Foreign Policy in the Early Republic

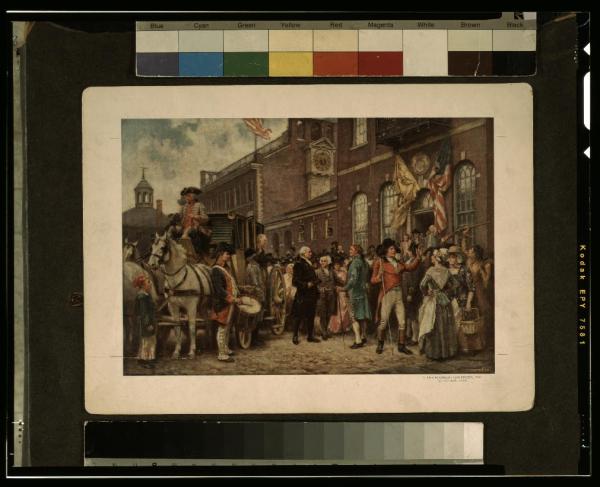

Washington's Cabinet

With independence granted to the United States through the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the nation took its place among the rest of the global political bodies. Like its domestic policy, the foreign policy of the early American Republic was often laden with crisis after crisis. As political parties emerged over differing interpretations of the Constitution and the meaning of the American Revolution, lines were drawn, and both sides had entrenched attitudes on their views. The Federalists, led by Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, favored stronger relations with England. However, the Democratic-Republicans, led by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, preferred alliances and stronger relations with France.

Britain and France's constant warring in this period squeezed the new nation, adding to the difficulties. Entanglement in European affairs proved to be a tightrope for the administration of the first president, George Washington, and the several presidents who followed. These foreign policy difficulties lingered until 1815, ending with closure of the War of 1812.

While the United States had broken its shackles from Great Britain, the new nation held much in common with her former mother country including language, customs, culture, and a mercantile economy. By the 1790s, England was the major trading nation with the United States. Hamilton’s vision for America consisted of a great mercantile nation, which had banks and commerce standing at the forefront of American achievements.

Jefferson’s undying admiration for France opposed Hamilton's vision. As a minister to France in the 1780s, he fell in love with French culture and reminded everyone how France had saved the American Revolution by signing a formal treaty of alliance and supplying much needed weapons and men. He strongly believed that the United States had an obligation to repay France for their help during the American Revolution.

Beginning in 1789, the French Revolution complicated foreign policy matters. Some, like Jefferson, saw it as a natural outgrowth of the American Revolution and putting to an end to monarchy. But as the French Revolution devolved into chaos, ruthless murder, and terror, others including Washington and his Vice-President John Adams saw things differently. In 1792, the French monarchy collapsed, and Revolutionary France declared war on England. The United States could not avoid the vice grip both warring nations held on the new nation and on the high seas. Washington’s cabinet drew their verbal battle lines. Hamilton clearly backed England in the conflict, and Jefferson favored France.

In early April 1793, the French dispatched Edmond-Charles Genet as Minister to the United States with the goal of obtaining American support for France in its war against England and defending French colonies in the Caribbean. Genet’s schemes became a diplomatic embarrassment. Though a skilled diplomat, Genet pushed to secure a commercial treaty between the United States and France and an American adherence to the Treaty of Alliance of 1778, particularly with an eye toward getting permission for the French Navy to use American ports as bases for their privateer operations in the Atlantic. Genet fancied himself as “Citizen” Genet as a tip to his pro-revolutionary leanings. Even though he was initially rebuffed by Secretary of States Jefferson, he continued to seek the outfitting of French privateers in American ports. This proved highly problematic for the Washington Administration.

On April 22, 1793, at Alexander Hamilton's urging, Washington signed the Proclamation of Neutrality in the war between England and France. Angered and humiliated, Jefferson resigned as Secretary of State. This also complicated matters for Genet who refused to respect the United State's request to not outfit French privateers in American ports. The Americans asked France to recall Genet, but considering the instability in revolutionary France, Genet decided to settle in the United States.

Upon leaving office, Jefferson utilized Philip Freneau, the editor of the Jeffersonian newspaper, The National Gazette, to viciously attack the Washington administration and its policies. Additionally, in a letter to the Italian agriculturalist and philosopher, Philp Mazzei, Jefferson wrote, "Men who were Sampson’s in the field and Solomon in the Councils have had their head shorn by the harlot of England.” He specifically attacked George Washington, and when this letter was leaked, Washington broke all communications with Jefferson. The political battle became increasingly personal.

In late 1794, Washington signed the Jay Treaty with Great Britain, mostly to resolve loose ends from the Revolutionary War. The treaty angered France who saw it as a violation of the Neutrality Act and an act of ingratitude toward the nation that had helped the United States win independence. The treaty led to a collision course on the Atlantic, as France began to seize American merchant ships for five years.

