The French Quarter of New Orleans

Located roughly one hundred miles from the mouth of the Mississippi River, New Orleans has been home to rich culture and history. Before the arrival of the Europeans, the land where New Orleans sits is home to various indigenous tribes, including the Bayougoula and the Choctaw. The local tribes named the land "Bulbancha," meaning "land of many tongues "due to its diverse population. The indigenous people used the land for its abundant ecological resources and waterways to trade amongst themselves. The indigenous tribes used Bayouk Choupique (known today as St. John's Bayou) as a port to connect with the mouth of the Mississippi River. The river and location allowed the ingenious population to build commercial relationships with other tribes.

On May 8, 1541, Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto traveled through and documented the location of the Mississippi River. Following de Soto, French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle set sail for the mouth of the Mississippi. In 1682, Salle began his expedition from French Canada down the Mississippi with the goal of setting up a trading port and a colony for France. Once reaching the mouth, La Salle and his men recognized the strategic need to control the Mississippi. With colonial holdings in Canada and the Caribbean, the Mississippi connected and produced trade amongst the French colonies. After claiming the watershed for France and naming it after King Louis XIV, France begins establishing a colony. La Salle produced a small settlement of men, women, and children within the bayous of Louisana. The colonists did not adjust to the warm and wet climate and left to return to France or back to Canada. Although La Salle's small colony ultimately failed, it had established French influence for fifteen years around the Bulbancha area.

