Joseph Plumb Martin: Voice of the Common American Soldier

Unlike in the years after the Civil War, when soldiers by the thousands published their wartime memoirs, soldiers who fought during the War for Independence rarely published their personal narratives. However, one did and his memoir, published in 1830, is considered a classic as well as a useful tool for historians in understanding the life of the common soldier in the Continental Army. At the age of 70, Joseph Plumb Martin took up the pen and wrote A Narrative of Some of the Adventures, Dangers, and Sufferings of a Revolutionary Soldier, Interspersed with Anecdotes of Incidents that Occurred Within His Own Observations. The book never gained a wide readership at the time and Martin died twenty years later. His story was lost to the dustbin of history.

The book was rediscovered more than a century later, and it was republished in 1962 as Private Yankee Doodle. Like many memoirs, it cannot be taken at face value, and some historians believe that Martin embellished his tale by adding fanciful descriptions of various actions. However, many Revolutionary War re-enactors consider it a crucial primary source from which to draw inspiration in order to perform effective first person interpretation of the average soldier in Washington’s Army. Also setting Martin’s history of the war apart from other accounts is that it is a narrative from someone in the ranks. Readers freeze with Martin at Valley Forge and they share his other privations. Hunger was a constant companion. This is not a heroic account of the war by one of its icons, like Washington, Knox, or Greene. Martin’s heroism is rooted in the experience endured by the common soldier, the backbone of the American Continental Army. “Suffering” is a not-so-quiet theme of Martin’s narrative.

When Martin first entered the war at age 15, he was a Private. By the time the war concluded at Yorktown in 1781, he had risen to the rank of Sergeant in the Continental Army. He was 22 and he had grown up quick in army life.

Born in Western Massachusetts but raised principally by his grandparents in Connecticut, Martin was itching to serve the colonial cause when fighting erupted at Lexington and Concord. Like any rambunctious teenager, he wanted to get into the fight. When his grandparents refused him permission to enlist, he threatened to run away and join up with American maritime privateers waging war on the high seas against the British Navy. Reluctantly, his grandparents gave in, and soon Martin found himself a member of the Connecticut State Troops in 1776. Martin saw action during the lopsided British victory on Long Island in August of that year and continued his first tour of duty, seeing combat throughout the subsequent New York Campaign at Harlem Heights and White Plains. He returned home in early winter 1776.

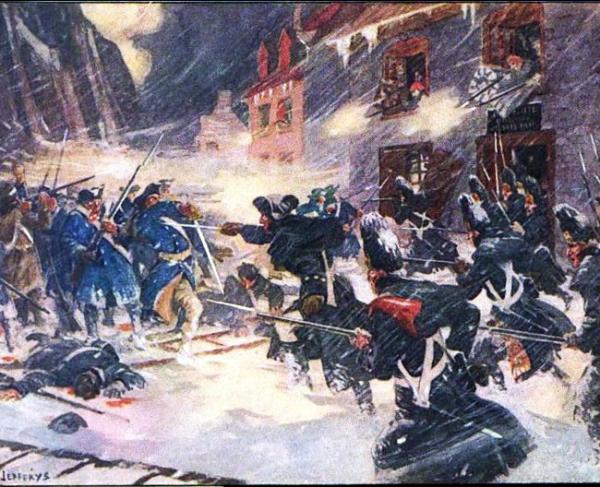

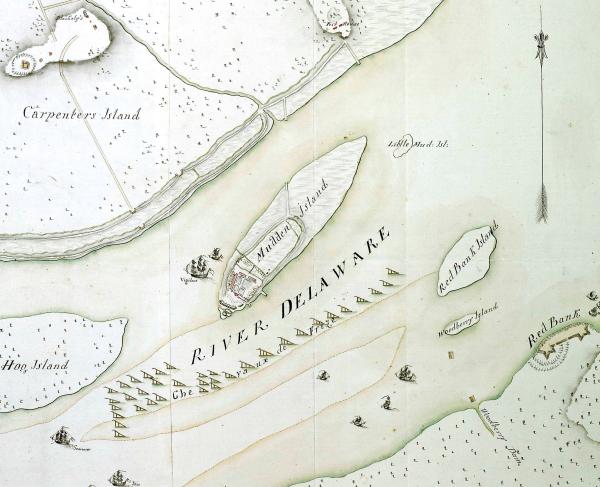

Boredom caught up with him while back in Connecticut and he reenlisted in April 1777, this time planning to stick it out for the duration of the war as a member of the 8th Connecticut Regiment, also known as the 17th Continental Regiment. During the remainder of his service he saw action at Germantown and the siege of Fort Mifflin, endured the encampments of Valley Forge and Morristown, fought at the Battle of Monmouth and participated in the Siege of Yorktown, witnessing at the end of that campaign the surrender of Cornwallis's army.