In 1796, an exhausted George Washington chose not to seek a third term as President. He longed for his “vine and fig tree” on his Virginia estate, Mount Vernon. Before leaving office, Washington delivered his Farewell Address which appeared in the Daily American. Among many things Washington urged the United States to stay out of European affairs. For the next 100 years, Americans mostly pursued Washington’s desires until war broke out with Spain in 1898.

John Adams was elected in 1796. Though he only served one term as President, it proved to be tumultuous. While he took the Oath of Office in March 1797, tensions remained high with France. His highest priority was to restore amicable relations with the French. In the aftermath of his inauguration, Adams sent three American diplomats on a mission to Paris to negotiate peace. They were directed to meet with French Foreign Minister Charles de Talleyrand, who rebuffed the diplomats and sent three French agents to meet them. These French agents told the Americans that the United States would have to pay a significant bribe and agree to loan France an exorbitant amount of money before they would meet Talleyrand in person. Furious, the American diplomats returned home and reported to Adams. When word got out about the diplomats' treatment, American anger boiled over and some people even called for war with France. The slogan, “Millions for defense. Not one cent for tribute” echoed across America. When Congress asked for a report, Adams simply changed the agents’ names in the diplomatic papers to X, Y, and Z, thus giving name to the XYZ Affair. In the heated atmosphere, Adams secured military appropriations for the building of an American naval fleet. In July 1798, Congress approved military action against France, without a declaration of war. The Quasi-War lasted for two years with America’s navy besting the French Navy at sea on several occasions. By 1800, feelings had cooled, and the Quasi-War came to an end. Adams lost the Election of 1800 to Jefferson, shortly before word reached the United States that hostilities between France and the United States had ceased.

Despite successful United States naval operations against the French, English warships continued to prey on American merchant vessels. The American struggle to maintain open and free sea lanes would create conflict for another 15 years.

In 1807, after years of frustrating problems with the English and the French, President Jefferson made a fateful and extreme decision in an effort to avoid war. He championed the Embargo Act of 1807, which shut down all international commerce in the United States. Ports like Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Charleston were closed. Merchant vessels were not permitted to leave or to enter. With no commerce in the harbors, the United States sank into its first genuine economic crisis. Political cartoons and newspaper editorials mocked Jefferson and his policy. Merchants, located mostly in the North, seethed as their businesses struggled or failed. Jefferson managed to ride out the storm in his remaining months in office, choosing to follow Washington’s lead and depart after two terms in office. His successor, James Madison, inherited the mess. Madison decided to let the Embargo Act run its course and opted not to renew it, but this once again put American merchant vessels at the mercy of England’s Royal Navy.

English warships began seizing American merchant vessels on the high seas, not extracting trade goods but rather forcing American merchant sailors into the Royal Navy. Life in the Royal Navy was difficult for the average sailor, and captains often practiced draconian measures to keep control of their crews. The British argued that many Royal Navy sailors jumped ship, opting to serve on American merchant ships rather than face oppressive conditions in the Royal Navy. British warships stopped unarmed American merchant vessel’s, board them, and forcibly remove sailors in a process called "impressment."

In addition to intimidation on the high seas, British agents in Canada continued to agitate American Indian tribes on the western frontier to attack settlements. A faction of new and younger congressmen, called War Hawks, were elected to Congress. These War Hawks, led by Henry Clay of Kentucky and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, pressured Madison to declare war against Britain. In 1812, Madison reluctantly asked Congress for a Declaration of War. The United States Army was ill prepared for war and engaged in an invasion of Canada, only to be turned back. On the high seas, the American Navy repeatedly defeating large British warships. During the Chesapeake Campaign of 1814, the British burned Washington, DC—a humiliating defeat for Madison and the American army. The stalwart defense of Fort McHenry in September 1814, followed by a stunning British defeat at New Orleans in January 1815, were bright spots in an otherwise dismal American foray into war. Ironically, the Battle of New Orleans was fought two weeks after American and British negotiators had hammered out a treaty at Ghent, Belgium.

When Congress ratified the Treaty of Ghent and President Madison signed it, not much had changed. In fact, the treaty used the language “status quo antebellum.” However, a new found sense of American nationalism and pride emerged from the War of 1812. Americans celebrated and claimed they had bested, within two generations, the greatest military power on earth. Following his victory at New Orleans, Andrew Jackson was proclaimed a hero and started on the road to the Presidency. The conflict also laid the groundwork for the international border between the United States and Canada, which to this day remains the longest undefended border between nations in the world.

The War of 1812 ended the intense foray of American foreign policy during the era of the new republic. In the coming decades, the nation set its eyes to the West, expanding into the interior and looking forward rather than back across the Atlantic to its European antecedents for its future.