Patrick Henry

Patrick Henry’s legacy has become indelibly linked with his oration to the Second Virginia Convention where he proclaimed, “Give me liberty or give me death.” However, Henry did not just give one speech and was not merely an unwavering patriot, Henry was a skilled politician, lawyer, and orator and his life and opinions did not always line up with other founders.

The orator was born in Studley in the Colony of Virginia on May 29, 1736. Patrick Henry’s father, John Henry, was an educated Scottish immigrant who had married into the considerable fortune of Sarah Winston Syme, a wealthy widow with a good family name. Henry did not attend a university; instead, his father tutored him. His mother provided him with his oratorical and religious education by bringing him along to numerous Presbyterian speakers across the colony. These speakers were products of the Great Awakening and as a result they had a unique oratorical style, speaking in the people’s language and to their hearts rather than their logic. Henry adapted this style of oration to the political sphere throughout his life. In 1754, the young patriot married Sarah Shelton; and as a dowry, her father gave the young couple 300 acres of land and six slaves. However, years of drought killed Henry’s hopes of being a prosperous planter, and he moved in with his father-in-law at Hanover Tavern. Henry became the de-facto manager of the tavern—serving drinks, entertaining guests with his fiddle, and meeting with travelers passing through Hanover. During Henry’s tenure at the Hanover Tavern, he and Thomas Jefferson became close friends.

While working at the tavern, Henry began to pursue a career in law. After only one month of studying, he applied for a lawyer’s license in Williamsburg and shortly thereafter opened a practice. Henry used his position as a lawyer to fight for what he believed were natural rights. After the crown repealed the Twin Penny Acts in 1763, Virginia policy changing debts based on the price of tobacco, Henry took a specific case and filibustered the trial arguing that the Act was unconstitutional and therefore the king had lost his right to rule. Henry won the case and became a hero to Virginia, gaining 164 new clients that year.

After his defense of Virginia, Henry became a backwoods Virginia hero. In 1765 he won a seat on the Virginia House of Burgesses. The moment Henry was elected, he was forced to travel to Williamsburg, as the Burgesses were already in session. When he arrived, the Burgesses were debating the Stamp Act, instructing their contacts in London to oppose the bill. When the Act passed, the burgeoning politician introduced the Stamp Act Resolves. The “Resolves” established that Virginian colonists had the same rights as British citizens and that taxation without representation is tyranny. During this session, Henry also gave an impassioned speech arguing against the Stamp Act. During the speech, the not so tactful orator carefully referenced how tyrants were murdered, never actually mentioning King George; however, the room read his tone, and many decried his statement as treason. Henry famously replied, “If this be treason, make the most of it.”

When he was not attending the House of Burgesses, Henry greatly expanded his wealth and stature through land speculation and his law practice. During this time, he amassed enough wealth to buy land and slaves. It is essential to note the contradiction in Henry’s views and actions on slavery. Henry argued against slavery throughout his life, but from his purchase of land to his death, he continued to purchase and sell slaves. Henry and Jefferson are parallels in that they advocated for ending the trans-Atlantic slave trade, believing it would eventually end slavery, while at the same time engaging in the practices that made American slavery expand across the south, even after the end of the trans-Atlantic trade.

