Nearly half of the Medals of Honor that have been distributed since the award’s inception in 1862 were bestowed for actions during the Civil War. A great deal is known about some of the events for which those men — and, in only one case, a woman — were recognized. But for all that has been written about the battle exploits of those brave men, their broader lives are often shrouded in obscurity.

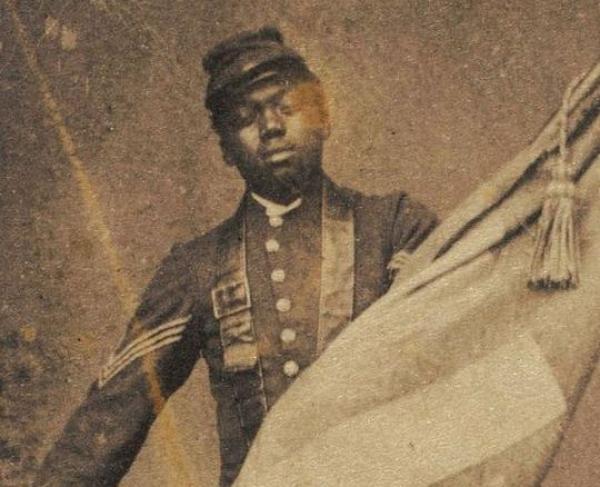

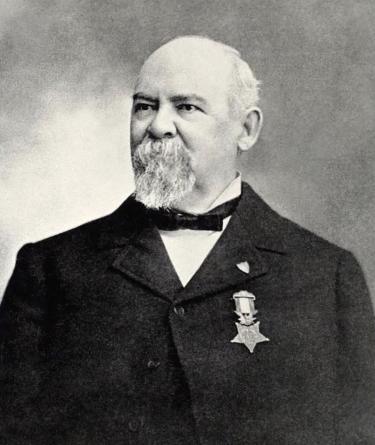

William Harvey Carney

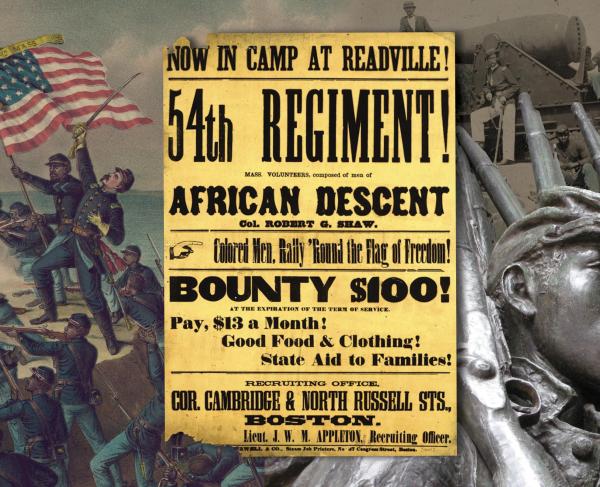

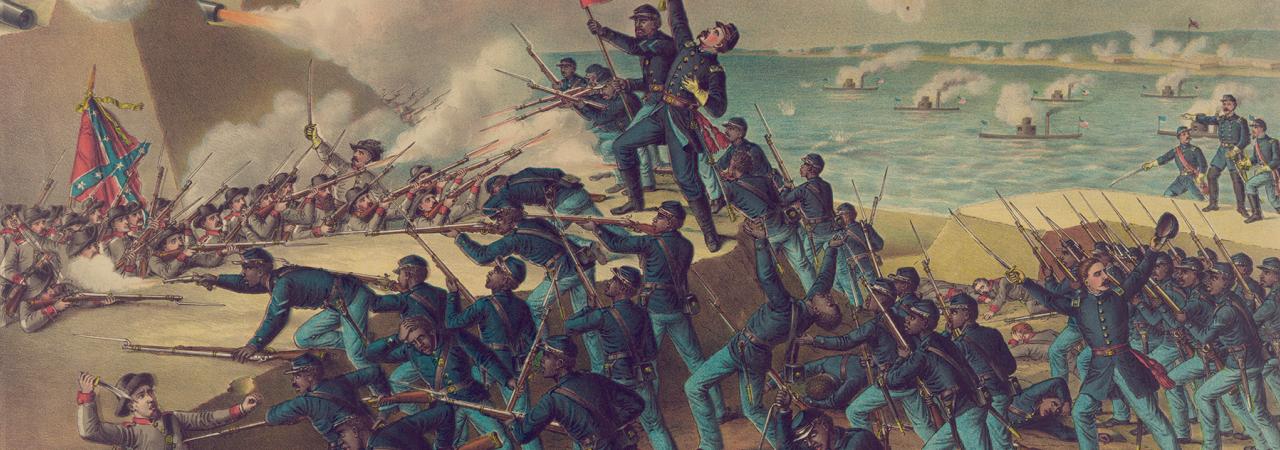

William Harvey Carney, one of the heroes of the 54th Massachusetts’s attack on Battery Wagner was born into slavery in Norfolk, Va., escaping via the Underground and building a life in the Bay State. He left his studies for the ministry to enlist in the first African American regiment raised by the state as a sergeant, and marched off to war down Beacon Street on May 28, 1863, an event immortalized in the bronze Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s memorial on Boston Common.

The experience of Carney’s regiment was fictionalized and depicted in the 1989 film Glory, familiarizing many Americans with this dramatic engagement. Carney himself is not directly portrayed in the film, although his own experience in the engagement was suitably dramatic. When he watched the color bearer fall, fatally wounded, Carney took up the flag and carried it for the rest of the battle. He briefly planted it atop the parapets and brought it safely back to Union lines in retreat. In the process he was shot in the head, chest, legs and one arm. Despite this, he refused offers from men of other units to take the flag so he could receive medical aid, replying "No one but a member of the 54th should carry the colors!”

Born into slavery in the Norfolk area of Virginia, William Carney escaped servitude as a young man on the Underground Railroad to join the rest of his...

The severity of his wounds meant Carney was discharged from the army in 1864. Like many Civil War veterans, Carney waited several decades to receive his Medal of Honor, which was issued on May 23, 1900. In the intervening years, he had returned to his home in New Bedford and taken a position caring for the city’s streetlights. He went, briefly, to California, but returned to the maritime city permanently in 1869 and began a 32-year career as a letter carrier. He married and raised a daughter in a home on Mill Street that now resides on the National Register of Historic Places. William Carney died in December 1908 following an elevator accident in the Massachusetts State House, where he worked as a messenger on behalf of the Department of State. He is buried in Oak Grove Cemetery.

