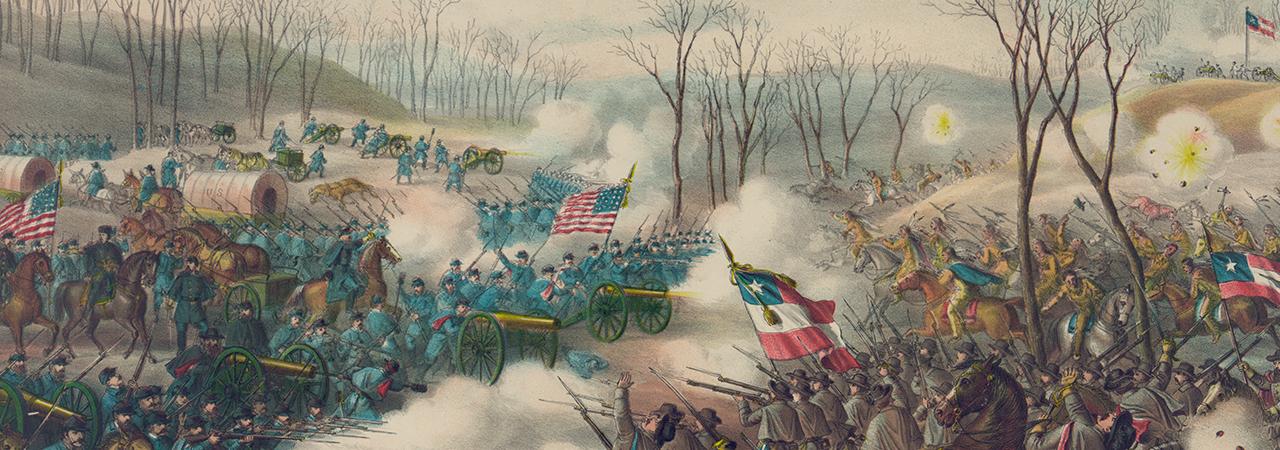

Pike’s Indians played a colorful role in taking the Union position on Foster’s Farm. He dismounted Watie’s men and sent them to lead the way. The Indians did not directly attack Captain Gustavus M. Elbert’s 1st Missouri Flying Battery. Pike instead hit a small column of two companies belonging to the 3rd Iowa Cavalry that had been led north of the Union position up Foster’s Lane by Lieutenant Colonel Henry H. Trimble. The Cherokees and Texans surprised the Iowans, seriously wounded Trimble, and sent his men fleeing as Brigadier General James M. McIntosh’s cavalry captured three of Elbert’s guns and dispersed the other Union troops on Foster’s Farm.

Then occurred the incident which made Pike and the Cherokees infamous. Confusion prevailed on Foster’s Farm as disorganized Confederates celebrated their victory around the captured guns. Pike’s Indians also wandered over to the battery site to partake in the hoopla, but only after a few of them scalped at least eight of Trimble’s cavalrymen and mutilated several others. No eyewitness left a record of this act, which took place in the woods. It is quite likely that many of the victims were still alive when they were scalped. A Confederate officer who later witnessed their celebration around the captured artillery wrote, “the Indians swarmed around the guns like bees, in great confusion, jabbering and yelling at a furious rate.” Pike himself admitted that they were “in the utmost confusion, all talking, riding this way and that, and listening to no orders from anyone.” Federal artillery fire from the southern edge of Oberson’s field onto Foster’s Farm quickly dispersed the Indians, who fled back into the woods and fired “at every one having on a blue coat, whether friend or foe,” according to a Confederate soldier. Pike managed to stop this indiscriminate firing but he had to cajole his men for nearly an hour before a few of them were willing to drag the captured cannon into the woods.

Pike was horrified when he learned of the scalpings after the battle, and issued orders to his troops to refrain from such incidents in the future. He also court-martialed a soldier for killing a wounded Federal. But the Northern press pilloried Pike and excoriated his Indian troops for their misdeed. Pike resigned his commission in the Confederate army in July, 1862, and was later indicted in Federal court for inciting war atrocities. The perpetrators of the scalpings and mutilations were never identified, but Unionists and Confederates among the Cherokee blamed each other for the incident. The Federal troops who survived Pea Ridge were also horrified at what happened. Captain Oliver Hazard Perry Scott of the 3rd Iowa Cavalry remarked, “There was two of them infernal indians taken prisoner, and we have seen one that was killed. I wish it had been the last of that race. There was quite a number of our men scalped by them, two of our company....There will be no quarter shown them after this, that is certain.”

Why did the Cherokees scalp and mutilate Union soldiers at Pea Ridge? Unfortunately, those who could best answer that question remained silent. There are no surviving accounts of the battle written by Native Americans who served in the two Cherokee regiments. Of those eight hundred men, probably fewer than a dozen actually participated in this ritualistic action. The silence surrounding the incident allowed non-Indian commentators to interpret it for their own purposes and within the context of European rather than Native American culture.

Scalping was practiced by some Native Americans before contact with Europeans. The French recorded its appearance among the Hurons in the sixteenth century. Eastern tribes such as the Creeks and Cherokees were known to have incorporated scalping into their activities, but it appears to have been most common among the Plains Indians. For all Native Americans who practiced scalping, it was important for purposes of symbolism and retribution. Taking the hair of one who had murdered a member of the family or tribe was a symbolic way of replacing the lost. The lock of hair also symbolized victory over an enemy and often was used as a decoration in celebrations. A form of mutilation itself, scalping naturally became part of a wider range of practices by some tribes that ranged from simply cutting the skin of dead enemies to castration.

Among the Cherokees, before their removal to the Indian Territory, scalping was practiced for one of two reasons. First, scalping occurred as a means of exacting revenge for the killing of Cherokees by other Native Americans. It was done with a precise sense of justice. Cherokees took only enough lives and scalps to account for the number of slain Cherokees. In this way, a general war between neighboring tribes was avoided. Second, scalping occurred at the instigation of Europeans. During the French and Indian War, the British offered scalp bounties to the Cherokees, encouraging them to attack tribes allied with the French. Many young Cherokee men were so impressed by the lure of payment that they began to collect the scalps of any tribe that was available, even friendly peoples such as the Chickasaw. This not only threatened a war with the Chickasaw but represented a threat to the social values of the Cherokee Nation. A Cherokee leader named Little Carpenter, unable to punish the scalp-takers, finally asked the British to rescind their offer of scalp bounties.

The episode at Pea Ridge obviously did not fall into the first category, scalping and mutilation as a form of revenge. Pea Ridge was the first major engagement between the Confederate Cherokees and the Union army, and there could have been no question of retaliation for a previous wrong. The episode at Pea Ridge does, however, fall directly into the second category. From the Cherokee perspective, the Civil War was a conflict between outsiders, and many of the Cherokees found themselves drawn into it only reluctantly. In the case of Pea Ridge, the two Cherokee regiments were nearly like mercenary troops coerced by politics and money into leaving the Indian Territory and fighting alongside Confederate troops for the defense of Arkansas. Those few Cherokees who took up the scalping knife were not paid bounties, but their role in Confederate service was analogous to their role as British allies a few generations earlier. John Bull and Johnny Reb both created a political-military situation that encouraged a few individuals to abuse a time-honored ritual of Cherokee culture.

Related Battles

1,384

2,500