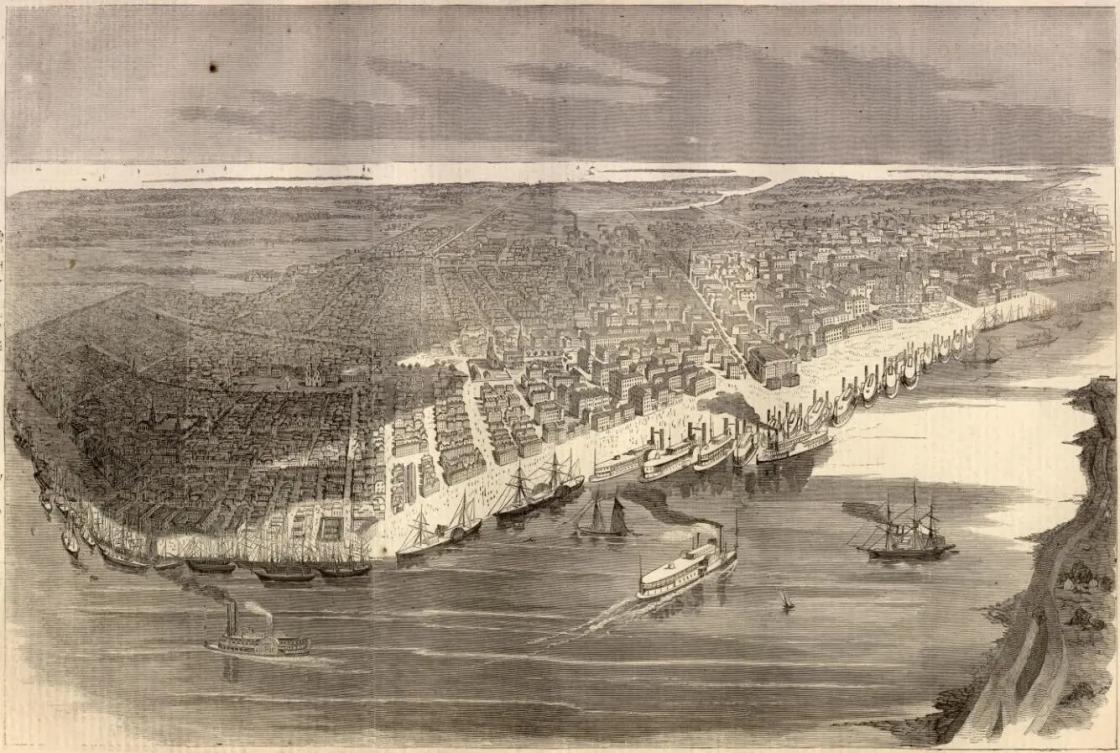

By the end of the 17th century, the French consumed parts of Louisiana with the arrival of French explorer Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville and his brother Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville. Sent by King Louis XIV, the brothers sailed for the mouth of the Mississippi to expand the French territory. Arriving in 1699, the brothers sailed up the river to find a strategic location for a new settlement. As they sailed, they noted a feast when they camped at Point du Mardi Gra. The French colonists would later begin celebrating the fest known as Mardi Gras following the founding of New Orleans in 1718. The new settlement formed in the lower Mississippi valley, and Fort Maurepas was set up to protect the new colony (present-day Ocean Springs, Mississippi). The brothers continued to explore the lower Mississippi River valley as the settlement grew. Bienville quickly learned the language of the local tribes and began diplomatic relationships with the local indigenous population. After officially setting up the colony, Iberville was called back to France, and Bienville was selected as governor of French Louisiana. He served as governor intermittently on four occasions. During his time in Louisana. As governor, he explored the waterways of the Mississippi, and in 1717, Bienville wrote to the French government about his discovery of a "beautiful crescent along the river." With French approval, he began the settlement, naming the location La Nouvelle-Orléans in 1718. The new settlement's location helped the French due to its proximity to the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain, supplying a shortcut for shipping. Within a brief time, Bienville proposed that the capital of French Louisiana be temporarily moved from Mobile to the new location of La Nouvelle-Orléans, known as New Orleans.

The settlement prospered under Bienville and continued to grow, giving him the name "The Father of Louisiana." The well-known French Quarter was constructed by working closely with cousin and French engineer Pierre le Blond de la Tour. Designed by Bienville, the quarter consisted of seventy military-style grids divided by streets. La Tour designed the streets to pay homage to Catholic Saints and French royal houses. Examples include the naming of Bourbon Street after the French House of Bourbon. Originally the quarter was constructed with wood, but the wet environment quickly decayed the buildings. After the quarter was reconstructed using bricks, it became a thriving trading port and urban center, and in 1723, New Orleans became the official capital of the French colony of Louisiana. New Orleans had become a flourishing colony under French influence, but it was ceded to the Spanish after France's loss in the French and Indian War in 1763.

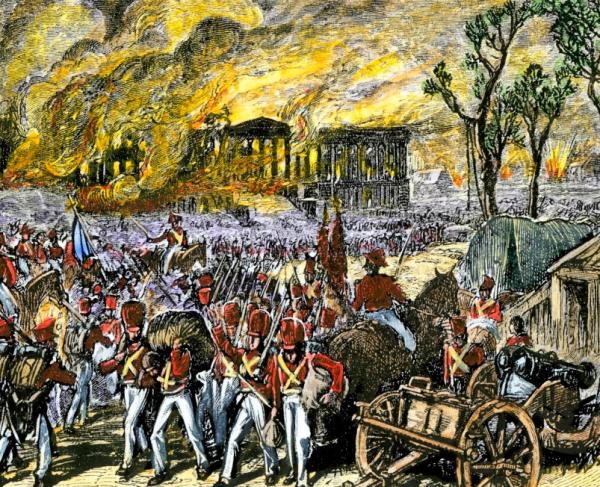

France ceded New Orleans to Spain in the Treaty of Fontainebleau to prevent the colony from falling under British rule. The French colonists did not take kindly to being under Spanish control. The new Spanish government had to accommodate the ethnically diverse population of New Orleans. With most colonists originating from France or Spain, the capitol was also home to Native Americans, Creole, Cajuns, and Africans, both enslaved and free. The colonists were flexible with Spanish officials until the appointment of Spanish colonial governor Don Antonio de Ulloa. Ulloa arrived with a small detachment of Spanish troops in the port of New Orleans in March of 1766. While in office, Ulloa approved unpopular financial decisions, including restricting trade with Great Britain and banning the importation of French wine. Angry colonists called on Charles III, the King of Spain, to remove Ulloa from his position. When the king failed to remove Ulloa, the Creole population incited a rebellion to force the Spanish governor out of Louisiana. Attorney General Nicolas Chauvin de La Frénière led the Louisiana Rebellion of 1768. In October of 1768, the uprising began and successfully sent Ulloa back to Spain. The French colonist's celebrations were cut short with the arrival of 2,000 troops and 24 ships under the command of General Alexandre (Alejandro) O'Reilly. On August 18, 1769, O'Reilly officially ended the rebellion and took possession of New Orleans and Louisiana. The rebellion's leaders were executed, and supporters were jailed, officially ending the uprising. O'Reilly became the new governor of Louisana and enforced restrictive laws as punishment for the rebellion.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Spanish crown retroceded Louisiana back to France under the reign of Napoleon. United States President Thomas Jefferson began negotiations with France on the purchase of the Louisiana territory. The United States wanted to buy the territory to gain access to the Mississippi River and the port of New Orleans. Future president James Monroe and Robert Livingston, the United States minister to France, were sent to negotiate with Napoleon and the French government on the price of Louisiana. When Monroe arrived in Paris in 1803, Livingston informed him that France would sell the entire territory for a set price. On April 30, an agreement was reached that the United States would buy 827,000 square miles (about twice the area of Egypt), including New Orleans, for 15 million dollars. The purchase announcement was made on July 4, 1803, in Washington, D.C. The Senate ratified the Louisiana Purchase Treaty on October 20, and New Orleans and Louisiana territory officially joined the United States on December 30, 1803.

Related Battles

62

2,034