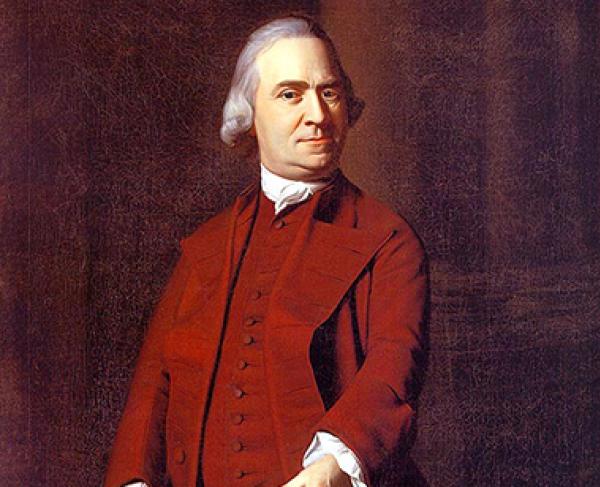

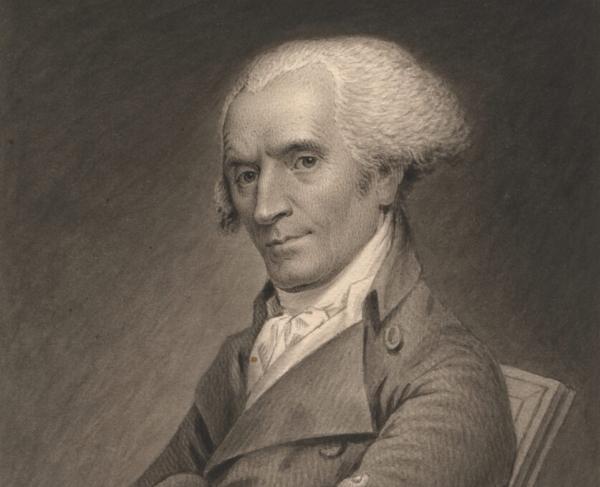

Henry attended the Virginia Conventions from 1774-1776; these meetings set out a plan for the colony of Virginia and were crucial for the nation’s independence. Utilizing committees of correspondence, the rising Virginian contacted John and Samuel Adams, and together they decided to push their respective colonies to independence. Henry’s defining moment came in the Second Virginia Convention—when he delivered his now famous “Give me Liberty or give me death!” speech. Many future patriots were in the audience, including Thomas Jefferson and George Washington. The address helped drive prominent Virginians to prepare for war. No one in the audience recorded the speech, and later historians pieced the speech together, it is unclear if Henry actually concluded with the famous quote or if that was invented years later to sell books.

Henry had a very short stint in the military during the War for Independence. British officials had seized gunpowder in Williamsburg; Henry returned from his journey north to the Second Continental Congress to lead the Virginia militia against the British. Henry likely had enough men to take Williamsburg and defeat the British. However, many colonial messengers persuaded the politician turned militia leader to be cautious, so he gave up the military action and instead negotiated payment for the gunpowder. Henry played a small role in the Continental Congress before returning to the Virginia militia. At one point he was placed in charge of all Virginia forces. Until the armies were reorganized under continental control and Henry was to be placed under a man, he previously outranked, obviously slighted, he resigned his position. He never saw action during the war and returned to Virginia.

The former commander returned to his old post at the Fifth Virginia Convention. During this Convention, he produced a resolution urging all colonies to seek independence. The resolution was unanimously passed, and the Convention sent a copy to Thomas Jefferson in Philadelphia, it specifically instructed Jefferson to seek independence. The resolution must have helped, as it was Jefferson who would pen the Declaration of Independence. Henry helped to construct the state constitution and on June 29, 1776, the Convention elected him the first governor of independent Virginia. The governor used his power during the war to help his friend George Washington, recruiting troops for the cause and sending supplies to Valley Forge during the infamous winter. Henry served three consecutive terms, the maximum amount allowed by the Virginia constitution and returned to his home in Leatherwood. He continued to work in the government helping on the county court and advising the new governor of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson. He was offered to be elected a delegate to Congress but declined due to health issues.

Henry was re-elected governor in 1785, although this term was much less eventful than his first term. He notably stopped some citizens in southern Virginia from attempting to create a new state with parts of North Carolina. After his second term as governor, he continued to be active politically, notably in his opposition to the Constitution. Though he did not serve at the Constitutional Convention, he was offered a place at the Convention but refused, Henry fought hard against the proposed United States Constitution. George Washington brought a copy of the Constitution to Henry urging him to support it at the Virginia Ratifying Convention. However, Henry opposed the strong executive the Constitution created and decided to fight against its ratification. This disagreement caused a rift between the longtime allies Washington and Henry. Henry was sick for most of the Convention and knew the Constitution would pass but still fought for what he believed. The orator’s speeches filled one-quarter of the Convention’s debates. During this time, he helped to pen the Anti-Federalist Papers, the now largely forgotten response to the Federalist Papers. Though Henry’s fight against the Constitution was ill-fated and often criticized by his contemporaries, Henry never rejected the Constitution after it passed and his critiques in the Anti-Federalist Papers influenced the Bill of Rights and Democratic-Republican policy.

After leaving governance entirely in 1790, Henry returned to law, mainly to pay off debts he incurred during his time as governor. He reconciled with George Washington, despite being on different sides of the political spectrum during the passage of the Constitution, he found himself more aligned with Federalists only three years later. Washington even offered him multiple prominent positions in his administration: a seat on the Supreme Court, the position of Secretary of State, and Minister to Spain, but he refused every time, instead choosing to stay with his family. In 1796 many influential Virginians tried to push for him to make a run for president, but still, Henry refused. Henry forever became associated with Cincinnatus, returning to his plow, resisting power.

Henry died on June 6, 1799, of stomach cancer. Every Virginia paper devoted long sections lamenting his loss and the impact he had on American and Virginian society. He may only be known for one speech, but that speech represents a lifetime of work in the pursuit of liberty.