The French and Indian War (1754-1763): Causes and Outbreak

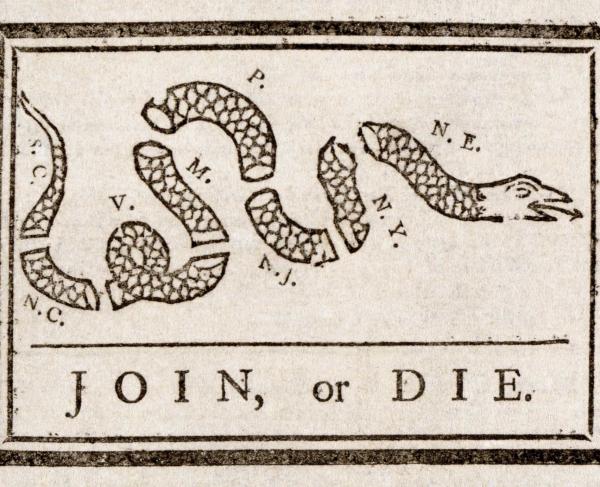

The French and Indian War is one of the most significant, yet widely forgotten, events in American history. It was a conflict that pitted two of history’s greatest empires, Great Britain and France, against each other for control of the North American continent. Swept up in the struggle were the inhabitants of New France, the British colonists, the Native Americans, and regular troops from France and Britain. While the major fighting occurred in New York, Pennsylvania, Canada, and Nova Scotia, the conflict had far greater implications overseas and ignited the Seven Years’ War worldwide.

Since the late 17th century, hostilities between France and Great Britain in North America had been continuous. Three major conflicts—King William’s War (1689-1697), Queen Anne’s War (1702-1713), and King George’s War (1744-1748)—had all begun in Europe and made their way to the colonies. The French and Indian War is unique, because the fighting began in North America and spread to the rest of the world. In western Pennsylvania, the order to fire the first shots of the conflict were given by none other than a young officer from Virginia named George Washington. Many men, both American and British, who would serve in the Revolutionary War found themselves engulfed in the struggle.

What was it that both sides wanted to obtain during the French and Indian War? The answer is the same as for most wars for empire—economical and territorial expansion, and to project influence over new lands and peoples.

By the 1750s, the population of Britain’s colonies in North America was over 1 million. Its inhabitants were concentrated along the eastern seaboard from Maine (Massachusetts) to Georgia, and in Nova Scotia, which was ceded to Britain following the War of Spanish Succession. Because the Atlantic Ocean rested to the east of the colonies, there was only one direction to expand—westward. As for the French, the colony of New France numbered just over 60,000, and its territorial holdings stretched in a large arc from the Gulf of the Saint Lawrence River, through the Great Lakes, and down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico. The majority of settlers occupied Canada, but forts and outposts kept communications open along the waterways leading down to Louisiana. With the French to the west and the Spanish in Florida, the British colonists were boxed in. Stuck in the middle were the Native Americans, and many of them, like the Iroquois, were effective in commercially pitting Britain and France against each other all the while remaining a “neutral” nation.

New France, whose economy revolved around the fur trade, was not at all a lucrative colony for King Louis XV. That did not, however, stop France from working to prevent Britain from expanding its empire in North America. The area of contention that would ultimately serve as the spark to ignite the powder keg of war was a 200,000 square mile region known as the Ohio River Valley.

The Ohio River begins its journey at present-day Pittsburgh, where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers converge with it, creating what is known as the “Forks,” and eventually empties into the Mississippi River in Illinois. This waterway was crucial for France to maintain possession of in order to keep open its line of communication with its military outposts and settlements to the south. By the late 1740s, a recent uptick in British traders moving through the region to do business with the Native Americans put New France on high alert. It was only a matter of time before Britain, who saw the Forks of the Ohio as part of the King’s dominion, sent a military force from Pennsylvania or Virginia to assert its dominance in the region.

In response to the threat of British encroachment in the Ohio River Valley, in June 1749, the governor of New France dispatched a small force of over 200 men to travel through the region to reaffirm French claims and reestablish His Most Christian Majesty’s authority over the Native Americans, who were keener on trading with the British. Along the way, the French commander, Captain Pierre-Joseph Céloron de Blainville, buried multiple lead plates inscribed with words which claimed the valley and its waterways for Louis XV. In the end, the mission was anything but a success. It was clear that the Native Americans were not solely devoted to the French any longer.