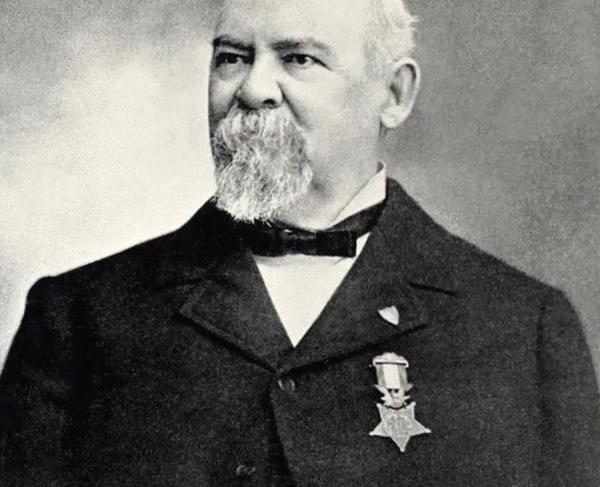

George H. Maynard

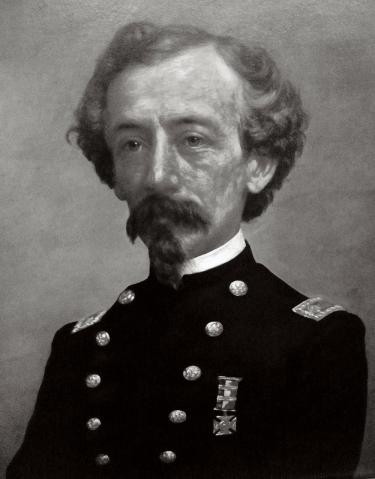

George H. Maynard was born in Waltham, Mass., in February 1836. After attending public schools in that Boston suburb, he became apprenticed to a jeweler and watchmaker at age 15. On July 20, 1861, he enlisted as a private in Company D of the 13th Massachusetts Infantry, which was posted on patrol of the Upper Potomac until March 1862. The unit fought at Cedar Mountain and Second Manassas, where it lost 193 men, including 19 killed. At Antietam, the 13th suffered nearly 140 casualties in less than two hours of fighting in the Cornfield.

In preparation for the Battle of Fredericksburg, the 13th Massachusetts crossed the Rappahannock River at the lower crossing early on the morning of December 12, 1863. Placed as skirmishers, theirs was among the first units to advance past the Richmond Stage Road the following day, engaging the Confederates on the Slaughter Pen Farm. Once the division’s main line of advance surpassed the 13th’s position, it retired to the rear for more ammunition.

Upon reaching safety, Maynard realized that his comrade Charles Armstrong was not with the unit. Of his own volition, Maynard chose to return to the active battlefield in search of Armstrong. Under enemy fire, he located his friend and successfully removed him to a Union field hospital, where Armstrong ultimately succumbed to his serious wounds.

Maynard was mustered out of service with the 13th in February 1863. Just over a year later, he received a commission as a captain in the 82nd United States Colored Infantry, which participated in the siege and battle of Fort Blakely, Ala. In March 1865, Maynard was breveted to the rank of major in recognition of his meritorious service throughout the war. He left military service permanently in September 1866.

Returning to Boston, Maynard married Harriet Henry, with whom he had seven children, only two of whom lived to adulthood. He became an active member of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts, the oldest chartered military organization in America, as well as the freemasons of the York Right. On March 20, 1898, he received the Medal of Honor for his actions at the Battle of Fredericksburg. He passed away in 1927 at the age of 91 and was buried in Waltham, alongside his wife and children, all of whom had preceded him in death.Maynard’s Medal of Honor and his Civil War uniform are displayed at Faneuil Hall in Boston, part of the museum of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company, alongside an oil painting depicting his heroic act at Fredericksburg. Each year, members of the company don their uniform blazers bearing the group’s motto Facta, Non Verba — “Deeds, not words” — hold a ceremonial wreath-laying at his grave.

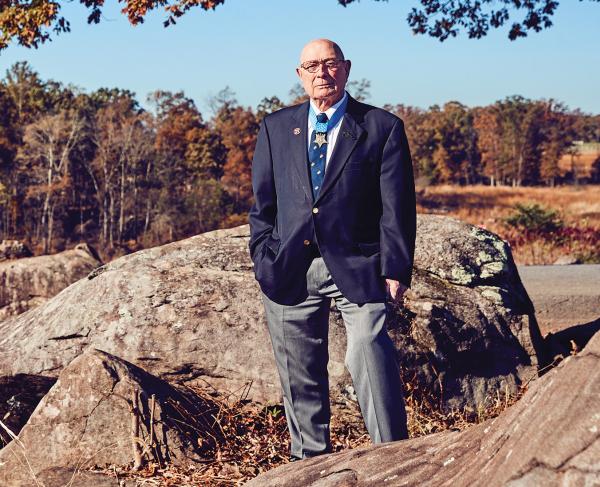

George W. Mears and the “Mears Party”

Recognizing the heroism exhibited by the so-called Mears Party is complicated by a number of factors. The paucity of details in the relevant Medal of Honor citations is compounded by misidentification of the location where the event occurred. The six relevant citations vary in their details; four place their charge as “near Devil’s Den,” as opposed to its true location within the Valley of Death, while the others offer no detail as to location. National Park Service historian Jim Heiser has made significant study of this action, sharing his research in a two-part post at On the Fields of Gettysburg, the blog of Gettysburg National Military Park. (see Part 1 and Part 2 of his research)

But for a time, an even greater and more fundamental mystery surrounded the charge which had dislodged Confederate sharpshooters threatening the flank of the Pennsylvania Reserves during their advance: Just who had made the charge?

