The medical profession is a highly specialized field where students dedicate years in schooling and training to become certified by a medical board. Today patients travel to doctors’ offices for treatments and tests, go to pharmacies for medicine, and more. However, the field of medicine was not always so knowledgeable and professional, and many of these changes occurred throughout the nineteenth century.

At the beginning of the 1800s, the medical field was a male-dominated field where not all doctors were professionally trained. Many doctors in rural areas went through apprenticeships instead of attending medical school. Most of the time, doctors traveled to patients’ homes to administer care and dispense medicine that was mainly herbal or chemical based. Other physicians in cities or treating wealthier families attended medical school, but in the 19th century, the training offered at medical schools could be completed solely by reading books, without participating in clinicals or practicums. By the early 1800s, medical schools in the United States became more prestigious but the older, more established medical schools were overseas in Europe still retained world-class reputations. Schools like the Paris Clinical School and the University of Edinburgh Medical School were around since the 18th century unlike the newly established medical schools found in Boston, New York, or Philadelphia. Very few women publicly practiced medicine. Women took care of sick family members within the home and called for the local doctor if needed, but there were very few aspects of public medicine that women practiced in the 19th century. One of the few female dominated medical fields was midwifery, in which women helped other women during childbirth.

Since women took the role of the healer within the home, one of the most common books found in the household was Every Man His Own Doctor: OR, The Poor Planter’s Physician which contained “plain and easy means for persons to cure themselves of all, or most of the distempers, incident to this climate, and with very little charge, the medicines being chiefly of the growth and production of this country”. Using the information contained in this book, many wives and mothers created herbal medicines thought to cure ailments. Herbs like lavender, rosemary, wormwood, sage, foxglove, mint, and more could help cure several ailments such as headaches, dropsy, or stomach pains. For example, the regimen listed in The Poor Planter’s Physician for fevers was to “drink freely of water gruel, orange whey, weak chamomile tea; or if his spirits be low, small wine-whey sharpened with the juice of lemon”. There were medicines such as pills, available in the 19th century, but they were unregulated, ineffective, and in many cases dangerous for people to use. Blue mass pills were commonly prescribed by doctors throughout the 19th to treat many illnesses from tuberculosis, constipation, toothache, parasitic infestations, and the pains of childbirth just to name a few. However, its main ingredient was mercury, a metallic element that is actually poisonous to consume.

At the beginning of the century, many doctors still practiced an ancient theory of medicine known as the humorous theory. This theory perpetuated the idea that when someone was ill, it was because there was an imbalance of humors (blood), yellow bile (liver), black bile (spleen), and (phlegm) and the best ways to rebalance these humors were through bleeding and purging. However, as physicians gained a greater understanding of how the human body functioned, this theory started to fall out of practice by the mid-nineteenth century, largely because of the study of anatomy made possible by autopsies.

Through the first half of the 1800s, medicine was slow to advance since it was difficult to study the human body. The idea of a “good death” and the sacredness of the body ensured that few anatomy laws were passed in the United States prior to 1860. Before the Civil War, only three anatomy laws were passed, and all but one were soon repealed. Many of these “bone bills”, including one passed in Massachusetts in 1831, allowed medical schools access to the bodies of those who died in workhouses or hospitals and who had no money for a proper burial. Yet, even with these “bone bills” loosening restrictions in some places, the growth of medical schools throughout the 19th century increased the demand. These anatomy laws did little to advance the medical field but led to an increase of grave robbing, where freshly buried bodies were stolen from graveyards and sold to medical schools. However, the availability of human remains for anatomical study changed in the 1860s with war.

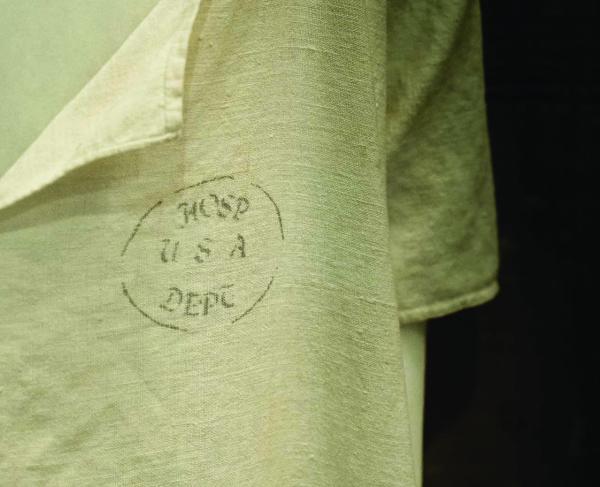

The Civil War proved to be a catalyst in advancing 19th-century medicine. The four years were marked by hundreds of thousands of cases of battle wounds, disease, infection, and death. During the first year of the war, the armies found themselves without enough surgeons, supplies, or hospitals. Lacking sufficient supplies and knowledge, both armies struggled to control the emergence of various diseases such as measles, smallpox, and typhoid. At the beginning of the war, germ theory, antiseptic practices (sterilizing instruments and wearing gloves), and effective hospital systems, were virtually nonexistent. As a result of poor sanitation, diet, ventilation, and bad hygiene disease and infection spread rampant, making disease more deadly than the battle wounds experienced on the field.