In 1747, the Ohio Company was founded to open trade into the Ohio River Valley and further expand Virginia westward. As Britain’s continued interest in the region grew, France began constructing forts below the Great Lakes with the intention of securing the Forks. The British colonies beat them there. In the spring of 1754, Virginia troops reached the confluence and began constructing a fortification. However, a larger Canadian force arrived and the Virginians abandoned the site. Subsequently, the French built Fort Duquesne. Now it was Britain’s turn to respond.

Arriving in the Ohio Country a month after the French occupied the Forks were over 100 men under the command of 22 year old Lieutenant Colonel George Washington of Virginia. They encamped 50 miles to the east of the Forks in an open field known as Great Meadows. Dispatched from Fort Duquesne and heading in their direction was a small French party led by Ensign Joseph Coulon de Jumonville with orders to obtain intelligence on the British force and if possible, demand them to leave. Washington responded to the news of the French movement and led a force of his own to intercept them. With 40 Virginians and roughly a dozen Iroquois allies, Washington ambushed Jumonville not far from Great Meadows. These were the first shots fired during the French and Indian War and would have global ramifications. The skirmish left Jumonville and nine of his men dead, as well as twenty-one others wounded. A survivor made his way back to Fort Duquesne and reported to his superiors what had happened.

Washington returned to Great Meadows and constructed a crude palisade named Fort Necessity. On July 3, a force of over 300 Canadians and Native Americans led by Jumonville’s brother surrounded and attacked Washington. The Virginian was forced to capitulate and, through poor translating, signed a document admitting to the “assassination” of Ensign Jumonville. After receiving the news of the loss of the Ohio River Valley, London reacted. The following year, British regular regiments were on their way across the Atlantic.

On February 19, 1755, newly-appointed Major General Edward Braddock, Commander-in-Chief of His Majesty’s Forces in North America, arrived in Hampton Roads, Virginia. The British were now poised to outmaneuver the French and capture territories in New York, Nova Scotia, and the Ohio River Valley before a formal declaration of war could be made between both countries. Braddock, with orders in hand from Britain’s Captain-General, William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, had just the plan to do so.

In the middle of April, the general met in Alexandria with the royal governors of Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia to discuss a four-pronged offensive that summer to oust the French from His Majesty’s North American dominion. Armies consisting of regular troops, colonial provincials, and Native American auxiliaries were assembled, and that summer Britain made its mighty thrust to reclaim the continent.

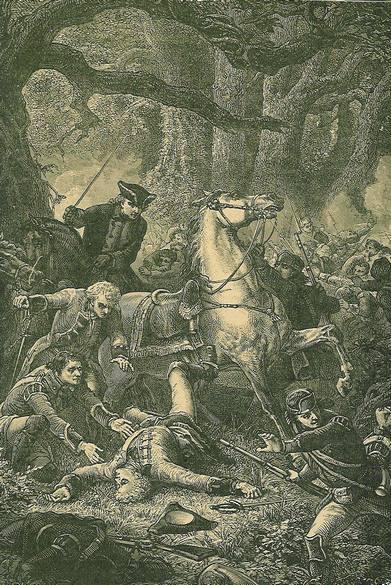

No war had officially been declared by Britain or France, but fighting raged in Nova Scotia, Upstate New York, and Western Pennsylvania. A British force succeeded in capturing two forts in Acadia, thus ousting French influence from the region. At the southern shore of Lake George in New York, an entirely colonial force threw back repeated assaults by professional French troops and prevented the crucial waterway from falling into enemy hands. These two victories were offset, however, by one of the most disastrous defeats in British military history. On July 9, 1755, less than ten miles outside of Fort Duquesne, a force of 1,500 regulars and provincials led by General Braddock was slaughtered at the Battle of the Monongahela. Over 900 men fell killed, wounded, or captured to the French, including Braddock, who succumbed to his wounds several days later. The British expedition that summer against Fort Niagara along Lake Ontario failed to materialize and was called off. French presence remained in the Ohio River Valley, Great Lakes, and along Lake Champlain.

Seventeen fifty-five was a disaster for British arms in North America that drew the opposing battle lines for the coming years. Blood had been spilled in an undeclared war on the continent that would ignite a world war the following spring.

Further Reading:

- Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754 - 1766 By: Fred Anderson

- Bloody Mohawk: The French and Indian War & American Revolution on New York's Frontier By: Richard J. Berleth

- The French and Indian War: Deciding the Fate of North America By: Walter R. Borneman

- A Few Acres Of Snow: The Saga Of The French And Indian Wars By: Robert Leckie

- Braddock's Defeat: The Battle of the Monongahela and the Road to Revolution By: David Preston