The Cost of War

Standard medicines used during the Civil War on display at the Museum of Civil War Medicine, Frederick, Md.

The Civil War was America’s bloodiest conflict – its 620,000 dead were not equaled by the combined toll of other American conflicts until the war in Vietnam. In fact, almost as many men died in Civil War captivity as were killed in the whole of the Vietnam War. Two percent of the American population perished in the line of duty, the equivalent of six million people dying in the ranks today. The broader casualty figure for the conflict, which also includes wounded and captured, is approximately 1.5 million souls.

Figures are less certain for the American Revolution because recordkeeping was less precise. An estimated 6,800 Americans were killed in action, 6,100 were wounded and upwards of 20,000 taken prisoner. Historians believe that at least an additional 17,000 deaths were the result of disease, including about 8,000–12,000 who died while prisoners of war. Total casualties for British regulars fighting in the Revolutionary War — battlefield deaths and injuries, deaths from disease, men taken prisoner and those who remained missing – were around 24,000. Additionally, approximately 1,200 Hessian soldiers were killed and 6,354 died of disease – plus another 5,500 who deserted and settled in America after the conflict.

How to Tally the Dead

The traditional figure for lives lost in the line of duty during the Civil War comes from an exhaustive 1889 analysis of U.S. Army documents and pension records performed by Union veterans William F. Fox and Thomas Leonard Livermore, although this number is imperfect. As there are fewer records documenting Confederate mortality rates, Fox and Livermore made assumptions based on Union equivalents. A more recent piece of scholarship used modern demographic and statistical analysis of census data to extrapolate that the country’s population in 1870 was approximately 750,000 lower than would otherwise be expected. But this is a separate type of calculation than true losses to combat troops.

A Medical Revolution

The Continental army’s Hospital Department was established following the Battle of Bunker Hill in July 1775, but even the corps it established was far from professional by today’s standards. Only about 10 percent of the 1,400 medical practitioners who served had formal degrees, the rest having learned their craft through apprenticeship, as was common at the time since the new nation had only two medical schools. The most valuable reference in their arsenal was Plain Concise Practical Remarks on the Treatment of Wounds and Fractures, written by John Jones who had gone to Europe after his American apprenticeship to earn a medical degree from the University of Reims in 1751. This “Father of American Surgery” served in the French and Indian War before becoming the first professor of surgery in the colonies. Postwar, veterans of the Hospital Department went on to found a number of other medical colleges.

What is Wounded?

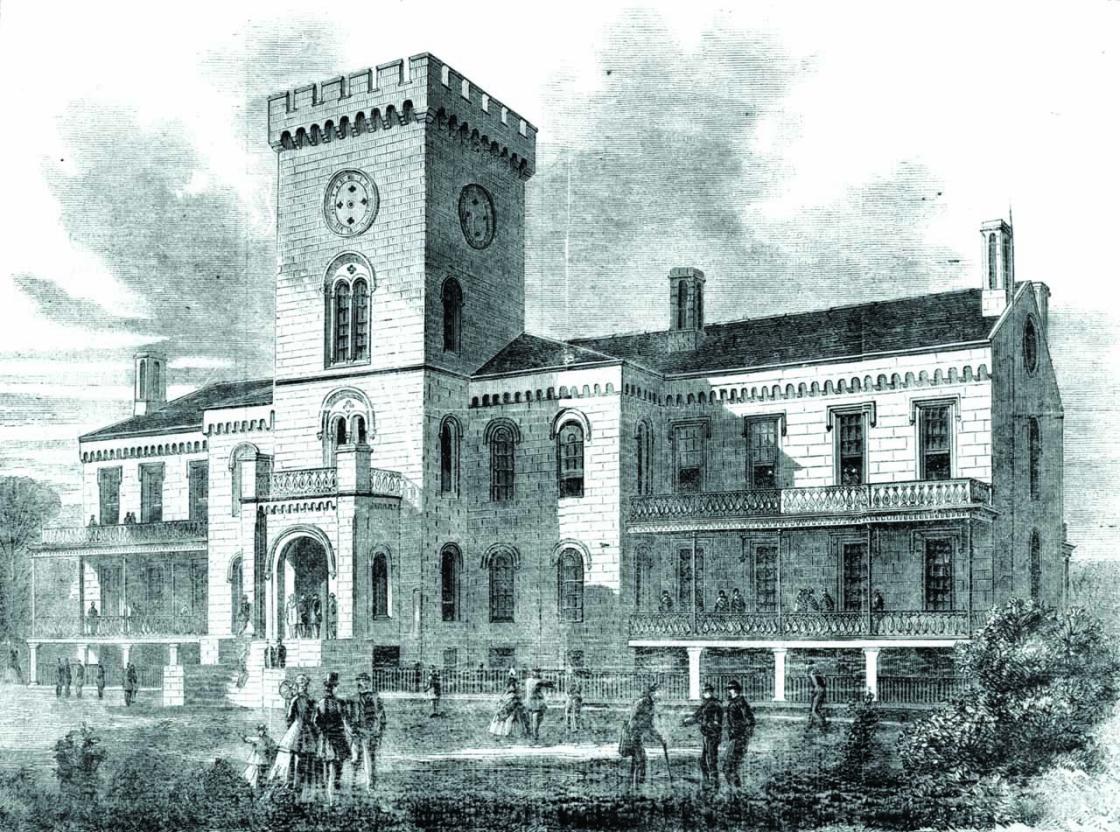

Nearly 476,000 men were reported wounded during the Civil War. Injuries ranged in severity from broken bones and flesh wounds to brain damage, lost eyesight and lost limbs. The catalog of injuries was so vast, the U.S. Army established the Army Medical Museum in 1862 as a center for research in military medicine and surgery. U.S. Army Surgeon General William Hammond directed medical officers in the field to collect “specimens of morbid anatomy ... together with projectiles and foreign bodies removed,” and to forward them to the newly founded museum for study. During and after the war, the museum staff took pictures of wounded soldiers to document the effects of gunshot wounds, as well as the results of amputations and other surgical procedures. The information was compiled into The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, published in six volumes starting in 1870.