By the time he reached Yorktown he had been promoted to Sergeant and was attached to a unit of sappers who first dug Washington’s parallel of entrenchments placing Cornwallis’ army under siege and then cleared the way for the Continental Army to assault British Redoubt Number 10, which forced the British hand. His account of the assault on Redoubt Number 10 is compelling as it is insightful:

“At dark the detachment was formed and advanced beyond the trenches and lay down on the ground to await the signal for advancing to the attack, which was to be three shells from a certain battery near where we were lying. All the batteries in our line were silent, and we lay anxiously waiting for the signal. The two brilliant planets, Jupiter and Venus, were in close contact in the western hemisphere, the same direction that the signal was to be made in. When I happened to cast my eyes to that quarter, which was often, and I caught a glance of them, I was ready to spring on my feet, thinking they were the signal for starting. Our watchword was “Rochambeau,” the commander of the French forces' name, a good watchword, for being pronounced Ro-sham-bow, it sounded, when pronounced quick, like rush-on-boys.

“We had not lain here long before the expected signal was given, for us and the French, who were to storm the other redoubt, by the three shells with their fiery trains mounting the air in quick succession. The word up, up, was then reiterated through the detachment. We immediately moved silently on toward the redoubt we were to attack, with unloaded muskets. Just as we arrived at the abatis, the enemy discovered us and directly opened a sharp fire upon us. We were now at a place where many of our large shells had burst in the ground, making holes sufficient to bury an ox in. The men, having their eyes fixed upon what was transacting before them, were every now and then falling into these holes. I thought the British were killing us off at a great rate. At length, one of the holes happening to pick me up, I found out the mystery of the huge slaughter.

“As soon as the firing began, our people began to cry, “The fort’s our own!” and it was “Rush on boys.” The Sappers and Miners soon cleared a passage for the infantry, who entered it rapidly. Our Miners were ordered not to enter the fort, but there was no stopping them. “We will go,” said they. “Then go to the d ——— ,” said the commanding officer of our corps, “if you will.” I could not pass at the entrance we had made, it was so crowded. I therefore forced a passage at a place where I saw our shot had cut away some of the abatis; several others entered at the same place. While passing, a man at my side received a ball in his head and fell under my feet, crying out bitterly. While crossing the trench, the enemy threw hand grenades (small shells) into it. They were so thick that I at first thought them cartridge papers on fire, but was soon undeceived by their cracking. As I mounted the breastwork, I met an old associate hitching himself down into the trench. I knew him by the light of the enemy’s musketry, it was so vivid. The fort was taken and all quiet in a very short time. Immediately after the firing ceased, I went out to see what had become of my wounded friend and the other that fell in the passage. They were both dead. In the heat of the action I saw a British soldier jump over the walls of the fort next the river and go down the bank, which was almost perpendicular and twenty or thirty feet high. When he came to the beach he made off for the town, and if he did not make good use of his legs I never saw a man that did.”

After Yorktown, Martin accompanied Washington’s Army back to New York and he left the service when the British evacuated New York and the Continental Army mustered out.

For a while he taught school in New York, but eventually settled in Maine where he got married in 1794 to Lucy Clewley. That same year he became embroiled in a testy land dispute with former Continental Army Chief of Artillery Henry Knox. Martin lost the dispute and as a result lost land. A personal appeal to Knox fell on deaf ears. Together with his wife, he eked out an existence farming on the little parcel of land that remained his and had five children.

Like many Continental Army veterans, Martin repeatedly struggled to receive a pension, which had been promised by Congress. His was finally approved in 1818 and for the rest of his life he received $96 a year for payment of his service to the new nation. His idea to write his memoir may have been driven in part to secure additional financial support. By the time he was granted his pension, he was destitute and penniless. Visitors to Valley Forge National Historical Park can stroll the perimeter of Washington’s famous encampment site by walking the Joseph Plumb Martin Trail.

Related Battles

217

233

1,111

533

325

381

389

8,589

2,000

388