When a soldier was wounded on the field, he was brought to a field hospital where he was treated by a strained surgeon who operated on him using the same tools as all of the other soldiers before him. Equipment was rinsed in a bucket of water that was not boiled and the surgeon did not wear gloves or wash his hands with soap. After surgery, the soldier was bandaged up, sometimes with clean bandages, sometimes with materials such as curtains or bedsheets taken from nearby homes, and placed on a cot, a bed of straw, or the ground to recover. Some soldiers made a full recovery while others succumbed to their wounds due to infections such as gangrene.

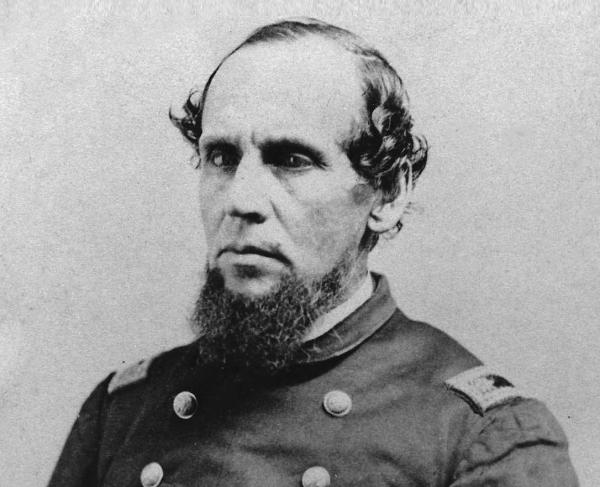

However, with hundreds of thousands of soldiers wounded, the medical field was quick to advance with new techniques that medical officers soon learned. For example, in 1862, Dr. William Alexander Hammond was appointed to Surgeon General of the United States and brought the study of anatomy and disease to the forefront of the medical department by passing Circular No. 2 and Circular No. 5

Circular No. 2 was issued on May 21, 1862, directing medical officers to “diligently collect and forward to the office of the Surgeon General all specimens of morbid anatomy, surgical or medical, which may be regarded as valuable; together with projectiles and foreign bodies removed; and such other matter as may prove of interest in the study of military medicine and surgery”. This circular, in turn, created the Army Medical Museum to house these specimens for the purpose of “illustrating the injuries and diseases that produce death or disability during war, and thus affording materials for precise methods of study or problems regarding the diminution of mortality and alleviation of suffering in armies”. Even more valuable than the unprecedented collection of specimens directed in Circular No. 2 was Circular No. 5, issued shortly after on June 9, 1862.

Circular No.5 required all physicians to write a case history with all specimens or images of interesting or unique cases sent to the museum. The circular required “all medical officers cooperate in this undertaking by forwarding to this office such sanitary, topographical, medical and surgical reports, details of cases, essays and the results of investigations and inquiries as may be of value for this work, which full credit will be given in forthcoming volumes”. This created yet another incentive for surgeons to contribute to this enormous project. Hammond later stated in a subsequent circular “that no one will neglect this opportunity of advancing the honor of service, the cause of humanity, and his own reputation”.

Both Circular No. 2 and Circular No. 5 had enormous implications on the advancement of the medical field. Not only did they create a plethora of resources available for future generations to study, but standardized the practice of diagnosing, treating, monitoring, and if necessary, performing an autopsy for study. By drafting these reports and sending specimens, medical personnel was forced to analyze the visual connection between a disease or a wound and its effects on the human body allowing for much more scientific approach to the study of medicine than ever before. These circulars led to the establishment of the Army Medical Museum and the publication of The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, which are still widely used today, not only by civilian and military doctors but historians as well, even over 150 years later. The deaths of over 600,000 soldiers over the course of the Civil War was not in vain for it allowed for the advancement of the medical field from the methods of care, germ and antiseptic theories, better procedures, medicines, and prosthetics, that allow us to live longer, healthier lives that many take for granted today.

Further Reading:

- Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion By: Joseph K. Barnes, Joseph Janvier Woodward, Charles Smart, George A. Otis, and D. L. Huntington.

- Every Man His Own Doctor: OR the Poor Planter’s Physician: A Treatise on the Prevention and Cure of Diseases By: William Buchan

- Learning from the Wounded: The Civil War and the Rise of American Medical Science By: Shauna Devine

- The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine By: Glenna R. Schroeder-Lein