Loss of Limb, Not Life

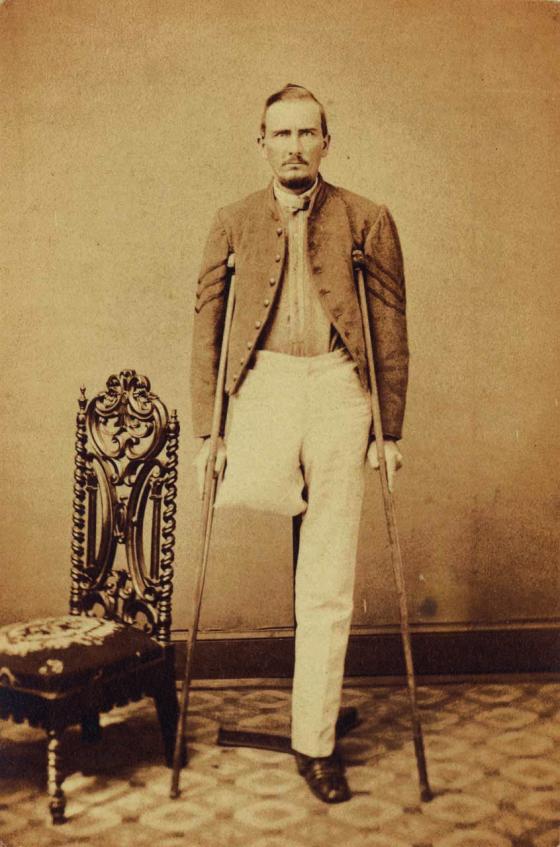

Out of 174,206 known wounds of the extremities treated by Union surgeons, nearly 30,000 wounded soldiers had amputations, with an approximate 27 percent fatality rate. Historians estimate that there were some 25,000 Confederate amputations with a similar fatality rate. When damage was less severe and limited to muscle and bone rather than nerves and arteries, resection, alternately called excision, which removed just a section of bone or mangled joint, might be a viable alternative. The shortened limb was weaker, making it more practical for arms than legs, but retained some function. Far less common than amputation, the procedure also had a higher mortality rate.

Overall, about 12 percent of battle injuries resulted in amputation, about one third of which proved fatal. However, some surgeries were more successful than others; more complicated amputations of the leg above the knee had a 54 percent mortality rate.

Invisible Injury

Not all wounds could be documented with the period’s understanding. Today, post-traumatic stress disorder is recognized as a consequence of warfare, but in the 18th and 19th centuries it was often unacknowledged and had no uniform moniker to identify its crippling symptoms. Critical examination of period records yields thousands of examples, such as Owen Flaherty of the 125th Indiana who clearly suffered from its scourge.

Before the battle of Stones River, Flaherty was described as a quiet, easygoing and well-liked man. Although he survived the war and returned home, thereafter Flaherty had trouble concentrating, sleeping and controlling his moods to the point that he became unemployable, unpredictable and volatile. Eleven years after the war ended, he was sent to the Indiana Hospital for the Insane and diagnosed with “acute mania.” But the facility made no provision for keeping or treating “chronic cases,” and Flaherty was remanded to the poorhouse, where a medical examining board noted his predisposition toward irrational anger and violence, as well as a delusional “fear from imaginary persons who intend to kill him.” They attributed his condition to “some mental shock probably sustained in the service.”

Opioid Epidemic

In the Civil War’s wake, thousands of veterans became addicted to morphine and opium, medicines used extensively at the time to treat everything from painful injuries to lingering sicknesses, even diarrhea, during the war. Veterans dubbed their dependency “opium slavery” and “morphine mania,” among other names.

Their plight was highly stigmatized, with many Americans viewing veterans who suffered as immoral and unmanly; they deserved to be punished, not helped, and so struggled to find sympathy or medical care. They often died of accidental drug overdoses or suffered alive in the grips of agonizing addiction. Ongoing usage was facilitated by ease of access as the hypodermic syringe became widely available and with the Sears and Roebuck Catalog selling heroin by mail order. Modern historians have categorized the situation in the 1880s as our nation’s first opioid epidemic, a problem that persists to this day.

Not Biting the Bullet

During the Revolutionary War, pain relief for major surgery like amputation was far from universally available, but might involve the administration of rum, wine or a tobacco juice mixture. Instead, patients were held down by multiple surgical attendants, although a new French screw-type tourniquet might be available to control bleeding.

Anesthesia was developed in the mid-1840s, and by the Civil War chloroform was fairly common for surgeries, administered through inhalation. Contrary to popular belief, 95 percent of surgeries had some level of anesthesia administered, and there are no contemporary accounts of bullets being given for patients to bite down on. Patient movement or moaning, even when an individual was unconscious, seen by outside observers was likely a side effect of the dosages administered.