When the veterans gathered at Gettysburg in the 1890s to dedicate their unit memorials, reminiscences naturally turned to that event, which had been the most dramatic moment of their involvement, although it was only a footnote in most narratives of the full battle. Without question, Sgt. George Mears — who had later lost his left arm at New Hope Church, Va. — had displayed incredible courage by gather a handful of volunteers around him. In August 1896, 40 regimental alumni signed a petition sent to the Secretary of War nominating Mears for consideration to receive the Medal of Honor. With compelling testimony of eyewitnesses who believed Mears’s actions had save their own lives, the recognition was quickly approved.

It was certain that Mears was not the only man to deserve credit for that action, but not even he could remember all of those who charged alongside him. ““The squad was so quickly formed, the men not counted or their names taken down and I venture none were then thinking of medals of honor. The thing was done with such a rush, names or the number of men were not thought of,” he testified. “The squad was disbanded as hurriedly as it was called together each returning to his company and place in line of battle, which was then raging. The thing was so quickly done that some of the men on the left of the Regt. did not know of the incident.”

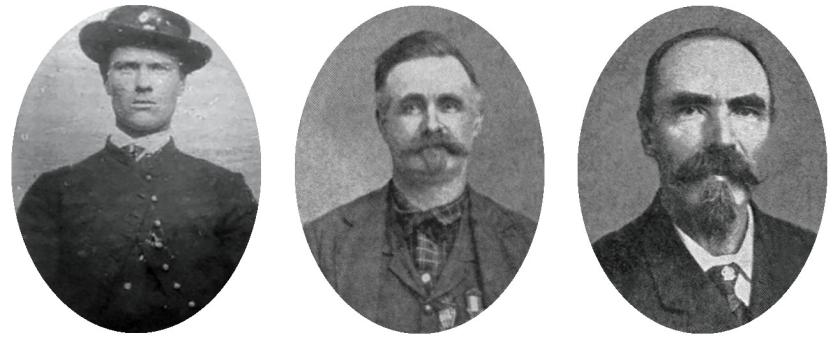

Three of those who accompanied the charge were recalled in short order by Mears and other officers present that day — Chester Furman, John Hart and J. Levi Roush — and all three received their own Medals of Honor within about six months of Mears. There was general consensus that two more men were involved, but their identities were harder to pin down. Three years later, Wallace Johnson stepped forward to acknowledge his part in events, but the final participant was still a mystery.

In the years after the war, Thaddeus Smith left Pennsylvania and headed west, settling in Port Townsend, Wash., a distance that made it difficult for him to play a role in the active veterans organization of the Pennsylvania Reserves. Upon eventually realizing that his comrades had been honored for their involvement, Smith reached out to those who had been involved in the recognition process, confessing, “I had thought that as I had not received a ‘Medal’ when the rest did that I had been forgotton (sic), but the truth is the boys did not know where I was and I did not appreciate the fact that I have been out of the state since 1869.”

Having survived a bayonet charge into a sharpshooters’ den, the members of the Mears Party remained lucky in life; the first, Roush, did not die until 1906. German immigrant Hart passed the following year, Furman in 1910 and Johnson in 1911. Mears passed in 1921 and is buried in the same Bloomsburg, Pa., cemetery as Furman. Smith, firmly settled on the West Coast, survived until 1933.

Related Battles

23,049

28,063

1,515

174

12,500

6,000